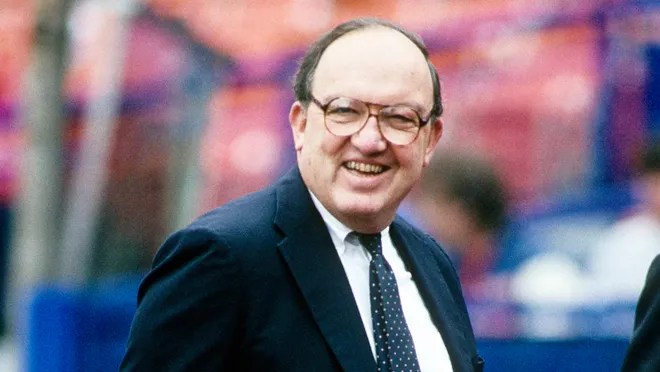

Fay Vincent, the last real Commissioner of Baseball, has died and attention should be paid.

The post of Commissioner of Baseball was created in the wake of the 1919 Black Sox scandal, with baseball’s future in doubt after the revelation that key members of the Chicago White Sox had accepted money from gamblers to throw the World Series to the vastly inferior Cincinnati Reds of the National League. The desperate owners turned to an austere judge, the wonderfully named Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who accepted the job provided that he had absolute power to act in “the best interests of the game.”

Landis ruled with an iron hand and baseball’s perpetually corrupt, greedy and none-too-bright owners backed off while he was in power, from 1920 until his death in 1944. Landis, in the harsh light of hindsight, is now vilified for not figuring out that keeping blacks out of the Major Leagues wasn’t in the best interests of baseball (or blacks, or sports, or democracy, or society, or the nation), but he proved a tough act to follow nonetheless.

Most of his successors were mere figureheads or knuckleheads, notable more for their non-decisions and bad ones than their actions in the “best interests of baseball.” Ford Frick, one of the longest serving Commissioners, is best known for his foolish insistence that Roger Maris didn’t really break Babe Ruth’s season homer record, a controversy decisively ended in the American League three years ago by Aaron Judge. Baseball collected weenies and fools in the role because the owners wanted it that way.

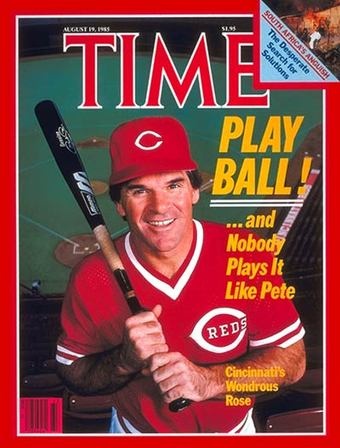

There were a couple of exceptions. Peter Ueberroth made the game infinitely more profitable and considerably more popular by modernizing its brandingm merchandising, promotion and marketing. Bart Giamatti , following in the fading footsteps of Judge Landis, courageously refused to issue The King’s Pass to Pete Rose, one of the most popular former players in the game, and banned him for gambling. But when Giamatti died suddenly from a heart attack after less than a year as Commissioner, he was succeeded by Fay Vincent, in a sequence a bit like when the Vice-President takes over when a POTUS dies. He had been deputy commissioner under his good friend Giamatti, and the owners of the major league teams confirmed him without qualms as the next Commissioner . They thought he was one of them: a corporate veteran and lawyer who had served in top executive roles for Columbia Pictures and Coca-Cola before Giamatti recruited Vincent as his right-hand man.

Vincent, however, was not what the owners wanted or expected. He was intelligent, courageous, far-sighted, and worst of all, as a passionate baseball fan, he took his job description seriously and literally. He didn’t work for the owners, though they could fire him. His stakeholders were fans and the game itself. Vincent’s vision for the job was reminiscent of the difficult ethical conflict accountants face: businesses hire them and pay their salaries, but their duty is to the public.