You expected to see one of the train wreck graphics didn’t you? Well, this is a train wreck graphic…

You expected to see one of the train wreck graphics didn’t you? Well, this is a train wreck graphic…

Usually humor is not something Ethics Alarms associates with ethics train wrecks, but the ridiculous bi-partisan Jeffrey Epstein Ethics Train Wreck is already producing a large number of metaphorical appearances by Nelson Muntz…you know, the mocking “Simpsons” character?…

…with more certain to come. The lesson here, it appears , is “Don’t play Cognitive Dissonance Scale games if you don’t understand the rules!”

…with more certain to come. The lesson here, it appears , is “Don’t play Cognitive Dissonance Scale games if you don’t understand the rules!”

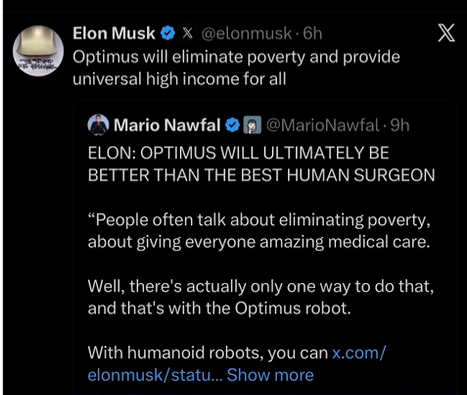

First, the Republicans made releasing the “secret files” about long-dead and even longer-disgraced sex-trafficker and pervert Jeffrey Epstein a 2024 campaign issue for idiots. (The national welfare will be neither enhanced nor harmed by anything regarding Epstein at this point, but the matter was a campaign squirrel. The news media, however, as it has an Epstein addiction that began once Bill Clinton seemed out of harm’s way, couldn’t resist. )

Then Trump was elected and appointed a none-too-bright Attorney General (Pam Bondi) and an incendiary FBI chief (Kash Patel) who soon said “Surprise! There are no Epstein files or nothing is in them or something!” This (predictably) inflamed the idiots, particularly Democrat idiots, who decided, “AHA! There must be something that will allow us to smear Trump and derail his second term like we did the first one with the fake Russia collusion investigation!” The idiot voting bloc is, one must admit, unusually large, so the Democratic Party has been using Epstein with some success—aided by their unethical news media, aka. “the news media,” which elevated Epstein files rumor-mongering and “Trump must have something terrible to hide, because he’s terrible” stories ahead of substantive news that the public genuinely needed to know.

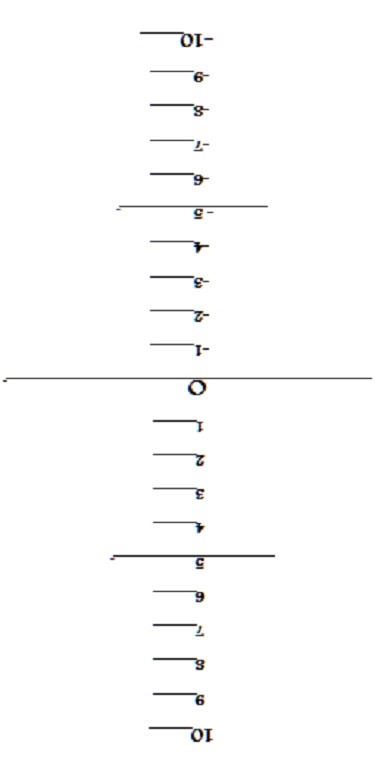

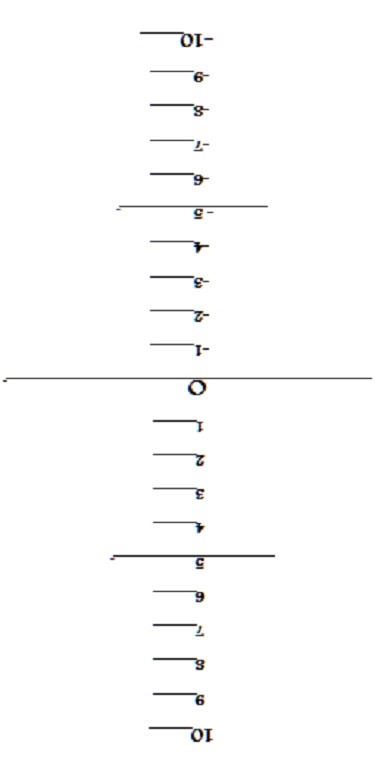

Now it became the old Cognitive Dissonance Game…you must know the drill by now. Here’s Dr. Festinger’s invaluable scale showing how we form and maintain our attitudes toward, well, everything:

Continue reading →