This essay is closely related to yesterday’s post about the elderly defense lawyer who revealed in a memoir shortly before his death that the client he successfully defended against kidnapping charges in his most celebrated case was guilty. One commenter opined that it is unethical for a lawyer to defend a client whom the lawyer knows is guilty, which immediately reminded me to republish my explanation of this core element of legal ethics and the criminal justice from 2005. The commenter’s position is surprisingly common, even among law students. I’d bet that a majority of the American public is confused about the issue. That is more than a little scary, but it explains why, for example, the public was so blase about Derek Chauvin being convicted of murder under conditions that made fair trial virtually impossible. What follows is very slightly edited from the original version, which can be found here.

***

How can it be right for an attorney to defend in court an individual that he or she knows is guilty? The fact that so many Americans are perplexed by this after two centuries is an indictment of the legal profession, which has flunked its obligation to protect its role in protecting a crucial Constitutional right by making sure that it is understood by the pubic that right serves. About 20 years ago, then-Fox TV commentator Bill O’Reilly led a campaign to get California criminal lawyer Jeffrey Feldman disbarred because leaked plea bargaining sessions showed that he knew his client, child killer David Westerfield, was guilty of murder, even though Feldman was vigorously disputing his guilt in court. O’Reilly pronounced Feldman a liar. He was wrong, but his ignorance, in this matter at least, is excusable, but only because it so widespread.

To understand the criminal lawyer’s ethical responsibilities, begin with this: the Founders of the American republic believed that citizens in a fair and just society shouldn’t be imprisoned or punished just because the government decides they are guilty of something, whether it is murder, robbery, not paying taxes or, as with John Hancock and Samuel Adams, criticizing those in power. They wisely decided on a system that required the government to prove that an individual had committed a crime to the satisfaction of an unbiased jury. Not only that: they decided that a very high standard should be applied in determining legal guilt: “beyond a reasonable doubt,” or near certainty.

Why? Taking the cue from British legal scholar William Blackstone, who famously said that it was better to have ten criminals escape punishment than to have one innocent man imprisoned, uber-Founding Father Benjamin Franklin said that “ it is better one hundred guilty Persons should escape than that one innocent Person should suffer.” Achieving this ideal means keeping the government honest: no convictions based on false or planted evidence, unreliable or lying witnesses, or confessions extracted from the accused by torture, beatings, or other forms of duress even if the accused is, in fact guilty. All of that is essential for the system to work, if to work means “being fair and just.” If we permit the government to cheat in order to imprison a guilty individual, we have no way to stop it from cheating to imprison an innocent one. Indeed, it will be impossible to tell the difference.

So regardless of whether a criminal lawyer’s client is guilty of the crime he or she is being tried for or wrongly accused of committing, the defense attorney’s job doesn’t change. It is to make the prosecution prove its case with sound arguments, real evidence, and reliable testimony. In a sense, the real client of a defense attorney isn’t truly the criminal defendant at all but the integrity of democracy and the justice system. For example, O’Reilly was incensed that Feldman, while defending Westerfield, argued to the jury that the state’s evidence suggested that certain persons other than his client may have killed the victim. “That’s a lie!” Bill fumed. But it wasn’t a lie: Feldman’s argument was absolutely correct. The evidence in question didn’t rule out other suspects. The jury would be making its decision based on false reasoning if it took the prosecution’s word that the evidence only implicated Westerfield. Feldman was meeting his ethical duty to point out to the jury that the prosecution’s argument was not as conclusive as it claimed. Again, the lawyer’s job was to make the prosecution prove its case.

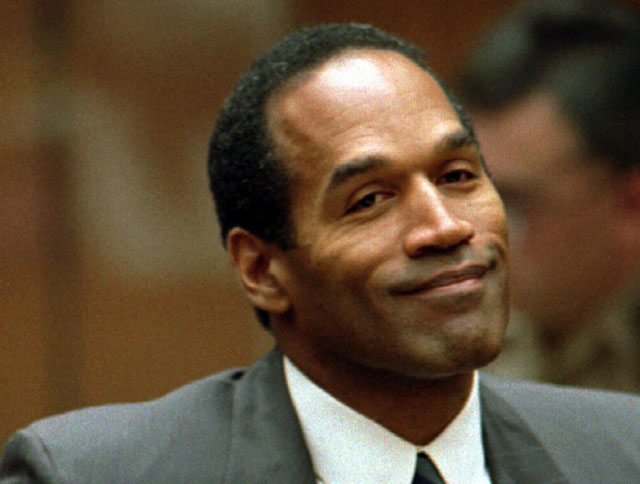

Feldman did his job, and the prosecution and jury did theirs: David Westerfield was convicted. But what about the equally guilty O.J. Simpson, who was, infamously, acquitted? If the late Johnny Cochran and the rest of O.J.’s legal team knew he was guilty, didn’t they knowingly perpetrate a terrible miscarriage of justice? Didn’t they willingly let a double murderer loose on the golf courses of Florida and California? How can that be ethical?

Of course, we don’t know if Simpson’s lawyers “knew” he was guilty, though there is evidence that some or all of them strongly suspected as much. Many defense attorneys don’t want to know, because knowing can make it harder for them to do their jobs. It can be difficult to point out flaws in the prosecution’s arguments if you are hoping that the prosecution puts on a slam dunk case and the homicidal monster sitting next to you gets locked up for good. Many defense lawyers set out to convince themselves of a defendant’s innocence, no matter how unlikely, because such a mindset helps them make sure that they won’t subconsciously do a sub-par job out of sympathy for the victims or revulsion for their client. Those who know their client is guilty have to keep reminding themselves what their duty is and why it’s so important.

But even assuming that the Simpson legal team was certain that O.J. hacked Nicole Simpson and Ron Brown to death, they had reason to sleep soundly on the night after the acquittal. They held up their end of the Constitutional directive. They ensured O.J. a fair trial, which every American from Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer to Michael Jackson and Martha Stewart to you and I, must have before the government takes away our freedom. In the O.J. Simpson case the prosecution was amateurish, the police were inept, the judge was unable to control the trial, and the jury simply didn’t have the ability to follow a lengthy trial that had too much evidence and too many witnesses. Perhaps most crucial of all, the case featured a defendant that the jurors thought they knew because he was a celebrity. Arguably every component of the Simpson trial except the defense performed badly. Some aspects of the trial might support arguments for reform, but the failings of the rest are not the fault or the responsibility of Simpson’s defense attorneys.

Criminal defense attorneys have an unimaginably difficult task, as stressful and emotionally challenging as that of a surgeon who must hold life in his hands. It doesn’t produce satisfaction or joy when defense attorneys see their guilty criminal clients go free, guaranteed by the Constitutional prohibition against “double jeopardy” never to have to suffer any punishment for terrible crimes. But unless defense attorneys do their jobs well enough that this can happen when the prosecution or jury don’t perform their jobs well, democracy dies. Individuals accused of crimes become helpless, completely dependent on the good faith and competence of police and prosecutors for their fate. The individual, guilty or guiltless, becomes powerless. The Founders’ dream is betrayed.

Many attorneys can’t handle the complex ethical balancing that criminal defense work requires. I left the field because I couldn’t. But they are not the villains of the American justice system; they are its ethics heroes. Their zeal in making sure that citizens lose their freedom only when there is strong evidence to justify it protects all of us, and we owe them our gratitude, and perhaps, some day, our lives.

Great post. I will not be so forgiving to O’Reilly. He reminds us that before he became a TV pundit he taught History; as did my father. The Franklin quote was taught to me early as a child so Bill should be aware of this rudimentary concept of proving guilt

That’s a stellar piece of honest ethical analysis, Jack. I really enjoyed reading it, and it was spot on.

It’s a shame the “only the outcome matters” left and the “law and order” right can’t follow that reasoning. Even if they were willing, the would (and continue to) construct emotional, logically bankrupt arguments to oppose it.

I’m really glad to see a near-bulletproof defense of criminal defense attorneys. Let the opponents suck on it. I hope it puckers their appeals-to-emotion mouths to the point they become a point singularity.

Wonderful essay, Jack. I’ll be saving the link to this one.

RE: OJ Simpson: After he was disbarred, F. Lee Bailey moved to Maine, and by happenstance became a great friend of an ex-radio colleague (who was also a trial lawyer, and a successful one, though not in criminal defense). I met Bailey a few times. Interesting man. It may have been self-delusion borne of professional responsibility, or a personal defense mechanism, but even many years later he was absolutely certain that OJ was innocent.

Curious, that.

Bailey had an image to protect, and it was always the “champion of the wrongly accused.” So he had to say that.

Except he was disbarred, with slim chance of reinstatement. I hear your point, but in asking him about it – and I had no power over his reinstatement – I got the sense he believed it.

It could have been practice for a more skeptical audience, I’ll admit. But for whatever it’s worth, our mutual friend – no dummy he – was also convinced that F. Lee believed it.

All the more reason to guard his reputation and legend. He was a smart guy, and I don’t see how any smart guy could reconcile the evidence, OJ’s narcissism and misogyny, the DNA, the location of the blood, the shoe prints with his claims of innocence.

Oh, I don’t disagree. I thought OJ was guilty as hell, and that F. Lee was nuts.

As regards your other response: I think it’s important to remember that the understanding of the average American with regard to the role of the defense attorney was probably created by Gregory Peck portraying Atticus Finch, Raymond Burr as Perry Mason, and subsequently burnished by countless tele-novellas representing defense attorneys as saviors of the screwed.

Most of this nation’s understanding of jurisprudence was delivered in one-hour doses, inclucing 22 minutes of commercials. Can’t blame the lawyers for that.

But I do. The ABA has a duty to address the misinformation, and could. It WANTS the public confused.

That’s a fair point.

How does the ABA benefit from public confusion regarding the ethics of being a defense attorney? I forget if that’s come up before.

One reason is that lawyers and their clients benefit from having jurors think they are something that they are not. Law still operates under what was called “The Standard Conception<" which means that lawyers accept and advocate for their clients' needs and beliefs, even if they personally disagree with them,disbelieve them, or find them repugnant. If the was in jurors' heads during trials, lawyers would be far less persuasive. In reality, their outrage is usually fake, their certitude is exaggerated, their emotion is a performance, and that's because they are hired to be stand-ins for normal people who would be lost in our system without them. That's an important role in democracy, but it's not what the pubic thinks lawyers do: seek justice, right wrongs, etc. Lawyers want to be thought of that way, but that's not their true role. Their role is to give citizens access to the law, for good or ill, and lawyers, most of the time, don't care which. It's not their place to care.

My only question boils down to semantics. Take the case you described yesterday. To me, it’s perfectly reasonable to say, “here we have a witness who was in a position to know, and he claims there was no kidnapping,” but to assert “there was no kidnapping” is not suggesting the prosecution hasn’t proved its case beyond reasonable doubt; it’s lying (assuming he knew there really was a kidnapping, and the Times article says as much). To me, outright prevarication has crossed the line from vigorous advocacy to something really problematic.

Are there really no constraints other than suborning perjury?

Well, what about “my client is innocent!”? The argument that the police planted evidence on OJ, in his car, in his home, before they even knew that he didn’t have an iron clad alibi, was absurd on its face, and they knew it. Cochran made the argument anyway. A lawyer’s statement isn’t evidence. Testimony is. So all DeBlasio was saying, in legal ethics terms, was [You heard the testimony of Lynch] There was no kidnapping [If you believe what he said under oath.] He doesn’t have to speak the equivocations, and it’s bad practice to cast any doubt when your client is relaying on one slim reed.

That’s fine as a legal argument. But many jurors don’t know that “a lawyer’s statement isn’t evidence. Testimony is.” The more perspicacious ones know they’re watching a performance from defense counsel. Most, however, think (incorrectly) that “they couldn’t say that if it weren’t true,” or at least if they knew it to be untrue. And that presents a real problem.

Big problem. Public ignorance regarding the justice system and what lawyers do is a result of negligence in civic education and the legal profession itself. Being a trial lawyer has much in common with being an actor. One thing is that neither are speaking for themselves, and what they believe isn’t important.

I became a law enforcement officer while still an undergrad, fully intending to go on to law school and then become a highly-paid labor-relations-lawyer. A year later I took a vow of poverty and chose law enforcement as my career, which lasted more than forty years. I was familiar with the “better that a hundred guilty men go free” idea since high school Civics class, and understood the importance of it.

Although I never grew to like the fact that a lot of the guilty escaped their just punishments because of the way our system works, I always took comfort in the knowledge that the same protections applied to me. and I became more determined to conduct better investigations, compile more evidence, obtain solid confessions through good interrogation techniques and generally prepare better cases. I developed some expertise in Fourth Amendment law and even today I continue to follow court cases where verdicts and appeals hinge on search and seizure law. I learned at the feet of many good officers, supervisors, prosecutors, judges and yes, even a few defense attorneys who would tell me (post-trial) how to avoid repeating mistakes they had exploited (if it wasn’t already obvious to me at that point).

My greatest frustration over the years was not defense attorneys but juries. One lawyer friend calls it “trial by twelve people too dumb to get out of jury duty,” and in many instances that seemed to be true. In numerous cases I encountered juries that seemed unable to comprehend either the law or the facts. In later years prosecutions labored under the “CSI Effect,” with juries expecting to be dazzled with DNA, fiber, ballistic, blood spatter and other types of scientific forensic evidence at every trial, and often looking askance at any case where it was absent. I had little respect for lawyers who practiced the “pound the table” method when neither the law nor the facts favored their client, nor for those few judges who allowed foolishness by attorneys (or anyone else) to persist in their courtrooms.

I have known several judges over the years who did a superb job of educating jurors and the courtroom spectators about the roles of various actors in the justice system and explaining the trial process. Of course, I’m also old enough to remember when Civics was a required high school class.

I’ve been away for the weekend, but am SO glad I scrolled down far enough to read this. Outstanding!! I have had conversations on this topic on numerous occasions, and have tried to explain the purpose of defense lawyers. My explanations far FALL short of this, so I’ll just point to this in the future.

Thanks so much!!