Before you make a public statement that will guarantee that you will become a poster-mayor for the usual “War on Christmas” battles, it might be wise to check legal history regardless of which position you take.

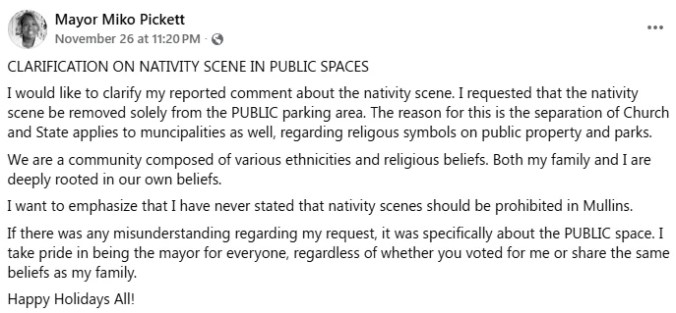

Mayor Miko Pickett, the “historic” first black mayor of Mullins, South Carolina, ordered this season’s Nativity scene removed from a public parking lot due to “separation of church and state.” The town happily ignored her. Not surprisingly, she had based her decision on “diversity” and “inclusion” principles and the “separation of Church and State.”

Naturally, she opted for the politically correct “Happy Holidays.” But the mayor may have had a point.

A narrow 5-4 majority in the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lynch v. Donnelly (1984) acknowledged the nation’s status as one friendly to Christianity in general and the secular holiday of Christmas specifically. In the flickering death throes of the extreme liberal Warren Court, the conservatives on the Burger Court struck a blow for the secular holiday of Christmas, and ruled that a city acknowledging its origins did not constitute the state endorsing one religion over another.

The Court upheld a city’s Nativity scene, or “creche,” against an Establishment Clause challenge. Pawtucket, Rhode Island, included a creche in its annual Christmas display for over 40 years, along with items like Santa’s house, a Christmas tree, a banner reading “Season’s Greetings,” and a reindeer pulling a sleigh. By a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court held that the display, despite including the creche, did not violate the Establishment Clause.

The Court grounded its decision in what it said was the legitimate secular purpose of the creche. The display, taken as a whole, was “sponsored by the city to celebrate the Holiday and to depict the origins of that Holiday,” and the creche was “passive,” “like a painting” in a government-sponsored museum.

What saved the Nativity scene was that the display also included a reindeer and a sleigh, making it the symbol of “a friendly community spirit of goodwill in keeping with the season,” and any benefit “to one faith or religion or to all religions, [was] indirect, remote, and incidental.” In her concurring opinion to the majority’s ruling authored by Chief Justice Burger, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor added that the “celebration of public holidays, which have cultural significance even if they also have religious aspects, is a legitimate secular purpose.”

Five years later, in County of Allegheny v. ACLU (1989), the Court vetoed a creche on the county courthouse steps. It was surrounded by poinsettia plants, two Christmas trees, and an angel bearing a banner that read, “Gloria in Excelsis Deo,” or “Glory to God in the Highest.” In a wildly split decision featuring six opinions including three opinions concurring in part and dissenting in part for opposite reasons, five justices found this display to endorse Christianity violating the First Amendment. The same three liberal justices who had voted to strike down the Pawtucket display also agreed that this one had to go. Justices Blackmun and O’Connor for the majority distinguished the creche in Pawtucket because the Allegheny Nativity had “nothing in the context of the display [to detract] from the creche’s religious message…Santa’s house and his reindeer were objects of attention separate from the creche, and had their specific visual story to tell.” Poinsettia plants and Christmas trees don’t count.

And thus was born the so-called “Reindeer Rule”: a city can have a manger scene, but only if it either includes displays featuring other religious symbols (like a Menorah) or includes non-religious images, like Santa Claus or Mariah Carey.

Justice Kennedy, well into his tenure as the swing vote on the Court but outvoted this time, felt that the Reindeer Rule reflected a mistaken view that “reflects an unjustified hostility toward religion, a hostility inconsistent with our history.” He viewed mangers and other direct references to the Christmas story as “purely passive symbols of religious holidays.” The “government, if it chooses, may participate in sharing with its citizens the joy of the holiday season.” Justice Kennedy wrote. “If government is to participate in its citizens’ celebration of a holiday that contains both a secular and a religious component, enforced recognition of only the secular aspect would signify [a] callous indifference toward religious faith.”

Does the town of Mullins have any reindeer in the vicinity of its display? It doesn’t look like it…

..but wait! Who’s that hiding behind the tree? Could it be…Santa? I think it is! Yes, as I read the two opinions, the right jolly old elf is sufficient to save the manger even without Rudolph.

But whether it is or it isn’t Santa (might those faux candles be secular enough without him? I have neighbors who have lit-up candles like that in front of their house, and I don’t see them as religious), it seems the Mayor knows when to back off.

There are some people who believe in ‘The Force’, a religion from the Star Wars franchise. So if the government recognises ‘The Force’ aka ‘The Jedi Religion’ as a religion, will people then be stopped from Star Wars displays?

Remember, people can do whatever they want. Governments can acknowledge a religion, but not openly favor one over the others. So if a town had a manger and Menorah, if “The Force” cult wanted to display Yoda next to them, I’m assuming the town would have to comply.

I just heard that Gene Autry song on an Apple Music Christmas playlist. Funny, when I heard the song I recalled that my grandfather was in the hospital when Mr. Autry had his eye surgery at Mass Eye and Ear in 1971, and he said he was one of the nicest people he ever met. Couldn’t say enough about him. That stuck with me all my life.

It would seem to me that if you want to acknowledge or allow a respectful display that depicts a religious event by government without suggesting advocacy all that is needed is to allow any bona fide religion the opportunity to create displays for their main event.

Secular humanism is as much a religion as Christianity or Buddhism. To suggest it is acceptable to only allow a crèche if accompanied by a red nose reindeer or a Santa (Paganism) should also mean that Christmas trees or Elves cannot be displayed without a crèche, a Menorrah, or some other thing.

Going a step farther means that government cannot pay a premium for an employee working on Christmas Day.

The concept of separation of church and state never meant freedom from religion.

The mayor in this case is not a fool. She presumably has since read the decisions or had someone read them for her and gotten better advice. Most towns by now have gotten the memo and invested in some secular Christmas figures to go alongside the manger, leaving it for the churches to put up the manger scenes alone. Those that had Jewish populations were probably already in the clear because they had menorahs in place. A lot of them haven’t bothered, though, because no one has bothered them.

I think I’m not off base when I say many, probably even most, agnostics or atheists don’t give two candy canes if there is a nativity scene in the middle of the square, because they can’t be bothered, it doesn’t harm them, and they don’t want to look like Scrooge. Truth be told, they’d look even worse than Charles Dickens’ miser, because although before the ghosts Scrooge disliked Christmas and wanted nothing to do with it himself, he didn’t interfere with other people celebrating, even if he may have grumbled about it.

It’s the militant atheists who bring these vexing suits that get all the other nonbelievers a bad name. To the majority of this country Christmas is a very big deal, or at least some kind of deal, even if most of us don’t keep it the rest of the year and a lot of us need to seriously work on our character. The world is dark enough without haters, for that’s what a militant atheist is, but he gets a pass because he hates all religion, not just one, without them trying to extinguish one of the lights we do have. You’d think by now they would have gotten the message after the Bladensburg cross case a few years back, but like hope hate springs eternal.

I recall a story some years ago about a group that solved their problem by putting Santa Claus in a Nativity Scene….kneeling in front of the manger in reverence.

Smart move and hilarious.