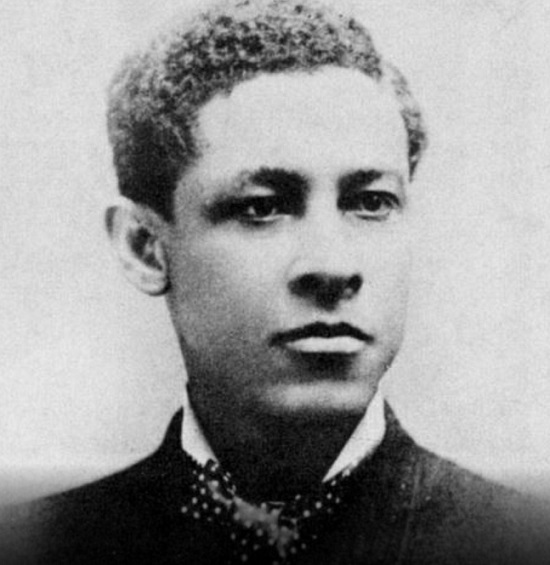

This kind of thing drives me crazy, as regular and long-time readers here know. The culture and society lose so much when important events, figures and trailblazers are gradually lost—forgotten, ignored, erased by ignorance and apathy. That this remarkable and important inventor somehow fell into the memory hole of American history is particularly galling because he was black, and black activists have gone to extreme lengths, at times manufacturing significant black historical figures out of otherwise marginal accomplishments, to show the contributions of African Americans to U.S. society and culture. Jan Ernst Matzeliger was a big deal. We should know his name.

In 1880, a pair of shoes cost more than most families earned in a week because shoe-making was so labor and skill intensive. “Lasting”was the process of attaching the upper part of a shoe to its sole, and required such precision that only skilled and experienced cobblers could do it well enough to produce usable footwear. The best of them could only produce about 50 pairs of shoes in a typical workday, and that only by working long and tedious hours.

Jan Ernst Matzeliger, a Suriname-born immigrant, found his way to Lynn, Massachusetts, then considered the shoe capital of America. He went to work for pennies in a shoe factory and despite laboring in 10-hour shifts devoted himself after the quitting time whistle to try to solve the lasting problem of lasting. He had taught himself English; he had taught himself mechanical drawing, he had learned engineering skills despite being isolated and poor. Then for six years he tried to find a way to mechanize shoe lasting.

On March 20, 1883, the United States Patent Office issued Patent No. 274,207 to Jan Ernst Matzeliger for his lasting machine. It could produce up to 700 pairs of shoes in a day, and they were as good as the ones lasted by hand, and often better. Shoe prices were cut in half because production costs were cut by half. Working families could finally afford durable footwear. Children could wear comfortable, well-fitting shoes.

The rest of the story is a familiar and tragic one that has been shared by many inventors who do not have the business skills to match their innovation and mechanical talents. Matzeliger sold controlling interest in his invention to investors to get the machine produced, advertised, and sold. His lasting machine launched the United Shoe Machinery Corporation, which dominated the global industry as its investors made their fortunes. Matzeliger did not become rich; he continued to work on perfecting his machine until he died of tuberculosis at the age of 37, only six years after his revolutionary patent.

So deep was his obscurity that it wasn’t until more than a century after his death that he was finally inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame along with Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and my personal favorite (and similarly hopeless businessman), Walter Hunt, inventor of the safety pin as well as the first practical sewing machine.

Meanwhile, mass-produced shoes still get made using the principles Jan Ernst Matzeliger developed. One biography describes him as “The man who put the world on its feet.” That’s not too much of an exaggeration. He should be remembered.

_________________

Pointer: Howard Spendelow

Thank you. I will now think of Jan Ernst daily when I put on my shoes…

Always learn something new here.

I’ve noticed that history books tend to ignore inventions that affected day-to-day lives with only a few major exceptions. I think this is a mistake. Wars and political changes are important, but I’d argue that the invention of the spinning wheel had a bigger impact on peasants’ lives than which lord they paid taxes to.

Trot, trot to Boston,

Trot, trot to Lynne,

Watch for the holes,

That you don’t fall in.

Lynne, Lynne, the city of Sin.

“Over to the GE” where people from the surrounding towns worked building jet engines.

“Two Years Before the Mast” is a great book about sailing around the Horn to Southern California to buy a boatload of cow hides from the Spanish and return the hides to, wait for it, Lynne, Mass. to be turned into shoes.

I know it well. I was a messenger and mail room guy at the Sears Credit Central there. I’d drive into Boston to the Gothic Sears building in the Fens, pick up five boxes of green bar computer paper from various departments in the building that must have originally been what we’d now call a fulfillment center for Sears catalogue buys, and haul it back to Lynne and distribute it among the girls who were responsible for collecting the delinquent accounts via phone. Such primitive data management: moving data by box, hand truck and car. Sheesh.

Suriname. Still part of Holland. Why is it just the American South that’s still hounded for slavery? The Dutch had slave colonies throughout the Caribbean. Aruba, Bon Aire and Curacao (aka, “The ABCs”) and Suriname now produce black soccer players as well as major league ballplayers. We met any number of prosperous, integrated Surinamers in Amsterdam. Good for them.

(It’s “TLot tLot,” not “trot”)

I did not know that. I heard “trot” from Mrs. OB (as well as from my maiden aunt who’d do the routine with me on her lap) who was brought up in near to Lynne Saugus. What does “tLot” mean?

It’s the onomatopoeia Alfred Noyes made up to represent hoofbeats in “The Highway Man.” As in…

Tlot-tlot; tlot-tlot! Had they heard it? The horsehoofs ringing clear;

Tlot-tlot; tlot-tlot, in the distance? Were they deaf that they did not hear?