What a joy to wake up this morning not only to a spectacular Comment of the Day, but also to a note from an MIA commenter who was last seen in these parts almost nine years ago! I welcome Lisa Smith back to Ethics Alarms with a well-deserved Comment of the Day honor, for her note on the post, “On Lincoln’s Favorite Poem, and the Poems’ We Memorize…”

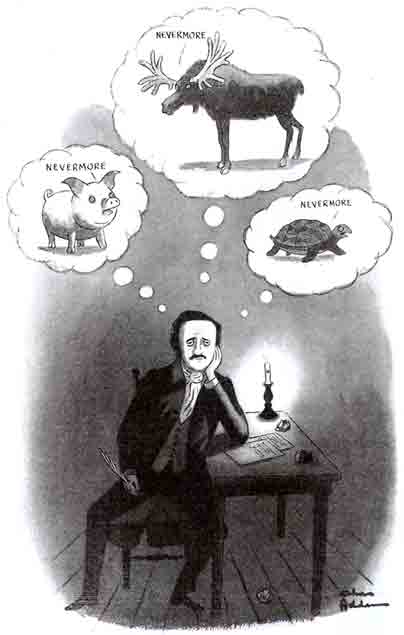

(I couldn’t resist leading this off with one of two brilliant Charles Addams cartoon about “The Raven.” The other has Poe pondering as a raven, perching over his door, says, “Occasionally.”)

***

I don’t know – Poe’s Raven has one of my favorite lines; it isn’t at all profound, but it is profoundly delightful to speak and to allow to roll over the brain like a cool river. I memorized the entire poem when I was a teen in the late 70’s and can still recite it. (But for the life of me, I can’t remember the “new” neighbor’s names, even though they have been here five or six years. Their dog is Annie. My priorities are laid bare, I suppose.)

“And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain thrills me, fills me with fantastic terrors never felt before.”

There may be errors in there. I write it from memory alone. [JM: Pretty close! “And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain, thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before”]

Poetry makes equals of us all. From Bukowski to Shakespeare. They speak to each person in their own way.