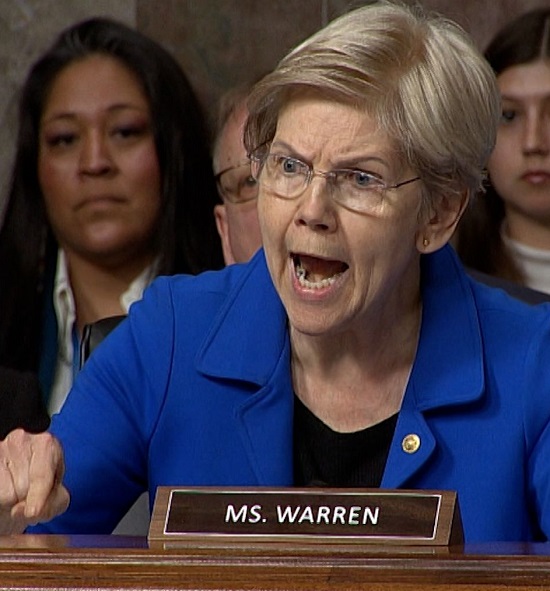

I have mentioned here frequently that one of two things I learned in college that have been most useful in my life and career is Leon Festinger’s Cognitive Dissonance Scale. The concept illustrated by the scale is also one of the most useful tools for ethical analysis, often essential to answering the question, “What’s going on here?” the entry point to many perplexing situations. Check the tag: it just took me 15 minutes to scroll though the posts that got it. I was surprised to find that I didn’t use the tag until 2014, when the scale helped me conclude that the Tea Party, then in ascendancy, was “doomed by a powerful phenomenon it obviously doesn’t understand: Cognitive Dissonance.” Heard much about the Tea Party lately? See, I’m smart! I’m not dumb like everybody says… I wrote then,

As psychologist Leon Festinger showed a half a century ago, we form our likes, dislikes, opinions and beliefs to a great extent based on our subconscious reactions to who and what they are connected with and associated to. This is, to a considerable extent, why leaders and celebrities are such powerful influences on society. It explains why we tend to adopt the values of our parents, and it largely explains many marketing and advertising techniques that manipulate our desires and preferences. Simply put, if someone we admire adopts a position or endorses a product, person or idea, he or she will naturally raise it in our estimation. If however, that position, product, person or idea is already extremely low in our esteem, even though his endorsement might raise it, even substantially, his own status will suffer, and fall. He will slide down the admiration scale, even if that which he endorses rises. If what the individual endorses is sufficiently deplored, it might even wipe out his positive standing entirely.

The implications of this phenomenon are many and varied, and sometimes complex. If a popular and admired politician espouses a policy, many will assume the policy is wise simply because he supports it. If an unpopular fool then argues passionately for the same policy, Festinger’s theory tells us, it might..

1. Raise the fool’s popularity, if the policy is sufficiently popular.

2. Lower support for the policy, if he is sufficiently reviled, and even

3. Lower the popularity of the admired politician, who will suffer for being associated with an idea that had been embraced by a despised dolt.

This subconscious shifting, said Festinger, goes on constantly, effecting everything from what movies we like to the clothes we wear to how we vote.

Here, for the heaven-knows-how-many-th time, is the scale in simplified form…

Continue reading →