I was certain that Ethics Alarms had explored the problem of estates issuing, publishing and otherwise profiting from famous artists’ works when the artists have specifically said that the works involved were to be withheld from the public. It has not, however. I suppose the issue is ripe for an ethics quiz. However, as this is an issue that has always intrigued me, I’m going to use a current controversy to delve into the matter now.

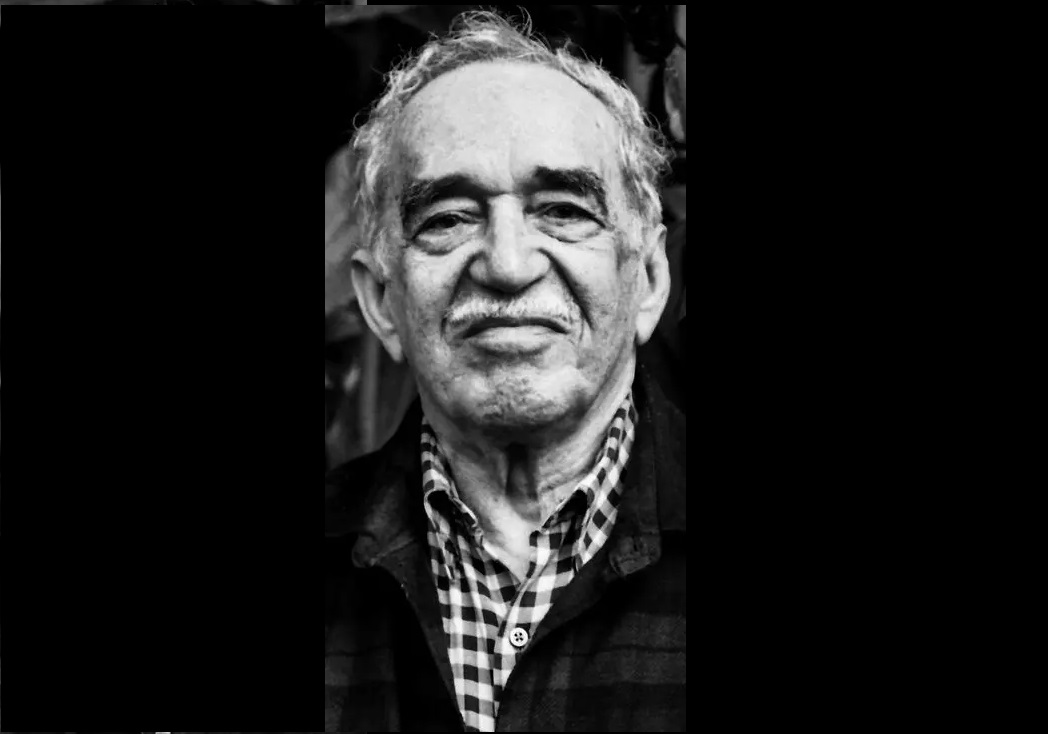

Gabriel García Márquez (of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” fame, among other works) labored on a final novel in his last years. After five versions and constant edits, additions and deletions, he gave up. He ordered his son to destroy all versions of “Until August” upon his death. That occurred in 2014, but the novel was not destroyed as he requested. All the drafts, notes and fragments were deposited at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, in its Gabriel García Márquez archives. Now Márquez’s sons are defying their father’s wishes further and having the novel published this month. Because the author is a major international literary figure, the “new” work is considered to be a major publishing event.

But is it ethical to publish the novel at all, if 1) it wasn’t finished 2) its creator decided it wasn’t up to his standards, 3) the work risks diminishing the author’s reputation, and 4) the artist specifically directed that it be destroyed?

There just aren’t any clear rules for this problem. Whose interests take precedence, the creator of work of art, or the public and future generations that might benefit from it?

The sons now argue that “Until August” is a valuable addition to their father’s body of work, but of course that would be their public position. Maybe it is their real motivation, or maybe they are short of cash or in debt to a drug cartel.

The New York Times recounts past examples where an author’s explicit directions were defied with a subsequent benefit to literature:

“On his deathbed, the poet Virgil asked for the manuscript of his epic poem “The Aeneid” to be destroyed, according to classical lore. When Franz Kafka was gravely ill from tuberculosis, he instructed his friend and executor, Max Brod, to burn all of his work. Brod betrayed him, delivering surrealist masterpieces like “The Trial,” “The Castle” and “Amerika.” Vladimir Nabokov directed his family to destroy his final novel, “The Original of Laura,” but more than 30 years after the author’s death, his son released the unfinished text, which Nabokov had sketched out on index cards.“

The closest Ethics Alarms got to this issue was when the estate of Harper Lee browbeat the aged and cognitively declining author into agreeing to have the prequel/sequel to “To Kill a Mockingbird” published after decades of refusing. The book muddled the image of fictional legal icon Atticus Finch and gave ammunition to critics of Lee’s classic—both originally reasons why she had wanted the manuscript to stay unpublished. I wrote, “It would be foolish, as well as unfair and wrong, to allow an early, unheroic version of Atticus Finch, previously discarded by its author and suddenly resuscitated in her dotage for someone’s monetary gain, to erode the cultural value of the hero and the icon who share his name.”

As with so many ethics problems, there are confounding details involving “Before August.”

At one point Márquez sent a draft of “Before August” to his literary agent. By 2012, however, when he decided that the manuscript should be destroyed, he was in the midst of galloping dementia. He had difficulty even carrying on a conversation, and was losing his memory.

“Gabo lost the ability to judge the book,” Rodrigo García, the eldest of his two sons, told the Times. Rationalization? Perhaps. But it was still “Gabo’s” book to judge.

I am torn on this issue. Pulling me to the side of abiding by the artist’s wishes is my conclusion in this post, about the so-called “last song” by The Beatles, a never completed John Lennon composition of moderate worth that Yoko Ono allowed the surviving Beatles to overdub and digitally enhance. “I detest spoiled exits,” I wrote. “They are self-inflicted wounds that hurt others as well, the inevitable product of hubris, ego, and a juvenile unwillingness to accept reality.” Yet most exits are messy and far from perfect.( Ugh—there’s Grace again, and I thought this post was far enough removed from her death to keep me safe…) Once an artist passes into the Big Hall of Fame in the Sky, he or she “belongs to the Ages,” as Edwin Stanton said of Lincoln when he died. Whatever remains behind is no longer the artist’s possessions, but history, insight into the art and artist, and, just possibly, cultural treasure.

Reluctantly, I come down on the side of the Márquez sons and their decision to publish the novel, whatever their motivations may be. And artists should be warned: if you really don’t want your creations to be revealed to the world, destroy them while you can.

For there to be a true ethical dilemma, there must be conflicting harms.

I don’t see the conflict here.

On one side, the betrayal of a trust and a promise to a deceased parent for personal gain. On the other, the potential of withholding forever a work of literature. Which do you have trouble appreciating?

On one side, the betrayal of a trust and a promise to a deceased parent for personal gain.

That side does not exist — there is no possible harm that can be done to Gabriel Marquez, and the degree of personal gain is irrelevant.

Real world example. When my brother came out of the closet, my mother wrote him out of her will. I was the executor. Agreeing to be the executor imposes an obligation to carry out the terms of the will. After she passed, if I gave half the estate to my brother, did I betray a trust and a promise to her?

You’re taking the position that breaching a trust and committing a lie aren’t unethical unless someone is measurably harmed. The culture is harmed when you do these things. YOU are harmed. Promises don’t expire when the beneficiary of them does. Thus lawyers can’t breach a confidence of a dead client. This is basic Golden Rule stuff. I agree that the other side of the author ethics conflict should prevail, but the weaker side is still substantive.

No, I’m taking the position that a promise made expires when the person with whom the promise was made dies.

Otherwise, I breached a trust and committed a lie when I gave half my mother’s estate to my brother, right?

No, I’m taking the position that a promise made expires when the person with whom the promise was made dies.

But again, the law does not agree with that position. Nor, in most systems, does ethics. Yes, a promise to a dead party is unlikely to be enforced, but as Yul Brenner says in The Magnificent Seven, those are exactly the kind of promises that have to be kept.

Such thinking would invalidate every element of a will. If the executor could do this then he or she could appropriate any and all resources for his or her own benefit

You did breach the trust. Having good motives doesn’t change the act.

I don’t think it would be unethical if you took your brother’s portion out of your own share, AFTER you divided the assets in your official capacity as executor.

I was the only other inheritor.

But your comment makes the ethics involved very situational IF ethics are involved.

No. Nothing situational about it. Once you have followed through on the duty as executor to divide the estate as the decedent directed, you can do what you want with the part of the estate that is now yours. The situation Gamereg described is essentially this—which you commented on.

Of course you did. It’s a clear ethical breach and a breach of trust. It can be justified ethically under extreme utilitarianism, but fails miserably under most other ethical system. Would such conduct work as a norm, universally applied. No. Wills could be relied upon by anyone. An executor could do whatever he or she thought was “best” with the assets. That’s why beneficiaries of a will can sue executors for not following the will.

I saw the story yesterday, and I was hoping you’d comment.

To me, the key consideration is the dementia. If Márquez was corpus mentis at the time he demanded the manuscript be destroyed, I’d be on the other side of the issue. But I remember my father’s delirium in his last days. One particular delusion was that a group of students had sneaked into the basement of his house and were just waiting for him to die to take over the entire property. I told him there was no one there, but he was adamant. I assured him I’d go down there and make sure as soon as I got back to the house. Needless to say, I didn’t. I don’t regret the lie.

Side note: It’s t-shirt weather for retirees in East Texas, and the one on the top of the pile in my drawer was from a production I did a few years ago of Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck. About the only thing we can say with certainty about the text is that any choice we make is likely to be contrary to the author’s wishes. Not quite the same ethical questions, but close enough to elicit a wry smile at the way the universe is so arranged.

But again, the law does not agree with that position. Nor, in most systems, does ethics.

You have lost me here — but I am neither a lawyer nor an ethicist, so that is no big challenge.

It doesn’t seem the law has a vote here. Unless there was some contract, and an injured party, then this is outside legal purview.

And it seems equally distant from ethics. Near as I can tell, the only reason ethics as a system of thought exists is to ascertain relative degrees of injury or gain in order to assess a value judgment to decisions. With all due respect to Yul Brenner, what matters about promises made to the dead is their content, not the making of them.

Which is why I raise my real world situation: the fact pattern is identical — a promise made to allocate her estate as she directed. To which you would say “Ah hah, you just trashed your own argument!”

Not so. Assume the opposite case. As executor of the estate, I don’t give my brother the 50% of the estate. He is an injured party, with specific property rights that I violated: I have committed theft.

But my deceased mother has no property rights, including no right to any promise I may have made. There is no injury to her, and should I turn around and give half of her estate to my brother, certainly no injury to him.

As far as publishing the novel goes, its completeness, his standards, and reputation have no moral content. Gabriel Marquez is beyond all of them. The promise, therefore, is empty. Let’s say that the Marquez brothers devote all the profits from publishing to an orphanage, does that change the ethics at all?

Oddly, despite having re-read your post many times, I just noticed this: He ordered his son to destroy all versions of “Until August” upon his death.

So, no promises broken?

I noted that the brothers broke their promise to their father from the get-go.

The word “promise” appears nowhere in the original post.

However, the words “ordered”, “requested”, and “wishes” do. His sons have no ethical obligation to obey their father’s orders, requests, or wishes, posthumously or otherwise.

But even if there was a promise involved, it is a nullity once their father passed. Such a hypothetical promise was made to their father, not to society at large. Should everyone start betraying such promises, there is no slippery slope to be had, because an essential element of such a betrayal is that there is no possibility of harming the person to whom the promise was made, or anyone else, for that matter.

This isn’t a matter of a will or trust, as there is no contested property right. I brought up my situation because it has an identical fact pattern. If my conduct was not unethical, the the Marquez brothers’ isn’t, either.

Or, if it was unethical, that needs some explaining, because I can’t see it.

Yup, I’m going to do a post on the macro issue as soon as I can clear the decks. Thanks for raising it—I’m sure others share your concerns.

✅