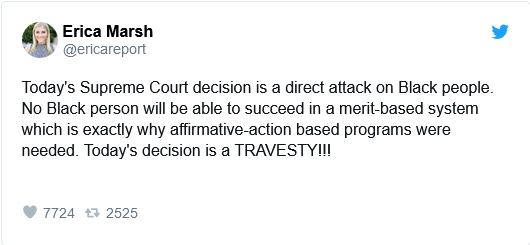

Good.

Much about this was predicted and predictable: the split, 6-3, in which the diversity trio (A wise Latina, the historic black woman, and a lesbian) took their required stand, and the decision’s spokesjustice, Roberts, who had signaled this result by famously saying, last time around this controversy, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” However, many thought the opinion would ultimately provide wiggle room for colleges, and it does not. From the opinion, here, by Chief Justice Roberts, who reflected on Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s observation in a previous affirmative action case that “25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today” (which signaled that the Court was allowing an exception to Constitutional requirements continue for a limited period):

Twenty years later, no end is in sight. “Harvard’s view about when [race-based admissions will end] doesn’t have a date on it.” Tr. of Oral Arg. in No. 20–1199, p. 85; Brief for Respondent in No. 20–1199, p. 52. Neither does UNC’s. 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 612. Yet both insist that the use of race in their admissions programs must continue.

But we have permitted race-based admissions only within the confines of narrow restrictions. University programs must comply with strict scrutiny, they may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and—at some point—they must end. Respondents’ admissions systems—however well intentioned and implemented in good faith—fail each of these criteria. They must therefore be invalidated under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment….

It is true that our cases have recognized a “tradition of giving a degree of deference to a university’s academic decisions.” Grutter, 539 U. S., at 328. But we have been unmistakably clear that any deference must exist “within constitutionally prescribed limits,” ibid., and that “deference does not imply abandonment or abdication of judicial review,” Miller–El v. Cockrell, 537 U. S. 322, 340 (2003). Universities may define their missions as they see fit. The Constitution defines ours. Courts may not license separating students on the basis of race without an exceedingly persuasive justification that is measurable and concrete enough to permit judicial review.

I particularly want to applaud Roberts’ clear statement that the use of “diversity” by colleges to justify discrimination is undefined, pie-in-the-sky hooey, if not outright flim-flammery:

Unlike discerning whether a prisoner will be injured or whether an employee should receive backpay, the question whether a particular mix of minority students produces “engaged and productive citizens,” sufficiently “enhance[s] appreciation, respect, and empathy,” or effectively “train[s] future leaders” is standardless. 567 F. Supp. 3d, at 656; 980 F. 3d, at 173–174. The interests that respondents seek, though plainly worthy, are inescapably imponderable.

Later, the Chief chides Harvard et al. for the obvious phoniness and arbitrary nature of their categories:

Continue reading →