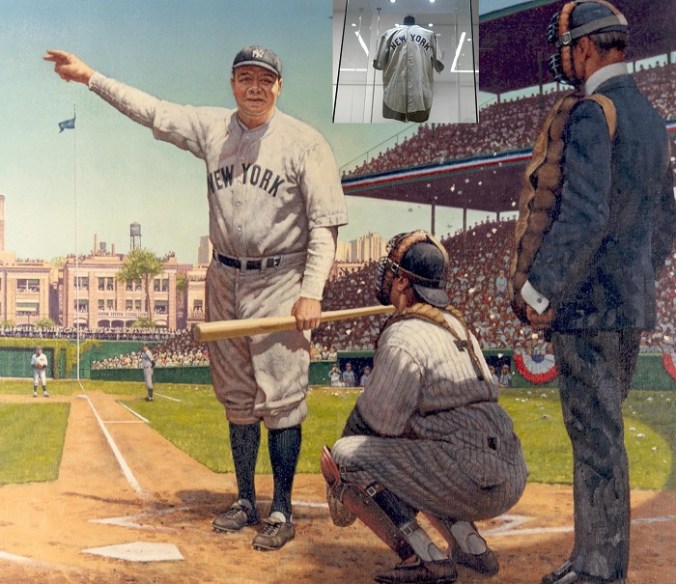

The jersey worn by baseball legend Babe Ruth when he “called his shot” in Game 3 of the 1932 World Series sold over the weekend for $24.12 million, setting the auction record for most expensive sports collectible. The previous record price for any sports collectible was the $12.6 million that a rare mint condition Topps 1952 Mickey Mantle card fetched in 2022. Babe’s jersey far eclipsed the $10.1 million a Michael Jordan Chicago Bulls jersey from Game 1 of the 1998 NBA Finals achived at auction that same year, the record for athletic attire until Babe broke it, like he shattered so many records when he was alive.

The sale raises many ethics issues, but the main one is that the exorbitant price is almost certainly based on a fabrication, a lie. It is similar to paying millions for the axe little George Washington used to cut down his father’s cherry tree.

There has been astounding amount of ink spilled over this legend over the decades, and it qualifies as a genuine historical controversy, but, in my view, just barely. Here is as good as an analysis as you are likely to find, an article by “MLB Mythbusters” titled, “True or false? The Babe called his shot: Let’s see if we can settle this.” As someone who has spent an inexcusable amount of precious time in his pointless life watching, reading about and thinking about baseball, I was aware of almost everything mentioned in the piece except this: there is an equivalent of the Zapruder film of the key moment, and the article shows it. The film is grainy and ambiguous, creating a veritable playground for confirmation bias, but nonetheless, it is the first substantive, non-hearsay evidence I have ever seen that the Babe did something provocative before he hit that famous home run.

So here is what we have:

- Let’s put aside the obligatory “How can someone pay $24 million for an old piece of cloth while children are dying in Gaza?” or similar bitches. Human beings have the right to spend their money on what they want to spend it on, and it’s not unethical for them not to spend it on what you would spend it on (or what you claim you would spend it on if you had such resources, which makes the complaint intellectually dishonest, since your claim is almost certainly never going to be tested.) Moreover, the jersey is an investment. Sure, its perceived value could fall, but that’s unlikely. More likely is that the owner or his estate will be able to sell the jersey later and fund a free speech organization, if that’s what they choose to do.

- The ethical way to justify the sale is this way: the jersey is the only piece of memorabilia confirmed to be involved in one of the most famous sports controversies and legends of all time. That makes it a valuable historical artifact. Calling it the jersey Babe Ruth wore when he “called his shot” in the 1932 World Series embraces what is almost certainly a falsehood, deception, exaggeration, something.

- If Donald Trump made the equivalent claim, it would definitely be categorized as a lie by our news media.

- Read the article, but for me, the conclusive fact has always been that Ruth himself, despite his bombastic personality that was almost completely devoid of modesty, initially denied that he pointed to centerfield to show Cubs pitcher Charley Root that he would hit the next pitch over the wall. It was only after the story became part of baseball (and Babe Ruth lore) that he endorsed the story himself.

- Ethics Alarms has examined the phenomenon of “Print the legend” many times; there is a tag for the concept, and the beneficiaries range from Martin Luther King to JFK to Mike Brown to Jim Bowie, Davy Crockett and their fellow heroes at the Alamo. You can find those essays (and others) here.

- The story of Babe Ruth calling his shot is as good an example of the “Print the legend” principle as there is, maybe even better than the one that defined the phrase, the irony at the heart of John Ford’s classic, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. The Mythbusters analysis defaults to it, concluding,

….where do we stand? Did Babe Ruth call his shot, or didn’t he?

The verdict: He did, just maybe not in the way we usually imagine it. It seems safe to say that, if Ruth really had pointed his bat out to dead center field and then immediately parked a baseball there, the contemporaneous reporting (not to mention the Babe’s ensuing response) would’ve been more consistent; it’s awfully hard to believe that anyone in the press box would’ve missed it, and that Ruth would’ve been so coy until later on.

But we know that there was plenty of jawing back and forth, everyone seems to agree that Ruth was counting strikes, and the video pretty clearly shows that something was about to happen on that next pitch. So the most likely answer is a bit of both: No, Ruth didn’t precisely predict his homer, but he did stride up to the plate, fans and opponents jeering at him, and tell the world “hey, watch this.” Which is still 1) sort of calling his shot and 2) most important, an absolutely incredible flex, the sort of thing that kids will try to emulate for decades afterward. Because, like any good myth, believing in the story is way more fun.

Ugh.

Because the whole point of history is that it be “fun.”

I’m pretty much convinced there is a collector gene. Collectors are a breed apart. Fortunately for them, there are enough of them to generate sufficient numbers of buyers and sellers most of the time.

Collecting is a whole world to itself. Let’s look at cars. Some cars are automatic collector’s items. Let’s look at how that works. When a Ferrari special edition comes out, it is and instant collector’s item, even before it is sold. They claim super-low production values and charge multi-million dollars for the privilege of owning it. In return, you get an asset virtually guaranteed to increase in value. Lets look at the questionable ethic of this.

(1) Low production values. It is widely believed that Ferrari and other manufacturers make more than the numbers they claim. Only 499 LaFerrari’s were claimed to have been made, but conservative estimates are that at least 550 were produced. Even allowing for the press cars (which don’t count), the replacement cars (to replaced wrecked ones), and the special gift ones, they made more than 499. However, no one wants to say anything. The people who own them don’t want this known or the value of their car will be reduced. People who want to get a Ferrari later don’t want to get blackballed.

(2) Outrageous Maintenance. Some manufacturers require extensive maintenance to be performed at their dealership or you will lose support. A $5 million car that can never be fixed will lose a lot of value. The MacLaren F1, for example, requires you to pay to rent a racetrack (the whole racetrack) for an afternoon to balance the tires. You were required to put new tires on it at least every 5 years at a cost exceeding $50,000.

(3) Buying a Ferrari. You can’t just buy a Ferrari in many cases. You have to be ‘allowed’ to buy one or ‘invited’ to purchase one. To buy a higher-end Ferrari, you may be told that you have to buy some low-end and perhaps used Ferraris from the Ferrari dealiership before you will be allowed to buy the car you want. You won’t be ‘invited’ to buy a car like a LeFerrari unless you have purchased millions of dollars of Ferraris and you probably need to be famous.

(4) Blackballing. The automotive journalist Chris Harris reported on the lengths Ferrari goes to to optimize their cars for reviews to optimize their performance. As a result, he was blacklisted from getting press cars and banned from ever buying a new Ferrari. It is rumored that anyone selling a used Ferrari to Harris will also be blackballed.

In this type of collector’s market, the Babe Ruth jersey doesn’t even register on the ethics warning scale.

That’s fascinating, Michael. What a racket. And hey, “That’s Italian!”

Steinway pianos are wonderful, but I also think “Steinway” is probably the most valuable tradename in the world. They build great pianos, but they also invented so much in marketing. They are the Cadillac of pianos, or certainly of tradenames! (Speaking of valuable tradenames!)

Car collectors are a subspecies of the collector genus. I love driving my 2017 VW GTI with 130K miles on it and keeping up with an AMG Mercedes in traffic. Of course. Where else do we ever drive our cars?

A great car collector story: Probably more than ten years ago I was watching the broadcast of a vintage “car race” at Laguna Seca. Hilariously, Sterling Moss was driving a car and actually racing against the other cars on the, you know, racetrack. And he was trying to, you know, win the race? He made a bold passing attempt and ended up T-boning another collectible with the collectible he was piloting. The announcers were in shock. Guess old Sterling didn’t get the memo. Hah!

By the way, Yamaha pianos does a similar thing. They call pianos that were brought into the U.S. other than via their dealers “gray market” pianos. They put out a bunch of baloney that Yamaha pianos are specially cured for various markets and “gray market” pianos’ sound boards will crack! Hah! What a bunch of baloney.

I don’t see anything unethical about selling a legend, as long as the article in question (in this case, the jersey) is verified as authentic. If Babe Ruth was wearing this jersey during the game when some say he called his shot, while others say he did not, then whether or not he actually did does not matter: This jersey was part of an event which has gone down in sports lore and is therefore worth whatever value someone is willing to pay. The fact that the event is in dispute may make it MORE valuable, and will probably be part of the story that the collector tells when he/she shows it to guests.

What would make this unethical is 1. If the authenticity was unverifiable or 2. If the price were fixed instead of being the result of an auction.

To use your example of The Alamo, if Davy Crockett’s flintlock rifle used at the Alamo (let’s assume it is verified as authentic) came up for auction, would the price fluctuate based on whether he died during the storming of the Alamo, or (as is likely) he was executed immediately after the battle? I doubt it, mainly because it was carried by the man at an event that has gone down in American Folklore. No matter the truth, it is the object, the man and the legend that gives it value. As long as the buyer knows that the fact is in dispute, but that the object is not, I see nothing unethical in the sale or the amount paid.

I tend to agree with you on this one. “Print the legend” is not great history but it is the lore that most remember anyway.

jvb