This isn’t about bias, although a good case could be made that bias is at the root of the problem. It is about supposedly experienced political reporters not knowing, understanding or respecting the Declaration of Independence.

Lat week, the Associated Press’s Will Weissert wrote AP’s report on Texas governor Rick Perry’s announcement of his candidacy for President, and included this:

“In a nod to the tea party, he said: ‘Our rights come from God, not from government.'”

This is ignorant, embarrassing, and wrong. He should be sent back to school, fired, or suspended, and so should the editor that let this pass. That our rights (our “inalienable rights”…ring any bells, Will?) come not from government but from God (“their Creator”…Will?), or, if you will, nature, innate humanity, the cosmos, or however you roll, is not the invention of the Tea Party, nor is citing the concept pandering to conservatives. Perry’s statement simply shows that he is familiar with and has proper reverence for the mission statement and founding document of the United States of America, as this AP reporter clearly does not.

Here, Will, you dolt, let me refresh your recollection:

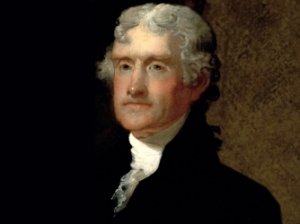

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…”

Got that? Your inexcusable, factually, legally and philosophically mistaken idea that governments grant rights is in direct contradiction with the basis of this nation’s founding, and the Constitution created to enable the mission as stated by Thomas Jefferson and the Continental Congress in 1776. The segments of the news media and the progressive community that make assertions like Weissert’s–call them the Ignorant Left—are arguing for a system in which government dictates what rights we have or don’t have—you know, like the King of England. This is specifically un-American, because it was the exact basis on which the United States declared that being part of the British Empire was intolerable.

Meredith Shiner at Yahoo Politics did the same thing in March, tweeting in reaction to Ted Cruz’s announcement of his candidacy:

“Bizarre to talk about how rights are God-made and not man-made in your speech announcing a POTUS bid? When Constitution was man-made?”

Bizarre, is it, Meredith? Do you live here? Did you attend college, or high school? The Constitution represents the human beings making up a democratic government securing rights that every human being are born with and that may not be taken from him or her. Did you miss class that day when the Declaration of Independence was being taught? Or can you just not read?

Is it God that’s the hang up? I bet it is, since Democrats, progressives and journalists (but I repeat myself) have utter contempt for religion and the concept of God. Well, you badly educated fraud of a “political analyst,” Thomas Jefferson was not exactly Martin Luther. This is why he used the term Creator. Creator—did you miss all of your English classes too? Creator can mean God, as well as designer, builder, designer, inventor, founder…but Jefferson was a terrific writer, and knew that words can mean different things to different people in the same context, so he used a word that also can suggest agency, a beginning, causation, determinant, a catalyst, genesis, inducement, instigation, origin, root or source. Jefferson was also a scientist, and understood more than most–certainty more than you—that we do not have all the answers. What he said, and what the Founders endorsed, and what the Constitution was written to execute and establish for all time, was that human beings have certain rights from the instant they are born, and that no government has to grant them or take them away.

Whatever their flaws, Ted Cruz and Rick Perry understand that, as anyone qualified to seek the Presidency must. Shiner and Weissert do not understand that, and thus are unqualified to vote, much less to be political reporters.

___________________

Pointer: Newsbusters

It’s unalienable. And you are exactly right.

Jefferson, however, wrote inalienable. The official text is the un-.

See?

http://www.ushistory.org/declaration/unalienable.htm

Now that’s interesting.

It’s even alluded to in “1776.” As the debate over the Declaration is almost finished, Dams offers the correction from “in-” to “un-“. Jefferson refuses; Adams says he is correct and that he is a Harvard grad; Jefferson replies that he graduated from William and Mary and won’t yield. The body laughs at Adams’ annoyance, who is heard to mutter, “I’ll speak to the printer about it…”

I don’t know if it was Adams, but somebody did.

I think wyogranny may have been having a bit of fun.

Nope. This is all news to me. I love a good back story. I side with Adams, by the way, as I almost always do. Thanks.

The words are both real, and mean essentially the same thing. If we accept Jefferson as the author (as we now know, the document was a group effort), then I don’t understand why his word choice shouldn’t prevail….at least when we are quoting HIM, as I was, and not just the document itself, which uses un-.

Love the “1776” reference! My wife and I love this musical and are regularly surprised by how few people are familiar with it and the film based on the play. We watch the film faithfully on or around July 4th every year and have introduced dozens of people to it.

As to the errant reporter’s ignorance, I am known to interrupt and correct people who begin statements with “the government gives us the right to…”, and I’m not a Tea Party member by a long shot.

From and article in Real Clear Politics: “It is therefore regrettable—indeed, it is harmful to the public interest—that college education has marginalized study of the Constitution. History departments prefer to dwell on the ways in which the United States has oppressed people on the basis of race, class, and gender. Political science departments specialize in equipping students with the latest methodological techniques for transforming the study of politics into a proper science on the model of physics. The progressive scholars who dominate the nation’s law schools frequently place a transformative political agenda ahead of mastery of constitutional text, structure, and history.”

Sounds as if these journalist kids weren’t asleep in class. Evidently they were paying attention and probably got the best grades.

“with certain unalienable ” I agree with Jefferson, the word is “inalienable”.

“Inalienable” sounds correct to my ear and “unalienable” sounds cumbersome to my ear. But I have no idea why. It may be just 20th Century vs. 18th.

But in either event, aren’t we missing the really significant point here boys and girls? Isn’t the use of “alien” verboten? Aren’t these rights more correctly and justly considered “undocumented rights?”

And shouldn’t any school that teaches the founding documents issue trigger warnings for any students who may find them offensive or unsettling?

You came dangerously close to being put on my keyboard list. I had just swallowed a gulp of coffee when I read this and, had the coffee still been there, my guffaw would surely have soaked the keyboard with it.

Well, after some digging, there’s a suggested rule that it’s based on whether the word is Germanic (un-) or Latin (in-) in origin. Since alien comes from Latin, that would make Jefferson correct, if you buy into that rule. I don’t really think it holds though…

I’m happy with this rule. I always liked Jefferson more than Adams. Adams was obnoxious and disliked, don’t you know.

Unfortunately, sometimes the choice is unambiguous, and it would be untenable to change it. I’m uncertain how frequently it fits, but I will continue to default to it, undaunted.

Each of those un words comes from latin, but there are undoubtedly more which remain undiscovered…

I didn’t try to find germanic words with in- as a prefix.

Yeah, I was just looking for a reason to use the “obnoxious and disliked” line, from the musical. I liked you “Use in a sentence” approach

This is a serious question, and not just a dig.

Given that there had been no King of England within the lifetimes of any of those who wrote that Declaration of Independence, and that this whole thing is bound up with those very issues of identity that were involved (which is why this isn’t a quibble about modern U.S. English), how is this so much worse than writing “King of England”? It may very well be that the journalist was perfectly familiar with that Declaration of Independence but wanted to focus readers’ attention on how this is relevant to today’s interest groups – just as you don’t care about the difference between the U.K. and England now, even though Scots like Flora MacDonald of Bonnie Prince Charlie fame were active Loyalists in those long gone days. It may be a deliberate though knowingly factually unsound choice of wording, just like yours.

I am rather curious where you got the idea that there had been no King of England in the memory of the composers of the Declaration. I suggest a perusal of:

http://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/KingsQueensofBritain/

I would suggest, specifically, the years 1727 through 1820, the Georges II and III.

And, if I may further suggest, this:

http://www.nationalww2museum.org/see-hear/collections/focus-on/kasserine-pass.html

Which will give you some information that you obviously do not have about North Africa during World War II

His point was that “King of England” wasn’t the proper term then and hadn’t been for centuries.

No, it’s only the point of the example. The point is the same as the one JutGory made just after that, that some people – you just there, the journalist in the subject matter – just don’t think factual accuracy is all that important in support of their main thrust. You accused the journalist of ignorance, and I was attempting to show you through your very own example that some people know but just don’t care – even though they know it matters very much to other people’s sense of self and identity (which makes it no quibble regardless of context, on that niggardly principle). In the immortal words of Homer Simpson, “just because I don’t care doesn’t mean I don’t understand”. Just as you excuse yourself your own sloppy usages, you should concede the same to the journalist.

So in other words, you don’t comprehend the difference between a material fact and an immaterial one.

See, a material fact actually changes the point of the statement. An immaterial one doesn’t. Not knowing that the Declaration is the mission statement with which the Constitution has no basis, and that the rights defined in the Constitution limit government power over individuals according to the premise the certain rights always reside with the individual, is a material fact, because it’s literally impossible to understand the limits of government power in the US without it, and omitting it makes all assumptions useless. What King George’s proper title was, on the other hand, is immaterial to the discussion at hand, and the meaning conveyed is exactly the same whether we call him George, Georgie Poo, King George, the King of England, the King of the Britains, or Old King Cole.

Don’t feel bad about being confused about all this. The King of England was confused too.

You’re again illustrating my point. When I reminded you that you don’t think your usage matters (regardless of its offensiveness – it’s material enough that way), you come back with asserting that it doesn’t matter. For some reason you don’t get that the journalist didn’t think his usage mattered. I am asking you to be charitable in your assumptions about him, to consider the possibility that he knew perfectly well but just didn’t care, just like you. Yes, his wording relates to something highly material to you. So? That means you should direct your attention to his values, not to his knowledge, just as I have suggested. You have a target, aim at that and not at the red herring of ignorance.

No, no. The journalists didn’t understand what he or she were saying. The fact that my phrasing was offensive to YOU doesn’t natter one iota…`the objective was not to be pleasing; the objective was to point out political reporters who don’t understand the topic that they write about. That’s material. The label I choose for King George is not. The reporters did not know well, because what they said was materially wrong, and made them appear as ignorant fools, which in fact they are, but which they can ill afford to be. They must care about material facts. The King’s title is not. I don’t care about a pedant of Celtic heritage who flies into a rage at a casual reference to a long dead king. 99.9% knew who I was referring to, and that is all that was necessary. There was no miscommunications at all.

You are being absurd.

Of course, you also don’t understand the topic. The fiction that the Declaration has no force in US law is a factual and historical misconception pushed by limitless government advocates. Journalists, being generally badly and narrowly educated, swallow that myth. They are, in fact, ignorant, and it is, in fact, a big problem.

Careful you are going to set him at quibble factor 10.

Mad King George was technically King of Great Britain and Ireland.

Either title, he lost the colonies and it still chaps some people to this day.

Really don’t care. I have no intention of replying to any other posts of his, and wouldn’t have replied to this one, except for the slur on my father-in-law. Probably was unintentional, but it rubbed me the wrong was. The man had two bronze stars, one in either Africa or Italy and one from Korea. He didn’t talk much about either. Most of what I know about his history I got from his wife and my wife (his daughter). By-the-bye, I agree, being King of Great Britain would automatically include King Of England, unless he was, as you mentioned, quibbling.

I regret that you were offended. I do not regret enquiring into particulars, as such. I do know about U.S. land combat activities in North Africa, including Kasserine, but as I already stated those did not occur across North Africa but only once U.S. forces had reached the borders of Tunisia. As I also already pointed out, none of that is to belittle U.S. efforts, which included those needed to arrange an unopposed advance across North Africa; however, as you didn’t accept that qualification, I thought fit to ask if he had served in a detached role that did have him fighting across North Africa. Think about it: raising the possibility of that is not denying that he did it, it is asking if he did it that way. But nobody – of any nationality or background – fought across North Africa from its western parts to the east in that war.

Where on earth do you get that last sentence from? For what it’s worth, my only personal interest in the matter is that we Celts don’t like being lumped in with, conflated with, England. To venture into ascribing it to revanchism is merely to reach for your nearest handy stereotype.

“we Celts”?

I think “not liking being lumped in with, conflated with, England” is the least of your issues…

Please read what I actually wrote and do not simply use what you think I wrote. I do not mean to offend you by that; I never denied that there was, in England, a king, or that your father in law did not do all the fighting needed of him, only that the details cannot have been such and such (fighting across North Africa with the main U.S. forces, a King of England) but could have been such and such (detached duty, a king involved with my own people) or perhaps something else again. And such details matter.

Sweet sweet tears of sadness over the loss of bloomin’ colonies. It’s odd that those bumpkin colonials still ruffle the feathers of the lobster backs.

What exactly are you crying about now?

You know, we call George C Marshall “General” even though his official title is “General of the Army” or even “Chief of Staff of the United States Army”?

Do you honestly think that “King of England” is insufficient for describing “King of Great Britain and Ireland”? (interestingly enough Great Britain includes, as it’s primary nation: England)

What a doltish thing to quibble.

I’m sure Mad King George didn’t notice the hyper-quibbling distinction either.

Yes – so why jump to the conclusion that there isn’t something else going on?

So King of England is insufficient to describe the man of Germanic origin whose family took over for men/women of English origin, whose families took over for men and women of mixed origins, whose family took over for men French origin, who families subdued the Celts, because it reminds you that there isn’t a pristine pre-civilization dominated by woad warriors and druids anymore?

Readers, from Straw man at wikipedia:-

My substantive objections are mainly on grounds of accuracy, which is why I correct wikipedia’s pre-1707 references back to “King of England” (or whatever) as needed. My personal objections are to the conflation as it does not give people like me our proper standing in the enterprise of the U.K., as well as denying our identity within that – just as it would be unseemly to deny (say) that a Jew in England had his own, distinct sense of identity in which he could properly feel there was value. It has nothing to do with any past conquests, whose reality or otherwise has no bearing on any of that; the Welsh (who were conquered, and were indeed once ruled by the Kings of England, when there were any) can feel it, and so can the Scots (who were not).

For what it’s worth, the Scots conquered the Picts, who were the ones who went in for that woad thing.

I’m not sure you know what a Strawman is, given that the *clarifying question* I asked was not an argument.

*ding ding*

As it goes, your “personal” objections can’t be untangled from their inability to jibe with reality. “Your people” don’t exist as anything other than a diluted bloodline – as ALL ethnicities eventually endure.

I think you are just plain bats on this topic.

You know. Cuckoo.

Jack: “This is ignorant, embarrassing, and wrong.”

I am not sure it is wrong. It might have been a nod to the tea partiers, who, at the risk of over-generalizing, would take the position that the state is there to serve the needs of the individual, not vice versa.

If that is the case, you can’t really say whether the statement is ignorant or embarrassing. He may know full well the context in which the Declaration was written, but not really care. The Progressive movement of the last century has been all about undermining or transforming those antiquated documents that have no relevance to our modern society.

The quote from Meredith Shiner, on the other hand, is certainly all of those things.

-Jut

Cruz is smart, well-educated, knows his Founding documents, and religious. The statement is only fair if there is any reason to think Cruz would have said anything else if the tea party didn’t exits—There isn’t—or if his statement isn’t objectively correct. It is. Thus the implication is unfair and misleading–thus wrong.

Style suggestion:

An actual valuable and legitimate use of Internet snark in this case would be to replace this line: “mission statement and founding document of the United States of America”

With the same line but hyperlinked:

mission statement and founding document of the United States of America

Well, the US Supreme Court sort of sides with them now. They upheld the San Franciso law that states that handguns must be unloaded, locked, and disabled in the home at all times. That includes if someone is trying to break in to kill you. So much for a right to life. Who is obligated to protect your life? The police aren’t. Now, you aren’t allowed to either.

That law applies only in San Francisco. Doesn’t come close in Texas.

The theory was that SF isn’t part of the United States.

I LIKE that…and agree.

Not quite… they just failed to take the case, which is not quite the same as explicitly upholding it. The fact that it’s directly at odds with Heller is more than a little odd, which is why I believe Thomas had a written dissent regarding not taking it.

We do well to remember that the Declaration of Independence is not a philosophical treatise expounding truths about the existence and origin of rights. Instead, it is a political document designed to anger King George (or Georgie Poo, as has been suggested by our esteemed host) and inspire ambivalent colonists to consolidate, revolt, and create a new nation. The Declaration of Independence was very artfully written, and remains an inspiration to people throughout the world. Nonetheless, while it is very effective rhetoric and served its purpose well, it should not be relied upon to reveal truths about God, rights, or anything other than what the founders of our great nation thought would most effectively establish our independence.

I am not aware of any compelling arguments or evidence that rights are natural, God-given, or inalienable. The propositions are assumed by many, but seemingly without evidence. Though I have searched high and low, and far and wide, I have not come across any compelling arguments or evidence demonstrating the truth of claims regarding rights being natural, God-given, or inalienable. I will be grateful to any of you that can provide a compelling argument or evidence that such claims are true. The truth of such claims is certainly not self-evident. On the other hand, there seems to be many compelling arguments refuting such claims.

For example, it is patently untrue that the rights to life and liberty are inalienable. Each and every day, in the United States of America and across the earth, people are deprived of (alienated from) life and liberty. We can maintain that we retain the rights even though we’ve lost the objects to which the rights refer, but we would then have to concede that all dead people have a right to life and that all prisoners have a right to liberty. I am inclined to believe a right that cannot be exercised is nonexistent (for all intents and purposes). (We can still maintain that a person should not be deprived of these rights without due process of law.)

As a Christian, I find it odd that these rights were not mentioned anywhere in the Holy Bible. If they are so important, it seems God would have mentioned them to one or more of the prophets or that Jesus would have broached the subject while he was on earth. Further, I am not aware of any sacred texts from any other religion that mention rights as natural or given by the universe or a super natural being. It is my understanding that the first mention of natural and God-given rights was by John Locke in 1689. It seems unlikely to me that God would give us this great gift of rights, and then proceed to keep it a secret for thousands of years.

Here is a question (asked in three different ways) that may clarify what is at issue: Assuming we have both natural (or God-given) and non-natural (or human-created) rights, what are the elements that enable us to distinguish between the two? In other words, if a person claims to have a natural or God-given right, how can we determine whether or not the claim is true? If I have several rights, how can I know which are natural and which are not?

Unless the answers to these questions are known (as opposed to assumed), we may want to temper reactions to the statements made by Weissert and Shiner. On the other hand, I was not aware that references to God, rights, and the founding documents of our nation were the strict domain of Tea Party members, nor have I ever thought it bizarre for a presidential candidate to quote the Declaration of Independence or Constitution. I would not consider a candidate qualified for the office if he or she could not or would not quote from these documents.

Before I get into a deeper response, you can certainly glean some from the Bible if you must. In a later expose I will add to this, but for now I’m putting kids to bed.

One immediate example that comes to mind:

“Do no murder” taken to a full exegesis would most undoubtedly reveal a “Right to Life”…

Another:

“Do not steal” would reveal a right to private property.

Feel free to contemplate others before I prepare a more full response.

Thank you, texagg04, for this glimpse of a Biblical argument supporting God-given rights. If I understand your suggestion correctly, a command from God for us to behave (or not behave) in some certain way constitutes a right in all others for us to behave (or not behave) in that way. Thus, if I am commanded to not kill, all others have a right to not be killed by me. Alternatively, we might say the right is given previously (pre-existent), and we’re commanded not to kill because it would violate the unstated right.

I think I understand the logic, but it does frighten me a bit. Your choice of commands suggests we have God-given rights to (1) others having no other God than our God, (2) others not making or worshipping images of gods, (3) others not misusing God’s name, (4) others remembering the Sabbath and keeping it holy, (5) being honored by our children, (6) others not committing adultery, (7) others not deceiving us, (8) and others not coveting our property, along with the two rights you mentioned in your reply. Jumping to the New Testament, we could say we have a right to be loved by our neighbors as they love themselves, as well as a right to have others treat us as they would like to be treated.

I am leery of how these rights might be materially asserted, exercised, and enforced. I have read many of your comments on this site. Based on the quality of your thought and writing, I feel it safe to conclude that you are intelligent, sane, and not an ISIS militant. Accordingly, I assume you are willing to exclude some of the rights above listed from being considered God-given. I assume you would also exclude commands to particular persons, such that we have no God-given right for Adam to not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Further, I suspect we might exclude less popular commands such that we have no right to isolate women for a week during menstruation.

If we can exclude some commands from fitness to signify rights, we can conclude that God’s command is not the defining element as to whether something involves a God-given right. This brings us back to my original question. If we have several rights, how can we tell which of them are God-given? What is it about a God-given right that makes it distinct from other rights?

Before I get on with my longer response (which I have yet to start, against my intent):

Here’s the razor:

When considering the man-made construct of an ethical governing system, one would apply the commandments aimed at man’s interactions with man, which would leave out commandments aimed at a particular individuals dealings with himself as well as man’s interactions with God.

So that being understood:

1) Yes you have a right to life.

2) Yes you have a right to your property.

3) Yes you have a right to be respected by your children.

4) Yes you have a right not to be falsely witnessed against.

5) Yes you have a right not have your marital trust violated.

(among others, “…Among these are, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness”)

Last I checked, our laws do protect those rights in so far as they don’t violate the rights of others.

Now, I challenge you to find any religious text, sifting through the various commands that compel how you should treat each other or what you should NOT do to each other, careful to delineate what is a commanded-behavior or a prohibited behavior from a commanded-punishment for violating such, and I’m sure you’ll find incredible agreement.

Having worked through this many years ago, I had forgotten the needed clarification. Thanks for the protest.

Thanks, Otto, for a substantive and provocative post that was fun to read. Also quite mistaken. We can’t remember that the Declaration is not a philosophical treatise expounding truths about the existence and origin of rights, but a political document designed to anger King George, because that’s just not true. One may, as you do, maintain that, but the conclusion flies in the face of history, common sense and logic, as well as self-preservation.

I’m not going to appeal to authority, but I certainly could. There are many, many scholarly works on this issue—I don’t think its even a particularly live controversy—that conclude that the Declaration, was, is and had to be more than just a political document stating grievances. There are a lot of reasons why they reach the conclusion they do, and that I did and have:

1. The document was obviously both. It’s political purpose was to announce to the world, and GB, that the US was withdrawing and establishing its own nation, in order to garner support. Thus it was also a PR document. There is nothing that requires such a work to be just one thing: a statement can chew gum and walk at the same time. Lincoln’s Gettysberg Address was the dedication statement for a cemetery/memorial and a reaffirmation, with key changes, of the Declaration’s mission, which was not essential at the time, but a damn good idea given the context.

2. But it had to be a mission statement as well. You don’t say “we find the current society we are considered part of as human beings so intolerable that we’re leaving” without explaining what you are leaving to, why it is justified, the underlying reasoning, and in what way the new society you are forming will be materially different and preferable. These were extraordinarily smart men, at least the most of them, educated, sophisticated and thoughtful, and were not deluded about the magnitude of their enterprise. It had to be done right, and “We quit, and this is what you’re done to piss us off, you mean old King!” wouldn’t do.

3. A recognition of this was why Jefferson was chosen to write the first draft. He wasn’t, strictly speaking, the best writer in that body, nor the only political philosopher, but his previous statements, essays and treatises involving his interpretation of Locke, Rousseau, Montesquieu and others made him an obvious choice. He was also knee-deep in the creation of a new constitution for Virginia, and had the proper role of governments and rights much on his mind. Plenty of other members were more skilled at fiery political rhetoric, if that was all they wanted.

4. They had to want more, however, because they knew that in establishing not just a new nation but a new organization of any kind, orderly minds begin with a statement, not long, not detailed, about what the organization is being created to do that is distinct from other already existing organizations. You don’t form a nation and afterward say, “now what?” That’s suicide (though, as an organization governance consultant, I do see it, though the founders of such entities are not Jefferson, Adams, Franklin, Hancock and Dickinson.) A primary reason the Declaration is widely accepted as a mission statement by scholars, lawyers and political scientists is that it looks, reads, and sound like one at the beginning, which is where missions belong.

5. Jefferson, among many others, repeatedly referred to the opening assertion in the Declaration as establishing the rational for Republican government, as here, in 1823—

6. The Declaration was also used as a mission statement during the writing of the Constitution, and tacitly acknowledged to be such. The Constitution itself is an enabling document, essentially organizational by-laws. Usually by-laws place the mission up front, but the Constitution does not, it’s short preamble only describes what all governments do, except for “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” That’s a reference to the mission statement—the Declaration. What “blessings”? Jefferson already told us.

7. The slavery issue was immediately recognized as a flaw in the document because a nation with the mission of the US, as defined by Jefferson, could not include slavery. If the document was just a shot across Great Britain’s bow and nothing more, then slaver wouldn’t have been an issue. I’d argue that the Civil War proves that the Declaration was a mission statement, and established human rights distinct from what was granted by government that made slavery a near fatal breach of integrity….and this was understood before the Constitution was even drafted.

7. The issue of rights is pretty much binary, unless you believe that that nobody ever has any rights, in which case laws are just practicalities, and not moored to any principles. Either human beings have basic rights from the moment they are alive, or government bestows rights on them. The former vision is quintessentially American, the latter is statism. Because statists know that the Declaration essentially declares that approach to rights and government intolerable in the U.S., our local breed push the mythology you just did. Only human beings wo are timid, afraid, lacking character, aspirations and confidence are willing, and often eager, to give up self-determination and guaranteed rights to an all-knowing government. This is a profoundly archaic attitude, which is one reason its embrace by so-called “progressives” is damning, and proves that they seek power, not principles.

8. This—“it is patently untrue that the rights to life and liberty are inalienable. Each and every day, in the United States of America and across the earth, people are deprived of (alienated from) life and liberty”—is silly, and your argument would be stronger without it. Jefferson was stating that the rights are inalienable because they never disappear, regardless of government decree or the actions of mankind. He was not talking about individuals—one’s right to freedom can be duly revoked if one sufficiently uses that right to violates the rights of others—but of mankind, directly rejecting the assertion of despots and monarchs that rights are bestowed by them at whim and will. It is a statement of the existence of human rights, not a statement that rights are immune from abuse. In philosophical logic, you committed the masked man fallacy (also known as the intentional fallacy or the epistemic fallacy, an illicit use of Leibniz’s law in debate. (Leibniz’s law states that if one object has a certain property, while another object does not have the same property, the two objects cannot be identical.) I call it restating a proposition in erroneously absurd for so it can be more easily rebutted. Call it what you may, but call it, don’t use it.

9. Jefferson didn’t write that natural rights come from God, and he probably wasn’t a Christian (or a Jew), so the Bible is irrelevant. His assertion is that they are there from birth, which makes sense. The fact that he doesn’t, or couldn’t explain who or what is the creator is also irrelevant. If you want to deny the philosophical position that human beings are born with rights, and that governments exist to protect and ensure those rights rather than to grant them, is up to you.

10. But then I think you live in the wrong country, because this culture, society and government were created with an acceptance of natural rights at their core.

Thank you, Jack, for the thorough and beautifully written response. I agree that the Declaration of Independence is the foundational document and mission statement of our nation. It would be silly to argue otherwise. I also agree with most everything else you included in your reply. I still maintain that it is a political document rather than “a philosophical treatise expounding truths about the existence and origin of rights”. The Declaration of Independence provides detailed reasons, demonstrating and explaining well, why the United States of America should be independent of Great Britain. It is a powerful document, but it explains (expounds) very little about the existence and origin of rights. We are told that we are endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights, but we are not given any reasons why we should believe this is true.

I could use some clarification with respect to your paragraph numbered eight. I think I understand the fallacy, but I am not clear on how I used it. My brother alive and my brother dead are both my brother (i.e., the same) even though they are clearly not identical. In my example, what is my father and what is the masked man?

The same paragraph did reveal more about how our views on rights may differ. Your view seems to lean toward the metaphysical. Perhaps it is similar to how a Hindu might view karma – a mystical attribute of the universe that exists and operates whether or not we accept it, and whether or not we are aware of it. It seems such rights would exist regardless of whether we are alive or dead or comatose or existent. My view is more material and earthly.

Still, none of the above gets to the heart of the issue. Asking my question in less abstract terms may help. Suppose some slick politician comes along and claims we all have a natural right to health insurance, even if someone else has to pay for it. How can we know he is telling the truth, that it really is a natural right?

If we cannot identify the element(s) that make a right natural rather than of human origin, our only reasons for believing any particular right is natural are: (1) we want to believe it is a natural right; and (2) a lot of other people have believed it is a natural right. Neither of these are particularly good reasons.