2024 was a bad year for the New York Times’s ethics advice columnist, Kwame Anthony Appiah. “He”The Ethicist” showed unseemly sympathy for the Trump Deranged all year, and not of the “You poor SOB! Get help!” variety, but more frequently of the “You make a good point!” sort, as in “I can see why you might want to cut off your mother for wanting to vote for Trump!” I was interested to see if the inevitability of Trump’s return might swerve Prof Appiah back to more useful commentary on more valid inquiries. So far, the results in 2025 have been mixed.

This week, for example, Appiah thought this silly question was worth considering (It isn’t):

“I am going to tell a brief story about my friend at his funeral. The incident happened 65 years ago. The problem is that I am unsure whether the details of the story, as I remember them, are factual or just in my imagination. No one who was a witness at the time is still living. Should I make this story delightful and not worry about the facts, or make the story short, truthful and perhaps dull?“

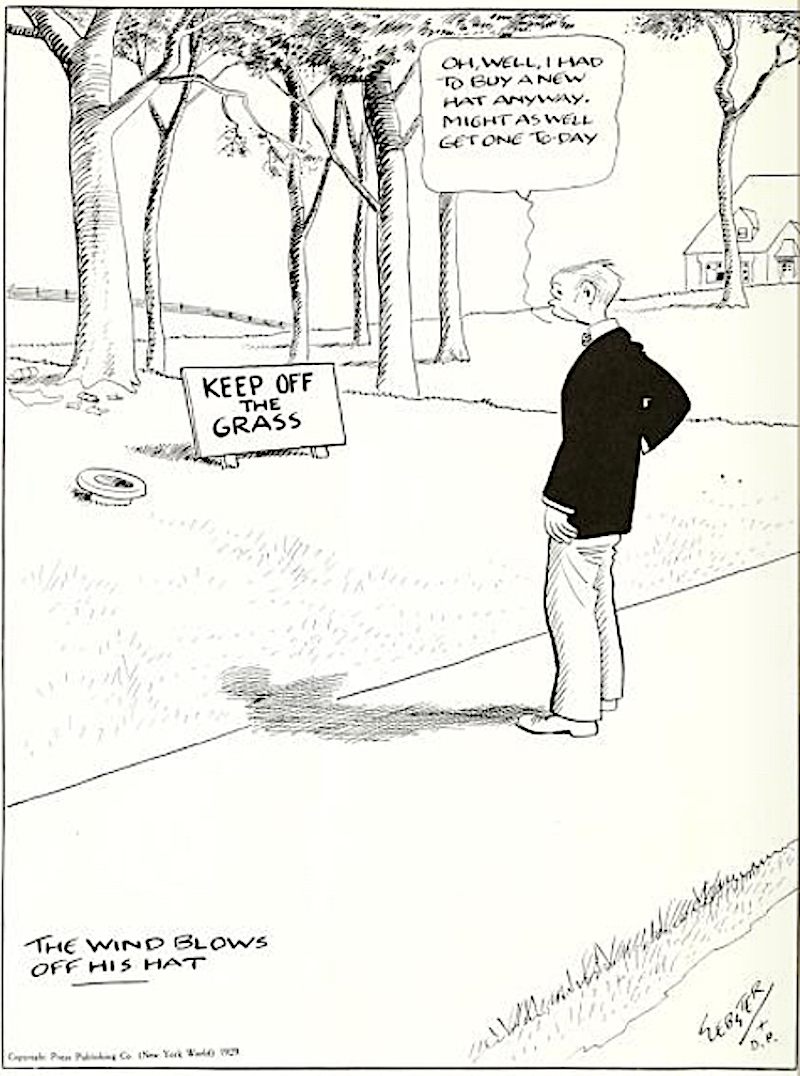

Good heavens. This guy is the living embodiment of Casper Milquetoast, the famous invention of legendary cartoonist H.T. Webster. Casper was the original weenie, so terrified of making mistakes, defying authority or breaking rules that he was in a constant case of paralysis. The idea of a story at a memorial service or funeral is to reveal something characteristic, admirable or charming about the departed and, if possible, to move or entertain the assembled. This guy is the only one alive who can recount whatever the anecdote is, so to the extent it exists at all now, he is the only authority and witness. So what if his memory isn’t exactly accurate? What’s he afraid of?

The advice I’d be tempted to give him is, “You sound too silly to be trusted to speak at anyone’s funeral. Why don’t you leave the task to somebody who understands what the purpose of such speeches are?” Or maybe tell him to watch the classic Japanese film “Rashomon,” about the difficulty of establishing objective truth. “The Ethicist,” who shouldn’t have selected such a dumb question in the first place, blathers on about how “everybody does” what the inquirer is so worried about and cites psychological studies about how we edit our memories. Blecchh.

To begin the year, “The Ethicist” went to the other extreme, publishing a question about a situation that I not only regard as “ethics zugswang” [as in, “Whatever you do will be unethical”] but double secret ethics zugzwang, meaning the horrible situation where you will never know just how unethical it was.

“Should a 13-Year-Old Be Pressured Into Having an Abortion?“ [Gift link!]was the headline. The long letter describes “a newly pregnant 13-year-old.” At this time, she “does not want to terminate her pregnancy, although it also does not seem that she necessarily wants to continue her pregnancy.” Her mother is “walking the fine line of trying to maintain a relationship with her daughter while firmly guiding her toward terminating the pregnancy” because the mother comes from a family with a history of poverty and an inter-generational cycle of teen pregnancy.

Does the 13-year-old have any autonomy in such a situation? Should she have? Can she give meaningful consent to either an abortion or be capable of making the life-altering decision to give birth to the child? The family is not wealthy, and, though the inquirer for some reason speaks in codes about its “demographic,” is apparently black. That tends to make adoption less likely.

Prof. Appiah disqualifies himself as a reliable resource with this single sentence in his response, as he sides with the child’s mother who is pushing the girl to have an abortion. He writes, “I acknowledge that there are thoughtful people who believe that abortion involves a terrible wrong and who will disagree.” Well, gee, that’s big of you, asshole. Spare me your condescension. The decision at issue involves ending a human life. If an ethicist wants to make a utilitarian argument that the wrong inherent in ending that life is outbalanced by the benefits to the pregnant girl and society of removing the troublesome being from the equation, fine—make it. To simply ignore that whole issue, however, is both cowardly and irresponsible.

And unethical.

Just to set the stage for the “there’s only one life involved here, and it’s the girl’s” chorus, I’ll stipulate that the girl is not only pregnant, but pregnant because she was raped by her father. Now what? I suppose “The Ethicist” would say that this new data makes the decision easier. No, it doesn’t—not if you accept, as you must, that there are two lives involved, not just one. That life does not have a lesser value because of the manner in which it came into being.

Should a child ever be forced into agreeing to end the life of her own child? Is a 13-year-old capable of giving informed consent? Should the context of this ethical dilemma change the ethical balance? Why should this unborn child be sacrificed because its mother’s family has a habit of getting knocked-up in their teens? In many such situations, the grandmother raises the baby. The hints being dropped by the inquirer suggest that the pregnant girl has no father in her life, and the mother isn’t in a secure enough position to take on that responsibility, or doesn’t want to.

I’ll admit it: I don’t know what I would say is the “best” or “most ethical” resolution of such a disaster. I will share this: I had a good freind, my secretary and assistant for many years, who became pregnant as a minor, and her family was not well-off. She had to drop out of school, but she had the child, a baby girl. This smart, resilient and courageous woman supported herself and her family (she had a second child in a subsequent, short-lived marriage) as a single mom, struggled and worked as hard as anyone I have ever known—and raised two, happy, successful kids, now grown and married with children themselves. She told me that although her unwanted pregnancy spun her life into an orbit she never would have chosen without it, she never regretted accepting the responsibility of giving birth to a child as a teenager.

This example doesn’t prove what the right course is for an adult guiding a 13-year-old through this ethics Scylla and Charybdis. It does show, however, that whatever the right decision is, reaching it is more complicated than “The Ethicist’s” facile but comfortably woke analysis that doesn’t include consideration of the unborn child’s life at all.

I’m single and childless, but I’ve thought about what I’d do if a daughter of mine got pregnant as a minor, and this is the scenario I’ve come with. Me and the wife sit down with the daughter, and ideally her boyfriend, and his parents (all this is assuming the pregnancy was from consensual sex).

In general, I agree with your options. The only one I’m a bit concerned about is the option where she marries her boyfriend. Yes, it is a valid option but putting two irresponsible young people who haven’t graduated from high school into a marriage that will soon involve an innocent child is often a recipe for disaster. Just my two cents.

” ‘You sound too silly to be trusted to speak at anyone’s funeral.’ “

The meanest, most hated man in the shtetl dies, and a rabbi from the next town over, who knows how much the man was disliked but never knew him personally, is called in as a ringer.

Conducting the ceremony for a sullen congregation, the rabbi is surprised that no one, not even his family, steps forward to eulogize the departed. He thought however hated the man was, he still deserved some kind words as he was being sent off to the next world.

As things wound down. the rabbi spoke out: “Doesn’t anyone have something nice to say about this man?”

Silence.

“We’re here to pay our respects! There isn’t one good thing you can say about him?”

Longer silence; but finally from the back of the room came a voice:

“His brother was worse!”

PWS