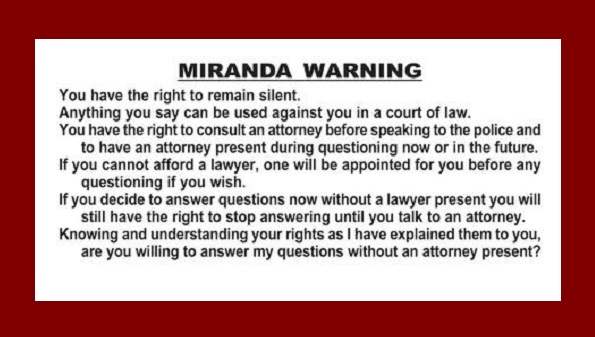

Devin Malik Cunningham, 21, is accused of the robbery and murder of a 71-year-old man. His lawyers argued that his confession should be excluded from the trial because he didn’t understand the Miranda warning given to him when he was arrested. Specifically, Cunningham claims that testified that he was confused when asked whether he wanted “an attorney,” and that is why he agreed to speak with police. He said that he thought an attorney is a judge.

No wonder he didn’t want to speak to a judge. Judge William Amesbury of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania ruled that his claim was absurd, noting that there was no evidence of a cognitive or learning disability that would support Cunningham’s alleged misunderstanding.. There was also evidence that an arresting officer explained during questioning that an attorney is a lawyer.

I wonder what is the presumed understanding of basic English vocabulary words for an English speaker. Cunningham’s Hail Mary defense, if accepted, might have opened up a brand new avenue for accused criminals, sexual harassers, and those derided as uncivil. I think he may have made a bad choice regarding what he thought “attorney” meant. Why not plead complete confusion: he thought an attorney was a platypus! Or a salve for athlete’s foot!