Several things led me to re-posting this Ethics Alarms entry from 2017.

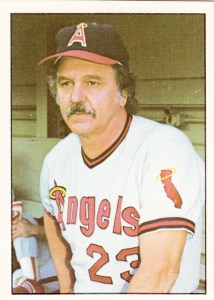

First of all, the MLB network showed a documentary on the career of George Brett today, and scene above, with Brett erupting in fury at the umpire’s call voiding his clutch, 9th inning home run, is one of the classic recorded moments in baseball history. There was also a recent baseball ethics event that had reminded me of Brett’s meltdown: Yankees manager Aaron Boone was thrown out of a game because a fan behind the Yankees dugout yelled an insult at the home plate umpire, and the umpire ejected Boone thinking the comments came from him.. When Boone vigorously protested that he hadn’t said anything and that it was the fan,Umpire Hunter Wendelstedt said, “I don’t care who said it. You’re gone!”

Wait, what? How can he not care if he’s punishing the wrong guy?

“What do you mean you don’t care?” Boone screamed rushing onto the field a la Brett. “I did not say a word. It was up above our dugout. Bullshit! Bullshit! I didn’t say anything. I did not say anything, Hunter. I did not say a fucking thing!” This erudite exchange was picked up by the field mics.

There was another baseball ethics development this week as well, one involving baseball lore and another controversial home run. On June 9, 1946, Ted Williams hit a ball that traveled a reported 502 feet, the longest he ever hit, and one of the longest anyone has hit. The seat was was painted red in 1984 (I’ve sat in it!), and many players have opined over the years that the story and the seat are hogwash, a lie. This report, assembling new data about the controversy, arrives at an amazing conclusion: the home run probably traveled farther than 502 feet.

But I digress. Here, lightly edited and updated, is the ethics analysis of the famous pine tar game and its aftermath:

***

I have come to believe that the lesson learned from the pine tar incident is increasingly the wrong one, and the consequences of this extend well beyond baseball.

On July 24, 1983, the Kansas City Royals were battling the New York Yankees at Yankee Stadium. With two outs and a runner on first in the top of the ninth inning, Royals third baseman George Brett hit a two-run home run off Yankee closer Goose Gossage to give his team a 5-4 lead. Yankee manager Billy Martin, however, had been waiting like a spider for this moment.

Long ago, he had noticed that perennial batting champ Brett used a bat that had pine tar (used to allow a batter to grip the bat better) on the handle beyond what the rules allowed. MLB Rule 1.10(c) states: “The bat handle, for not more than 18 inches from the end, may be covered or treated with any material or substance to improve the grip. Any such material or substance, which extends past the 18-inch limitation, shall cause the bat to be removed from the game.” At the time, such a hit was defined in the rules as an illegally batted ball, and the penalty for hitting “an illegally batted ball” was that the batter was to be declared out, under the explicit terms of the then-existing provisions of Rule 6.06.

That made Brett’s bat illegal, and any hit made using the bat an out. But Billy Martin, being diabolical as well as a ruthless competitor, didn’t want the bat to cause just any out. He had waited for a hit that would make the difference between victory or defeat for his team, and finally, at long last, this was it. Martin came out of the dugout carrying a rule book, and arguing that the home run shouldn’t count. After examining the rules and the bat, home-plate umpire Tim McLelland ruled that Brett used indeed used excessive pine tar and called him out, overturning the home run and ending the game.

Brett’s resulting charge from the dugout (above) is video for the ages. Continue reading