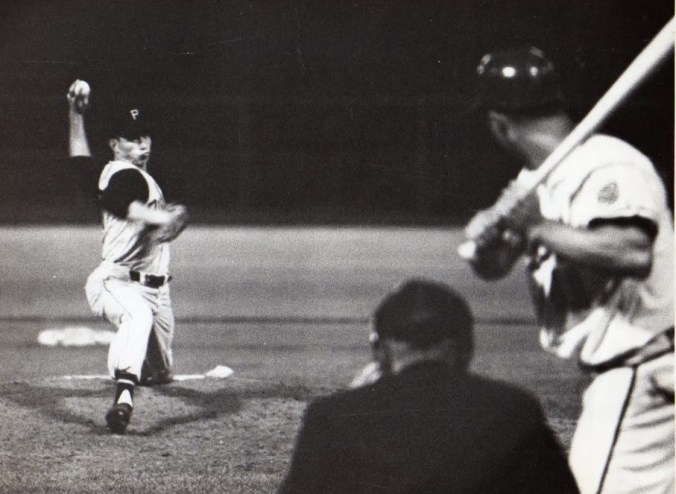

That’s Harvey Haddix about to throw a pitch above. The photo is from one of the most famous baseball games ever played: on May 26, 1959, Haddix, then a starting pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates pitched a perfect game—that’s no runs, hits, walks or errors, with nobody on the other team reaching base) for 12 innings against the Milwaukee Braves. It was the greatest pitching performance of all time, but because the Pirates didn’t score a run either, Haddix had to keep pitching into the 13th inning, where he lost the perfect game, the shutout and the game itself. As a result, he wasn’t even given credit for a no-hitter, which is normally when a pitcher throws nine-innings of hitless ball. That really bothered me as a kid; it made no sense.

In baseball, a no-hitter, with a perfect game being the ultimate no-hitter, has always been considered one of pinnacles of single game performance by a baseball player. A pitcher who throws one gets his name in the Hall of Fame; it’s a distinction that accents an entire career. Only the greatest pitchers throw more than one in a career; some of the very greatest, like Lefty Grove, Grover Cleveland Alexander, and Roger Clemens, never get one. (Cy Young, Nolan Ryan and Sandy Koufax, however, tossed three or more each. Johnny Vander Meer tossed two no-hitter in consecutive starts!) So being credited with a no-hitter is important; it matters.

Imagine then what it would feel like to be credited with pitching a major league no-hitter (or have your father or grandfather credited with one) and have it taken away. That’s what happened in 1991. Up until then, there had been no specific definition of no-hitter except the obvious, common sense one used by sportswriters, players, fans and baseball historians: a no-hitter was a baseball game that ended with one team having failed to get a hit. One of my favorite Commissioners of Baseball, however, Fay Vincent, the last one who wasn’t a toady for the baseball team owners (Vincent was fired for being independent, which up until then was the definition of his job), decided that the definition of no-hitter was too loose, among some other statistical anomalies. He put together a commission, and, with his influence, they redefined a no -hitter as a game that ended with one team getting no hits in at least nine innings.