July 3 was the final day of the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, reaching its bloody climax in General Robert E. Lee’s desperate gamble on a massed assault on the Union center. In history it has come to be known as Pickett’s Charge, after the leader of the Division that was slaughtered during it.

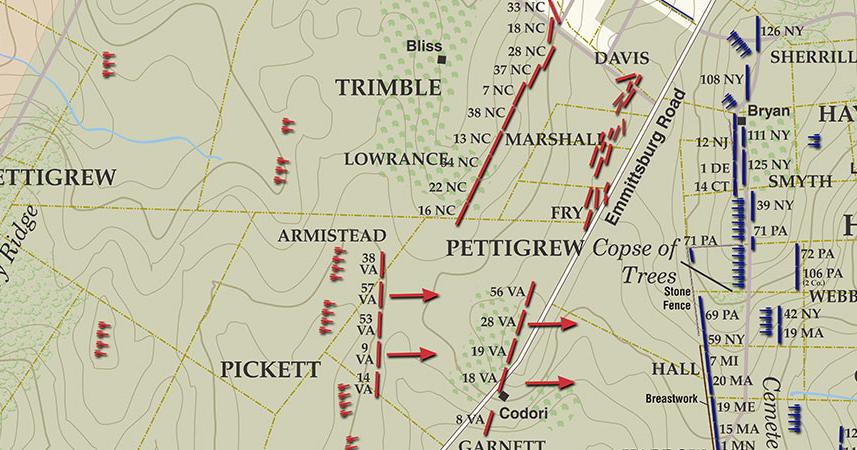

At about 2:00 pm this day in 1863, near the Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg, Lee launched his audacious stratagem to pull victory from the jaws of defeat in the pivotal battle of the American Civil War. The Napoleonic assault on the entrenched Union position on Cemetery Ridge, with a “copse of trees” at its center, was the only such attack in the entire war, a march into artillery and rifle fire across an open field and over fences. When my father, the old soldier, saw the battlefield for the first time in his eighties, he became visibly upset because, he said, he could visualize the killing field. He was astounded that Lee would order such a reckless assault.

The battle lasted less than an hour. Union forces suffered 1,500 casualties,, while at least 1,123 Confederates were killed on the battlefield, 4,019 were wounded, and nearly 4000 Rebel soldiers were captured. Pickett’s Charge would go down in history as one of the worst military blunders of all time.

At Ethics Alarms, it stands for several ethics-related concepts. One is moral luck: although Pickett’s Charge has long been regarded by historians and scholars as a disastrous mistake by Lee and in retrospect seems like a rash decision, it could have succeeded if the vicissitudes of chance had broken the Confederacy’s way. Then the maneuver would be cited today as another example of Lee’s brilliance, in whatever remained of the United States of America, if indeed it did remain. This is the essence of moral luck; unpredictable factors completely beyond the control of an individual or other agency determine whether a decision or action are wise or foolish, ethical or unethical, at least in the minds of the ethically unschooled.

Pickett’s Charge has been discussed on Ethics Alarms as a vivid example, perhaps the best, of how successful leaders and others become so used to discounting the opinions and criticism of others that they lose the ability to accept the possibility that they can be wrong. This delusion is related to #14 on the Rationalizations list, Self-validating Virtue. We see the trap in many professions and contexts, and its victims have been among some of America’s greatest and most successful figures. Those who succeed by being bold and seeing possibilities lesser peers cannot perceive often lose respect and regard for anyone’s authority or opinion but their own.

Pickett’s Charge also stands for the duty to prevent a disaster that you know is going to occur, the whistleblower’s duty, and the theme of Barbara Tuchman’s work, “The March of Folly.” Historian Shelby Foote, in Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary, says that it was easier for Lee’s men to walk across that field and risk a futile death than to defy the man they respected so much. Yet General Longstreet, whose men undertook the doomed charge, claimed he knew that it would fail and that he couldn’t even give the order to begin, eventually just nodding his head. Well, if he knew Lee’s strategy would fail, he had an obligation to do everything he could to stop it. He was in the position of the engineers who knew the Space Shuttle Challenger was going to blow up if launched in freezing weather.

Robert E. Lee’s noble and unequivocal acceptance of accountability for the disaster, telling the returning and defeated warriors that “It is all my fault” is another ethics milestone. In my view, this incident alone justifies the statues and memorials to Lee, a flawed general and human being, but a leader worth studying and remembering. When General Dwight D. Eisenhower, having given the order to proceed with the Normandy invasion despite bad weather conditions, penned a note to be published should the assault fail. In the statement Ike took full responsibility for decision, deliberately emulating Lee. At the same time, Pickett’s Charge teaches that leadership requires pro-active decision-making, and the willingness to fail, to be excoriated, to be blamed, is an essential element of succeeding.

Pickett’s Charge also shows how, as baseball writer and one of my ethics gurus Bill James explained, nature conspires to make us unethical.

More or less simultaneously with Picket’s Charge, my favorite neglected episode of the Civil War took place. Young hot-head `George Armstrong Custer shocked Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart with his unexpected and furious resistance to Stuart’s attempt at disrupting the Union flank while Gen. Meade’s army defended itself against Lee’s bold attack. The incident is especially fascinating because of the its multiple ironies. Custer succeeded when his nation needed him most because of the same qualities that led him to disaster at the Little Big Horn years later. Moreover, this man who for decades was wrongly celebrated in popular culture as an American hero for a shameful botched command that was the culmination of a series of genocidal atrocities actually was an American hero in an earlier, pivotal moment in our history, and almost nobody knows about it.

Thus it is that among the brave soldiers of the Blue and Gray who should be remembered for their role in the greatest battle ever fought on this continent is a figure whose reputation has sunk to the depths, a figure of derision and ridicule, a symbol of America’s mistreatment of its native population. Had George Armstrong Custer perished on July 3, 1863, he might well have become an iconic figure in Civil War lore. The ethics verdict on a lifetime, however, is never settled until the final heartbeat. Custer’s life also commands us to realize this disturbing truth: whether we engage in admirable conduct or wrongful deeds is often less a consequence of our character than of the context in which that character is tested.

Because I have vowed to make sure, in my own modest and limited way, that as many people as possible know about this forgotten event, I’m going to post, once again, the essay from 2011 titled “Custer, Gettysburg, and the Seven Enabling Virtues,” lightly revised.

***

July 3, 1863 marked the zenith of the career of George Armstrong Custer, the head-strong, dashing cavalry officer who would later achieve both martyrdom and infamy as the unwitting architect of the massacre known as Custer’s Last Stand.

Custer’s heroics on the decisive final day of the Battle of Gettysburg teach their own lessons, historical and ethical. Since the East Calvary Field battle has been thoroughly overshadowed by the tragedy of Pickett’s Charge, it is little known and seldom mentioned. Yet the truth is that the battle, the war, and the United States as we know it may well have been saved that day by none other than undisciplined, reckless George Armstrong Custer.

Lee’s plan, along with Pickett’s Charge, was to have J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry attack the Union line from the rear as the Blues were facing the advance by Pickett’s division. Had the Union forces believed themselves surrounded, Lee’s tactic of attacking with a massed, relentless, attacking line might have had its desired psychological effect and broken the North’s resolve.

Stuart’s mounted force met Union artillery as he approached, so the Confederate general ordered a cavalry charge. Custer, by some luck and the alertness of cavalry commander Gen.David M. Gregg, was on the scene to try to foil the advance. The smaller Union force met Stuart’s mounted warriors head-on in furious hand-to-hand combat, with Custer personally leading the fighting. Custer’s own horse was shot out from under him, so he commandeered a bugler’s horse and continued the assault.

General Stuart’s Virginians retreated, but not for long. Stuart called up reinforcements, and pushed the Union cavalry back. When it appeared that the Confederate cavalry would break through, Custer, whose forces were badly outnumbered, called for a second attack by his Michigan Calvary Brigade. Shouting “Come on, you Wolverines!”, Custer commanded another attack, this one at a full charge to meet the charging enemy…a tactic that was as rare as it was considered foolhardy. One stunned witness recalled,

“As the two columns approached each other the pace of each increased, when suddenly a crash, like the falling of timber, betokened the crisis. So sudden and violent was the collision that many of the horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them.”

Custer had a second horse shot out from under him, but his courageous and reckless exploits broke Stuart’s advance, and ruined that component of Lee’s strategy.

Would Lee’s grand gamble have paid off with victory if Stuart had reached the rear of the Union forces on Cemetery Ridge? No one will ever know, but here is the opinion of one participant, Lt. Brooke-Rawle, who later became the principal historian of the East Cavalry Field fight. He wrote:

“We cavalrymen have always that we saved the day at the most critical moment of the battle of Gettysburg-the greatest battle and the turning point of the War of the Rebellion. Had Stuart succeeded in his well-laid plan, and, with his large force of cavalry, struck the Army of the Potomac in the rear of its line of battle, simultaneously with Pickett’s magnificent and furious assault on its front, when our infantry had all if could do to hold on to the line of Cemetery Ridge, and but little more was needed to make the assault a success, the merest tyro in the art of war can readily tell us; fortunately for the Army of the Potomac, fortunately for our country, and the cause of human liberty, he failed. Thank God that he did fail, and that, with His divine assistance, the good fight fought here brought victory to our arms!”

We do know that Custer’s trademark flamboyance and impetuousness, the same qualities that later would doom him and his men at the Little Big Horn, helped ensure the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg.

In many ways, George Armstrong Custer was neither a trustworthy commander nor a good man. After the war, he led soldiers who committed numerous atrocities against Native Americans, and was willing to risk the lives of others to serve his own military reputation and ambition. Custer, however, possessed many of the most useful tools of ethical conduct, which I call “The Seven Enabling Virtues.” While not ethical in themselves, these character traits—courage, valor, fortitude, sacrifice, honor, forgiveness and humility—greatly assist us in behaving ethically, especially under challenging circumstances.

The lingering trap is that these tools can be used in the service of right or wrong, and can lead an individual to do as much harm as good. They are also prone to leading us to behave irresponsibly or unfairly. Courage can become recklessness; valor can curdle into showboating; fortitude can turn to stubbornness; sacrifice may become callousness; honor may beget vanity; forgiveness to excess encourages apathy and passivity, and humility plants the seeds of submissiveness. Custer’s courage, valor, fortitude and sacrifice served his nation and humanity well on July 3, 1863. On June 25, 1876, they helped get him and the 210 soldiers under his command slaughtered.

Without constant vigilance and a strong and evolving sense of ethics, even the enabling virtues can trigger misconduct and disaster. On July 3, I always reflect on Custer’s grand heroism when his country needed it most, and how strange it is that he is best remembered for his worst blunder, when his greatest achievement was so much more important. I also think about how his life is a cautionary tale, reminding us of how easily our strengths can become our weaknesses, if we fail to understand how best to use them, or recognize when they are leading us astray.

i wonder if Stonewall Jackson could have steered Lee away from this disastrous assault, reminding him how doing the same thing had gone so badly for the other side at Fredericksburg.

I watched the extended version of “Gettysburg” in honor of Pickett’s Charge, and liked the movie even better than I had in the past. And the comparison to Fredericksburg was vivid. I had forgotten that the Union Army chanted “Fredericksburg!” at what was left of Pickett’s division.

I have been perhaps too active lately on the Quora Civil War forums, and Gettysburg is a favorite topic there including Pickett’s charge.

Here is one aspect that has come up a number of times. We concentrate on the idea that Pickett’s charge was a doomed endeavor, that the idea of sending 15,000 men across an open field to attack prepared fortifications was bound to fail — and all that is true.

But wait, there’s more!

Let’s suppose that Lee’s concept was correct. That a charge by his veterans could actually have broken the Union line at the point of attack. Things like that did happen on occasion during the war (I’m especially thinking Missionary Ridge the previous year). And Pickett’s men — a few of them — did actually reach the Union line.

So what happens then? Does the Army of the Potomac all turn around and run for the hills?

Well, so you’re in Pickett’s division and you walk a mile over that field, you climb over that stone fence and break the Pennsylvanians in front of you. And then you turn the task over to the exploitation division following behind that will decisively rout the Federals……….

But. When you turn around there is no exploitation force. There is no one there to take advantage of your hard won victory. You’re there all by yourself — and presently the Yankees close ranks and scoop you and whatever corporals guard is left.

This, several of us have concluded is the real failing of Robert E Lee. He had no real strategic vision, no war winning strategy. Crudely put, he saw a Union army in front of him and basically said “I will attack and beat that army and then somehow the Union will give up and grant our independence.

Ulysses S. Grant, on the other hand, spent his first months as supreme U.S. commander crafting a continent wide coordinated strategy of attacks that would destroy the Confederacy as a nation and polity. Not everything worked as planned, there were setbacks. But when Grant was checked, he made adjustments and moved on to the next phase of his campaign.

Grant, in my opinion, was one of the greatest military geniuses the United States — or any country — has ever produced.