New commenter Christine has a valuable personal experience to relate, as an individual who donated a kidney to a stranger herself. The main thrust of her post covers a topic that I have written on before but did not mention in this case, though I should have. Someone who performs a kind and generous act counting on rewards, copious thanks and gratitude, is doing it for the wrong reasons. The act itself is all that matters. Certainly, gratitude is the right way to respond to generosity, but an act done in anticipation of personal benefits isn’t really altruistic. It is opportunistic. This is a cliché to be sure, but true nonetheless: the generous act must be its own reward.

New commenter Christine has a valuable personal experience to relate, as an individual who donated a kidney to a stranger herself. The main thrust of her post covers a topic that I have written on before but did not mention in this case, though I should have. Someone who performs a kind and generous act counting on rewards, copious thanks and gratitude, is doing it for the wrong reasons. The act itself is all that matters. Certainly, gratitude is the right way to respond to generosity, but an act done in anticipation of personal benefits isn’t really altruistic. It is opportunistic. This is a cliché to be sure, but true nonetheless: the generous act must be its own reward.

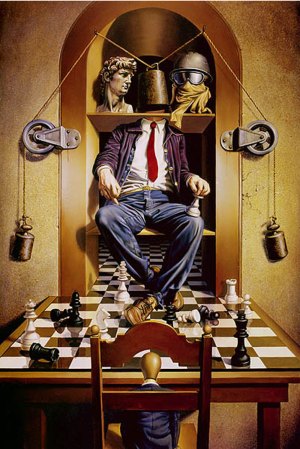

Here is Christine’s Comment of the Day on the post, Ethics Chess Lesson: The Tale of the Kidney and the Ungrateful Boss.

I want to also commend Christine for following the comment policies, which many of the new visitors here who commented on this post did not do. I prefer full named on posts, but I only require that I am informed of every commenter’s real name and have a valid e-mail address within a reasonable time of their first submitted comment. One way or the other virtually all of the regular commenters here have managed to do this, and it makes a difference, even in my responses. I regard such commenters as collaborators , not just marauders, and most of the time, I treat them accordingly: tgt, Steven, Lianne, Margy, Glenn, Tim, both Michaels, Karl, Neil, Karla, Rick, blameblakeart, Barry, gregory, Eric, Curmudgeon, Eeyore, Julian, King Kool, Joshua, Jay, Tom, Bill, Danielle, Elizabeth, Patrice, Ed, Bob, The Ethics Sage and Jeff…I know there are others. Thanks to all of you for letting me know who you are.

Now, Christine: Continue reading