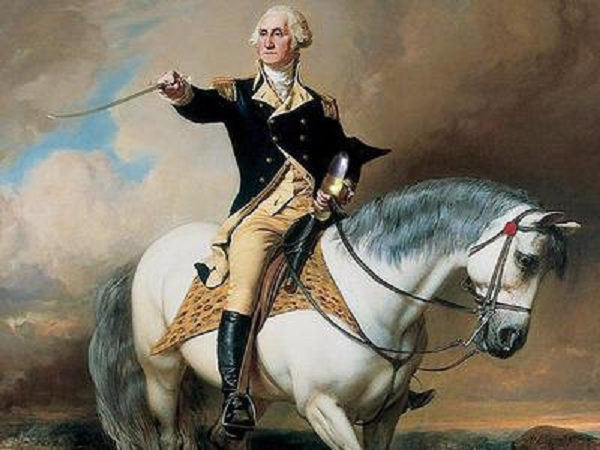

It’s George Washington’s birthday. Nine years ago I wrote, in one of my annual posts on perhaps our most important President (George Will calls him “the Indispensable Man) that something has gone seriously wrong when one’s blog has 287 posts on Donald Trump and only six about Washington. I don’t even want to think about what the count is now, but here is another one in George’s column.

George Washington’s father Augustine had at one time or another run across a list of 110 virtues that young men should adopt and practice in order to be become civil, respectful and honorable members of polite society. He made George, and presumably all his sons (he had six of them) copy them by hand to aid in memorizing the list. George, at least, dutifully committed to memory “110 Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation,” which was based on a document composed by French Jesuits in 1595; neither the author nor the English translator and adapter are known today. The elder Washington was following the theory of Aristotle, who held that principles and values began as being externally imposed by authority (morals) and eventually became internalized as character.

Those ethics alarms installed by his father stayed in working order throughout George’s remarkable life. It was said that Washington was known to quote the rules when appropriate, and never forgot them. They did not teach him to be the gifted leader he became, but they helped to make him a trustworthy one.

The list has been available on Ethics Alarms under Rule Book since its beginnings in 2009. By all means read the whole list; I have used it often in ethics seminars but haven’t referred to it here for too long. The 90 rules omitted in the list below contain some gems too, and many that raise curiosity about what exactly the author was thinking of. For example, I find #2. “When in company, put not your hands to any part of the body not usually discovered” and #3. “Show nothing to your friend that may affright him” intriguing.

Below are my 20 favorite entries from the list that helped make George George, therefore helped George make America America: