California was the only U.S. jurisdiction that had no version of American Bar Association Rule 8.3, which reads in part, “A lawyer who knows that another lawyer has committed a violation of the Rules of Professional Conduct that raises a substantial question as to that lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer in other respects, shall inform the appropriate professional authority.”

“Shall” means must, and thus, theoretically, a lawyer who does not report a lawyer for misconduct that amounts to a serious legal ethics violation is himself or herself committing such a violation as well. That’s the theory.

The California legal community has just gone through a spectacular scandal. Tom Girardi, a famous and much-acclaimed plaintiffs trial lawyer, was disbarred after it was discovered that he had defrauded many clients and illegally obtained millions of dollars in the process. The California bar’s investigation report was horrific: his corrupt activities were successful for so long in part because he recruited—and bribed—members of the State Bar leadership and the organization’s employees. Over a hundred lawsuits had been filed against Girardi by clients for misappropriation of funds, but his record with the Bar remained pristine.

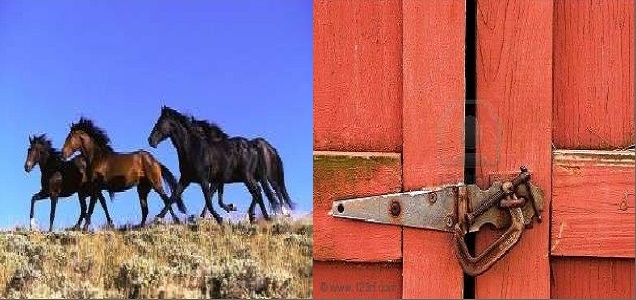

Shortly after the ugly story broke, California began to take steps to add some form of 8.3 to its Rules of Professional Conduct governing the ethics of its members, a cynical and useless move designed to appear responsible. It was also an example of what Ethics Alarms calls “The Barn Door Fallacy,” a phenomenon most common today in the area of post-tragedy gun legislation. After a high-profile disaster, the response is to “do something” that supposedly would have prevented the disaster if it had been in place earlier. Usually, as in this case, the reality is that it would not.

Rule 8.3 is something of an illusion anyway. Bar associations are reluctant to second guess a member and punish him or her for their personal assessments of what kind of conduct constitutes “raising a substantial question as to that lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer in other respects.” Stealing money from a client is definitely in that category, but proving that another lawyer “knows” about such conduct as opposed to “suspecting” it is not easy. Most bar counsel have no stomach for it, and prosecutions are absurdly rare.

The fact that 8.3 is called the “Snitch Rule” in the profession tells you how most lawyers feel about it. In general, lawyers tend to make ethics complaints to their bars about adversaries. Blowing the whistle on one’s own firm member, a powerful partner, a close colleague or a friend is rarer than—well, pick your metaphor, I’m not feeling clever today.

To see how the news out of California is even less than meets the eye, note how the state’s version of 8.3 is narrower than any other state. It reads,

a. A lawyer shall inform the State Bar when the lawyer has personal knowledge that another lawyer has committed a criminal act that reflects adversely on the lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness, or fitness as a lawyer in other respects as prohibited by rule 8.4(b).

b. For purposes of this rule, “personal knowledge” is distinct from the definition of “[k]nowingly,” “known,” or “knows” under rule 1.0.1(f) and is limited to information based on firsthand observation gained through the lawyer’s own senses.

The California Bar and the news media have headlined this development, “New California Rule Compels Attorneys to Report Misconduct by Other Attorneys.” As you can see from the text of the rule, that’s deceitful and misleading. It only “compels” lawyer to report crimes: the rest of the nation’s lawyers are supposed to report serious ethics violations, most of which are not crimes. As officers of the court (as well as good citizens) lawyers were already obligated to report crimes “based on firsthand observation gained through the lawyer’s own senses.”

I have sought advisory opinions on this rule a few times to see if I needed to report a lawyer.

It came down to what you said, was the conduct bad enough to call into question the person’s ability to practice. I always concluded that it was not.

For instance, one time, a lawyer contacted my client even though I represented the person. That can be a serious ethical breach but, in my case, the lawyer had just hit “Reply All” on an e-mail I had sent (and copied my client on). While this was technically a violation of the rule, it was more a matter of oversight and inadvertence. (I have done it myself on occasion; one of the hazards of technology and the ease of communication.). It is a mistake that is easily correctable by being mindful and does not really reflect on fitness. And, to the extent that the disciplinary process is not for the purpose of punishment, but to protect the public and foster adherence to the ethics rules, a complaint about such conduct would likely not fulfill the purpose of the rules.

In another instance, I did report a lawyer whom I believe revealed confidential information of a client in order to impeach her in a hearing. Under the California rule, I would not have been required to make that complaint because: a) the conduct was not criminal; and b) I had no firsthand knowledge of the revelation of confidential information; I just had a very strong suspicion.

-Jut