by Curmie

Twentysomething years ago, a few months after completing my PhD, I got a phone call from my mentor in Asian theatre, who, upon learning job search wasn’t going as well as I might have hoped, asked if I wanted to teach a couple sections of the university’s Eastern Civilizations course. I asked if I was really qualified to teach such a course. His response: “You know something, and you can read.”

Based largely on his recommendation, I got an interview for the position. I made no attempt to conceal my ignorance of a lot of what I’d be teaching. But the department had struggled with grad students who had lost control of their classrooms, and I’d taught full-time for ten years before entering the doctoral program; I got the job. The head of the Eastern Civ program closed the interview with “There are some books in my office you’ll want to read before you start.” I knew something, and I could read.

That’s relevant to my consideration of the recent ruling of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Porter v. Board of Trustees of North Carolina State University, in which a tenured faculty member claimed to have been punished for arguing against certain initiatives undertaken by his department. I’m no lawyer, so there’s some legalese I’m not so sure about, and I have no interest in chasing down all the precedents cited by either the majority or the dissent to see if they really say what these judges say they say. But I know something and I can read.

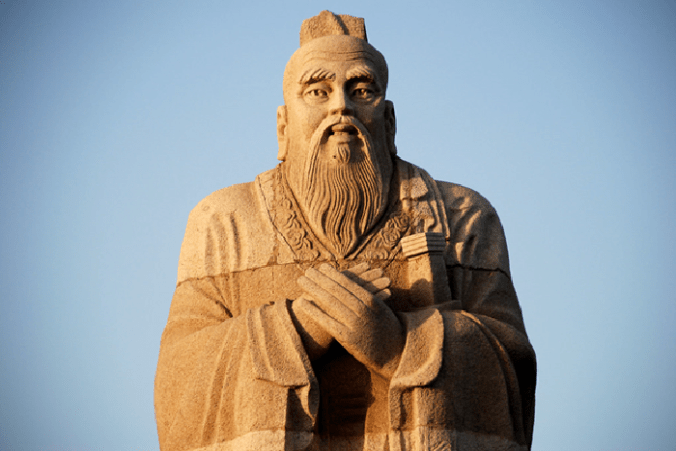

More to the point, one of the texts I taught in that Eastern Civ course was Confucius’s Analects, which I had to get to know a lot better than I did previously in order to teach it to someone else. One of the central tenets of Confucian thought was his argument against having too many laws, as no one could possibly predict all the various special circumstances surrounding every dispute. Context matters; timing matters; motives matter. Confucius’s solution was to turn everything over to a wise counselor (like him) who would weigh all the relevant elements on a case by case basis. That’s not the way our justice system works, nor would it be practical, but it’s easy to see its appeal… in theory, at least.

Significantly, Confucius’s reservations about laws’ inability to anticipate all the possible combinations of circumstances are the first cousin if not the sibling of what Jack calls the “ethics incompleteness principle” which asserts that there “are always anomalies on the periphery of every normative system, no matter how sound or well articulated.”