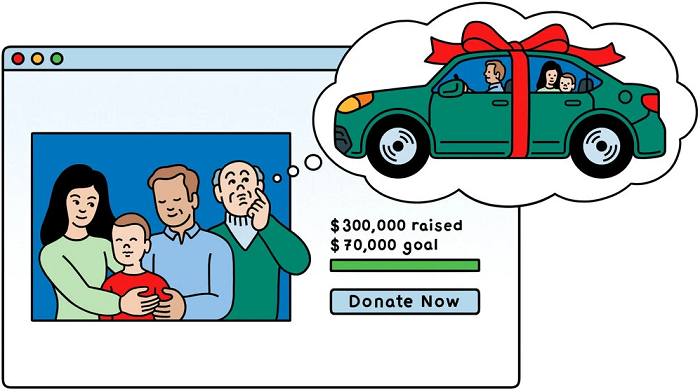

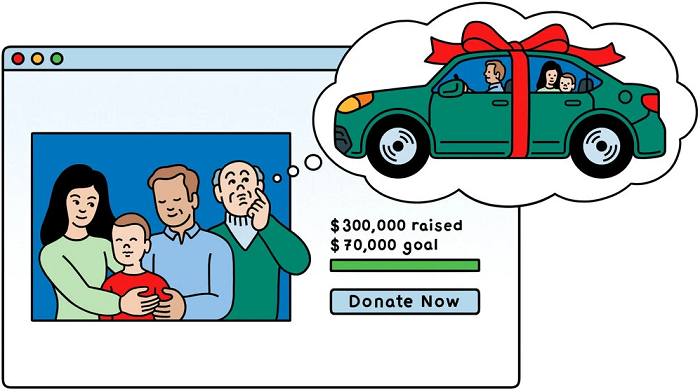

When I read the headlined question in an April installment of “The Ethicist” advice column in the New York Times Magazine, I would have done a spit-take if I had just taken a sip of something. It was “Is It OK to Use Money Raised for a Child’s Cancer Care on a Car?” What? No it’s not “OK,” you idiot! The questioner has to write to a professor of philosophy like Kwame Anthony Appiah, who is the current version of the Times’ ethics expert, to puzzle out that query? Why not ask a neighbor, a minister, a friend who isn’t in jail, a reasonably socialized junior in high school?

Then I started wondering what percentage of American think that question is a really tough one, and I got depressed.

Here was the whole question:

My grandchild is being treated for leukemia. A friend of the child’s parents set up a GoFundMe page for them. They’re both well loved and have siblings who know a ton of people. So the goal was surpassed in three hours, and donations totaled more than double that amount. They plan to donate anything over and above direct hospital-related expenses to leukemia research organizations.This couple have some needs that aren’t strictly related to the child’s care, like a new car. Am I rationalizing by saying they need to drive the child to the hospital and should use some of this money for a dependable car? Is there a strict line you would not cross? And is it germane that they’re not extravagant and extremely honest?

I don’t need to discuss Appiah’s answer; he got it right. If he hadn’t, he would need to have his column, his teaching position at NYU and his degree in philosophy taken away. My concern is how hopelessly inept our culture must be at installing the most basic ethical principles if someone grows to adulthood unable to figure out in a snap that if one receives charity to pay for a child’s medical expenses, it is unethical, indeed criminal, to use the money to buy a car.

This isn’t hard, or shouldn’t be. Why is it? If the GoFundMe raised more money than is needed for the purpose donors contributed, the ethical response is to send the now un-needed fund back, with a note of thanks. (Appiah, after far more explanation and analysis than should be necessary—but he does have a column to fill—-eventually points this out.) No, you do not give the extra contributions to “leukemia research organizations,” because the donors could have contributed to those on their own, and didn’t give the money after a general appeal for all leukemia sufferers. They gave money for this particular child’s treatment. Doing as the family plans is a classic bait-and-switch. The questioner doesn’t comprehend that, either.

Then the rationalizations for theft start. “This couple have some needs that aren’t strictly related to the child’s care, like a new car.” “Strictly” is such a wonderful weasel word; it greases slippery slopes so well. Again, “The Ethicist” is forced to explain the obvious: the donors weren’t contributing to a needed car, they were giving to support leukemia treatment. If the family wants a new car, let’s see what that GoFundMe will bring in.

Which of the family’s needs couldn’t be sufficiently linked to the child’s welfare to support a rationalization for using the funds? “Am I rationalizing…?” Of course you’re rationalizing; in fact, I think even this ethically illiterate correspondent knows this is rationalizing, and is just hoping that an ethics authority will validate an unethical calculation. The tell is that she feels it necessary to add that they are only seeking a reliable car, not a Lexus. But come on. “Think of the children!”(Rationalization #58) Isn’t this desperately ill child worth, not just a reliable car, but the most reliable car?

As if any further evidence was needed that this reader of “The Ethicist”—and wouldn’t you think that if she did read the column, she might have picked up just a teeny smidgen of ethical thinking over time?—has no clue at all, we get, “[I]s it germane that they’re not extravagant and extremely honest?”

What is that, some kind of cut-rate version of the King’s Pass? Actually, it is: this is a blatant Rationalization #11A, ”I deserve this!“ or “Just this once!” (The King’s Pass is #11.) The theory is that ordinary, greedy, sneaky people shouldn’t use money intended to save the life of a child to get a new set of wheels, but thrifty, honest, good people deserve a little leeway.

What percentage of the population thinks like this? 25% 50%? 90%?

In his answer, “The Ethicist” does provide an unintended hint regarding how Americans end up thinking this way. Like most academics, he’s a socialist, so he writes, “It is immoral that anyone here has to borrow large sums of money for essential medical treatment, especially for a child….we need to expand the pinpoints of empathy to … light the way toward a country where health care is treated not as a privilege but as a right.” Bad Ethicist. Bad! That’s a false dichotomy, and he knows it, but he’s spouting progressive cant now. Health care is like many other human needs that we have to work and plan for as individuals, and recognize that the vicissitudes of fate sometimes turn against us. If health care is a right, surely a home, sufficient food, an education—heck, why not a graduate-level education?—a satisfying job, guaranteed income, having as many children as one’s fertility allows, child care and transportation also should be “rights.”

Why shouldn’t it be ethical to use other people’s money to get a reliable “reliable” car?