I am trying hard to write about something other than the Charley Kirk Ethics Train Wreck despite the din making even thinking about other ethics issues difficult. Naturally, my default solution is the Great American Ethics Genre: the American Western.

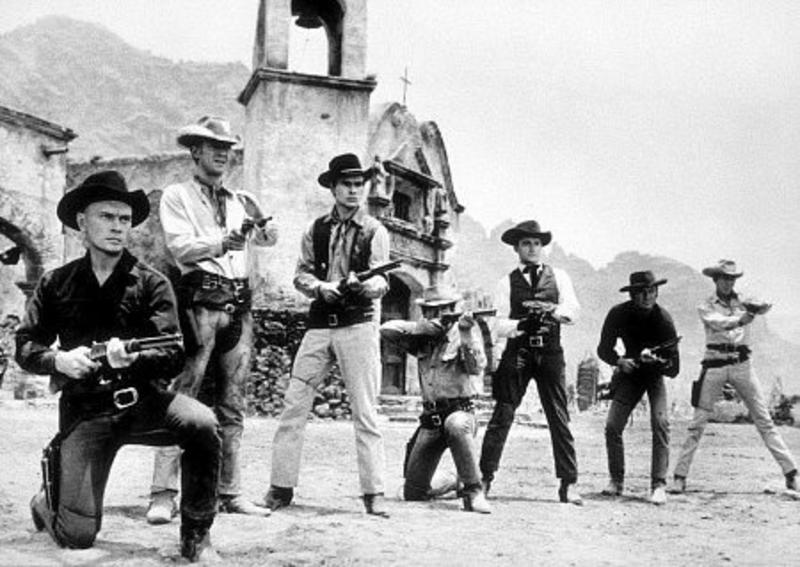

I have been bringing a younger friend up to speed in his cultural literacy pursuits, and recently had him view the original John Sturgis-directed version of “The Magnificent Seven,” a great ethics movie and one of the ten best Hollywood Westerns ever made, a tough field. I have written about the movie several times on EA, but I am abashed to say that it never quite sunk in what the film was really about until that last viewing.

The film is about professionalism. Once that bell rang, I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t realized it before. It is a filmed course in professionalism—the quality of justifying the trust a particular practitioner of an occupation dedicated to public service must maintain to be considered a professional. I would love to teach a professionalism course using the movie as the centerpiece.

Years ago, retired EA commenter Bob Stone-–I hope he isn’t Trump-Deranged now—wrote a piece for his own blog about how the film illustrated the difference between law and ethics. He wrote in part,

Law requires obedience to the enforceable, while ethics requires obedience to the “unenforceable.” …What is the “unenforceable” to which ethics demands obedience? For Chris Adams [the leader of “the Seven,” played by Yul Brenner), it’s his commitment. He had to keep his word, even though — or perhaps, in Chris’ case, because — no court would require him to. While Chris Adams was his own master, public servants serve two masters where ethics is concerned. They serve their city or state or county, which has its own code of ethics. The code is enforceable: Obey it or risk being fired, suspended or even prosecuted. But, at the same time they serve another, often more demanding, master: their inner selves with their own sets of unenforceables. The Golden Rule, unenforceable as it is, is much more demanding than any code of ethics, public or private, that I’ve ever seen. In fact, most of us expect more of ourselves and of the people we lead than mere compliance with regulations.

Bob came close, but missed a key element of professionalism, a term he didn’t mention. Those “unenforceables” determine whether a pursuit can call itself a profession in good faith. When the “unenforceables” aren’t observed or respected, a profession no longer serves the public interest or can be trusted to do so.

That is exactly what we have seen happen to the whole class of professionals since Trump Derangement and The Great Stupid washed over the land, as ideological bias, pursuit of wealth and power and ethics blindness have infected virtually all of the professions, and I say “virtually” despite being unable to think of a single one that hasn’t been corrupted. Maybe accountancy. Journalists, lawyers, doctors, the clergy, scholars, educators, elected officials, law enforcement officials, judges, scientists and yes, ethicists, have all forsaken the qualities that justify public trust to a tragic extent. “The Magnificent Seven” teaches why this is both wrong and destructive.

Bob Stone focuses upon the exchange that most clearly lays out the distinction between what a professional has to do and what he or she should do. When Vin (Steve McQueen) suggests that the situation (trying to defend a small Mexican town of farmers and their families from a Mexican gang of thieves who steal their crops) has become hopeless and the prudent decision would be to give up, Chris says, “You forget one thing — we took a contract.” Vin replies, “It’s not the kind any court would enforce.” “That’s just the kind you’ve got to keep,” Chris replies.

That exchange, however, is just the tip of the professionalism iceberg. Every member of the Seven represents a different variety of professional at a different stage of the realization of what that status means, though all regard themselves as professional gunfighters. Chris takes assignments that he believes are on the right side: he is like a mission lawyer such as Clarence Darrow. Vin has been a pure mercenary, but is in the process of appreciating the value of principle. Harry, Chris’s old freind, is a professional only in the sense that he makes his living as a hired gun. He doesn’t believe that Chris would take a job that pays so little. (When the representative of the farmers tells Yul/Chris that all they can pay Chris and his recruits are the paltry valuables collected from the town and that it is everything they have, Chris says, “I have been offered a lot for my work, but never everything.”) Bernardo, played by Charles Bronson, accepts the job because he is desperate for cash, but treats the commitment no differently than if it were a lucrative deal. Britt, James Coburn’s character, is described as not caring about money, just his own standards of excellence: his “clients” benefit as he pursues the elusive ideal. Robert Vaughn’s broken gunfighter Lee is a burned-out professional, ashamed of his decline in skill and purpose, trying to regain self-respect. Finally, Chico, played by Horst Buchholtz, is the novice, in the process of learning what a professional is.

When Chris’s team appears to be defeated, as the Mexican gang turns the farmers against them and forces them to leave at gunpoint, the gang’s leader Caldera (Eli Wallach, who steals the movie as well as the farmers’ crops) lets them keep their own guns as “professional courtesy.” Vin tells Chris that the mistake he made was “caring.” It’s a valid point: professionals must maintain distance from their clients, patients and those who rely on them while still maintaining loyalty and dedication to their stakeholders’ interests. Caring is emotion, and emotion causes bad decisions. Yet a professional who doesn’t care at all about those he or she assists is inhuman, and you shouldn’t–can’t— trust inhumans. The film lays out the core challenge of professionalism in that scene. Finding the right balance is an ancient conundrum.

When the Seven have been ushered out of the town and prepare to leave, it is Coburn, the idealist, who first breaks ranks. The rest know him to be the epitome of a professional; he is a role model. When Britt announces he is returning to the town to finish the job he committed to, Vin, now a believer in professionalism, is the first to join him. Chris, the leader, sits back and waits for his team to come to the right decision on their own: he only shows that he’s returning to the town too after all have announced that the mission is still on except Harry and Lee.

Harry, the mercenary, pronounces the rest crazy—he doesn’t understand any motives but monetary ones, and exhorts Lee to leave with him, saying that he has no obligation to go back to the town. “Except to myself,” Lee replies. For his self-image and self-respect are based on his identity as a professional, and if he dies showing that he was worthy of trust, so be it. (He does.)

Bob Stone calls Harry a coward, but that is unfair, for Harry does return to the town after all, demonstrating his loyalty to his friends and comrades who trusted him. At the end, principle trumps avarice: Harry too has learned the essence of professionalism. (He gets killed in the process, unfortunately)

After the dust has cleared, only Chris, Vin and Chico are left alive, but the town is finally free. With his dying breath, Calvera expresses wonderment at Chris’s determination to help the farmers. “A town like this? A man like you? Why?” he gasps. The professional bandit still thinks “professional” only means that one does the job for money. He doesn’t get it.

Too bad he hadn’t seen “The Magnificent Seven.”

As Yul and Steve McQueen prepare to gallop into the sunset, Chris observes that gunfighters like them—professionals—never win. The farmers—those who trusted the Seven—were the winners. That’s right, because true professionals’ only goal is for the client/patient/public to gain, not themselves. They just need to survive to fight another day…for the public good.

Wow! One is left to wonder if the script writers fully understood the ethical questions each character was going to present – and ultimately provide answer – to the viewers. If they did, that is some very complex thinking and writing!

I’ve watched a bunch of westerns in my life, but never “The Magnificent Seven.” I think you have convinced me to change that.

And it also begs the question: have you ever shared your list of Top-10 Westerns? I would love to see it!

1. Whatever you do, make sure it’s the original and not the DEI remake, which jettisoned ethics entirely in the screenplay.

2. The screenwriters had the model of “The Seven Samurai,” which led them down this path. Samuraiwere all about honor and professionalism. Today it is hard to equate them with gunfighters, but the Western canon is full of gunfighters who are only interested in helping the public, fighting for truth, justice and the American way, and against the bad guys, sometimes cattle barons, sometimes corrupt officials, sometimes bad gunfighters, sometimes evildoers in general.

3. My top 13 Western movies, in no particular order, are..

Shane

The Magnificent Seven

High Noon

The Searchers

Red River

Rio Bravo

Stage Coach

Silverado

Destry Rides Again (which “Blazing Saddles” satirized)

Winchester 73

Hondo

The Oxbow Incident

The Ballad of Cable Hogue

But “Lonesome Dove,” a TV mini-series, is the best of all.

Note: I do not regard any of the Spaghetti Westerns as true Westerns: they were Mafia stories in Western garb and ethically inert.

I remember being taken to a Clint Eastwood movie, probably as a twelve- or thirteen-year-old, by a friend who was a bit of a wild man at that age. I had no idea what to make of the movie and have never seen another one. The movie seemed to be a thing I was supposed to think was really cool but simply did not get. The movie also struck me as looking, and sounding, cheap.

That’s a great list…I LOVED “The Searchers” but might have “The Sons of Katie Elder” somewhere in there as well.

ARRRRGHHH! I left out “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”…easily in the top 20, maybe in the top 10.

“[P]rofessionals must maintain distance from their clients, patients and those who rely on them while still maintaining loyalty and dedication to their stakeholders’ interests. Caring is emotion, and emotion causes bad decisions. Yet a professional who doesn’t care at all about those he or she assists is inhuman, and you shouldn’t–can’t— trust inhumans.”

Amen. Having been raised by my mother to be a Catholic priest, being a first-generation lawyer was a blunder. I was in uncharted waters. Up you-know-where without a paddle. Which I only realized too late and essentially after the fact. It’s an odd profession and largely counter-intuitive.

I can’t believe what’s happened to law schools and the bar associations since I was in law school in the late ’70s. It’s a worse catastrophe than what’s descended upon the American academy since I graduated from college in the early ’70s.

I would add “the 3:10 to Yuma” from 1957

Definitely in the top 20. Quirky one for Glenn Ford: far better than the remake.

I would add “Unforgiven” to the top of that list.

I am not a fan of “Unforgiven,” or any of the anti-Western Westerns. “Unforgiven” is a vengeance movie like “Death Wish.” Star Wars is more of a Western than “Unforgiven.” Other anti-Western Westerns: “The Wild Bunch” and “McCabe and Mrs. Miller.” Also another Gene Hackman villain turn, the satirical “The Quick and the Dead.”