In the strange ethics category of “Conduct That Isn’t Exactly Wrong But That Will Have Nothing But Bad Consequences To Society If There Is A Lot Of It” (CTIEWBTWHNBBCTSITIALOI for short) is actors rejecting roles because they have philosophical or political disagreements with the script.

We’ve had two high profile examples of this occur lately. All we can do is hope that it’s a coincidence. The first was when about a dozen Native American actors, including an adviser on Native American culture, left the set of Adam Sandler’s first original movie with Netflix, “The Ridiculous Six,”a western send-up of “The Magnificent Seven,” claiming some of the film’s content was offensive.

Really? An Adam Sandler movie offensive?

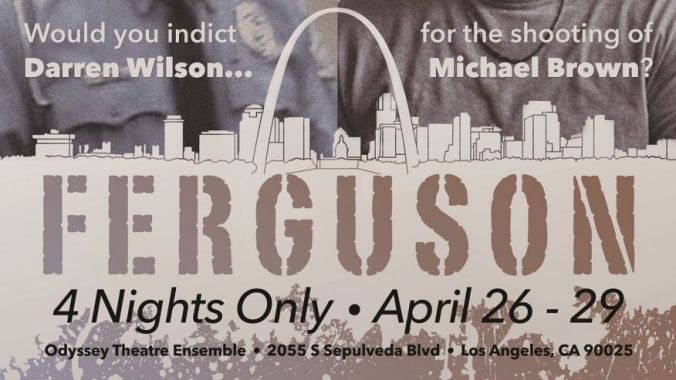

The second and more troubling was in LA, where five actors quit the cast of the new play “Ferguson,” which consists entirely of dramatizations of the Michael Brown murder grand jury testimony, because the actors apparently felt that it did not appropriately support the “Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!” narrative.

That’s really stupid, but I’m not getting into that again.

We don’t see many examples of professional actors doing this for several reasons. One is that they can’t afford to. Acting, except for the top fraction of a per cent, is anything but lucrative; it’s a subsistence level job, redeemable because it is, or can be, art, and tolerable as long as the actor doesn’t have a family to support, or has a trust fund.

The main reason this is unusual, however, is that an actor isn’t responsible for the content of the play, movie or TV show he or she acts in, but only the skill with he or she helps present that content to an audience. Actors—and technical artists like costume and light designers—are the conduits through which a writer’s work of performance art gets to live. They don’t have to like a show, agree with it or understand it, which is a good thing, since many excellent actors don’t have the education, experience or intellect to understand complex and profound works. As one realistic actor friend once told me, “If we were that smart, we’d be smart enough to be in another profession.” Continue reading