I have a lifetime love affair with the Presidents of the United States.

I love these guys, every one of them. The best of them are among the most skilled and courageous leaders in world history; the least of them took more risks and sacrificed more for their country than any of us ever can or will, including me. Every one of our Presidents, whatever their blunders, flaws and bad choices, was a remarkable and an accomplished human being, and exemplified the people he led in important ways. Every one of them accepted not only the burden of leadership, but the almost unbearable burden of leading the most dynamic, ambitious, confusing, cantankerous and often unappreciative nation that has ever existed. I respect that and honor it.

I have been a President junkie since I was eight years old. It’s Robert Ripley’s fault. My father bought an old, dog-eared paperback in the “Believe it or Not!” series and gave it to me. It was published in 1948. One of Ripley’s entries was about the “Presidents Curse”: every U.S. President elected in a year ending with a zero since 1840 (William Henry Harrison) had died in office, and only one President who had dies in office, Zachary Taylor, hadn’t been elected in such a year. The cartoon featured a creep chart—I still have it—listing the names of the dead Presidents, the years they were elected, and the year 1960 with ???? next to it. When Jack Kennedy, the youngest President ever elected, won the office in 1960, my Dad, who by that time was sick of me reminding him of the uncanny pattern, said, “Well, son, so much for Ripley’s curse!”

You know what happened. (John Hinckley almost kept the curse going, but Ronald Reagan, elected in 1980, finally broke it.) That year I became obsessed with Presidential history, devising a lecture that gave an overview of the men and their significance in order. My teacher allowed me to inflict it on my classmates. Much later, Presidential leadership and character was the topic of my honors thesis in college. When I finally got a chance to go to Disneyland, the first place I went was the Hall of Presidents. When the recorded announcer said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, the Presidents of the United States!” and the red curtain parted to show the audio-animatrons of all of them together, it was one of the biggest thrills of my life.

Today I will honor our past Presidents with some of my favorite facts about each of them, trying hard not to get carried away. Is it ethics? It’s leadership, which has always been the dominant sub-topic here, but yes, it’s ethics. I know I’m hard on our Presidents, as I think we all should be: supportive, loyal, but demanding and critical. I am also, however, cognizant of how much they give to the country and their shared determination to do what they think, rightly or wrongly, is in the country’s best long-term interests. File this post under respect, fairness, gratitude, and especially citizenship. And now…

“Ladies and Gentlemen, the Presidents of the United States!“

George Washington

I live within 15 minutes of Mount Vernon, so this is George Central. The most intriguing George Washington story to me is his miraculous survival at the Battle of the Monongahela, a fierce skirmish with the Indians during the French and Indian War, when he was a young British officer. There were eighty-six British and American officers involved in the battle; sixty-three of them died. The Native American warriors fighting them later acknowledged that they were targeting all officers, and particularly Washington, who then as later and always had immense presence, especially since he was uncommonly tall for the era. Yet Colonel Washington was the only officer on horseback who was not killed. The Indians reported that they aimed and shot at him repeatedly with no apparent effect, and believed he was protected by a supernatural power and that no bullet, bayonet, arrow or tomahawk could harm him.

Washington later wrote to his brother John:

“By the all-powerful dispensations of Providence, I have been protected beyond all human probability or expectation; for I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot under me, yet escaped unhurt, although death was leveling my companions on every side of me!”

I’ve seen the coat. Those sure look like bullet holes…right in the chest. Did this fluke explain Washington’s much remarked-upon practice of leading his ragtag Revolutionary War soldiers into battle in fill regalia, on his white stallion, despite the fact that he presented an irresistible target, and one lucky shot could have ended the American dream of independence? Several Presidents had what they considered to be remarkable escapes from death, and the experience led them to regard themselves as either chosen by Fate for great deeds, or simply different from normal men—a common state of mind for leaders.

John Adams

The best of John Adams can be seen in his letters to his wife, mentor and soul mate Abigail. (She would have made a better President than her husband. Unfortunately, she couldn’t even vote.) He was the first occupant of the (unfinished) White House, and in November of 1800, was sitting in the space that is now the State Dining Room when he wrote her, “May none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof.” In 1944 President Franklin D. Roosevelt, directed that those be carved into the fireplace mantle of the room, and there they remain.

Thomas Jefferson

My favorite fact about Jefferson is what a slob he was, often appearing in public looking disheveled and wearing soiled or mismatched clothes. He really was like a stereotype of the mad philosopher, with his mind so occupied with higher thoughts that the mundane matters of going through the day escaped his attention. Jefferson’s presidency was also distinguished by his development of a collaborative approach to Congress, unlike Washington and Adams. Jefferson was a gourmand, and loved to entertain, so he combined business with pleasure, regularly inviting members of Congress, who were mostly forced to live in gloomy boarding houses, to the White House for dinner, where he debated, cajoled, charmed and persuaded them. It worked, too.

And it would work today. That’s all I’m going to say about it.

James Madison

Madison’s term was marred by a foolish war against Britain that could have ended the country, had it not been for live oak, some luck, and a failure of British will. His perky wife Dolley, 16 years his junior, was more popular than he was. I am fascinated that we had a President who weighted less than 100 pounds soaking wet, especially since the office has been dominated by big and physically attractive men. (See here.)

James Monroe

Monroe was probably our least appreciated great President. He was also the first truly poor President, though Jefferson’s high standard of living put him in debt as well. Monroe was never wealthy at any time in his life, and died in poverty,

John Quincy Adams

John Adams’ clone of a son was the main player in one of the best Presidential stories of all. Partial to skinny-dipping in the Potomac, John Quincy Adams was once surprised mid swim by a female newspaper reporter, who sat on his clothes while forcing him to consent to a naked interview. It would make a great play.

Andrew Jackson

The attempted assassination of Old Hickory (the first such attempt on any President) might be my favorite Presidential story, though. On January 30, 1835, President Jackson came to the U.S. Capitol to attend the funeral of a member of Congress. As he left the building, a rejected office seeker named Richard Lawrence stepped out from behind a pillar and fired a flintlock pistol point blank at Andy’s chest. The gun misfired, and Lawrence had flunked the famous requirement that if you strike at the king, you better kill him. Instead, he was face to face with one of the most ill-tempered, tough, dangerous men in America. And that man was furious.

Eyewitnesses saw the now terrified Lawrence pull out another pistol and fire again, and this pistol also misfired. Jackson then (it is unrecorded whether Lawrence had time to scream, “Oh NOOOOO!!!”) began methodically attempting to beat Lawrence to death with his silver-topped cane. He would have killed him, except that several men restrained the President. Reportedly one of them was Rep. David Crockett (D-Tenn.). Why this incident has never been filmed, I don’t know.

Lawrence’s guns were tested after Jackson’s brush with death, and they worked perfectly. It was later estimated that the odds of both guns misfiring during the assassination attempt were 1 in 125,000.

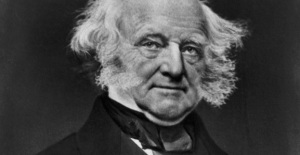

Martin Van Buren

No, he wasn’t Aaron Burr’s illegitimate son. Still, he was unique: He was the first president born in the U.S., and the first born after the Declaration of Independence in 1776. More significantly, he was the first President with no English background and the only President to this day who did not have English-speaking native parents. Van Buren spoke Dutch growing up, and English was his second language.

He was also the first of the ill-starred “designated successors.” Jackson was so popular and had so much power in his party that he essentially picked the next President, his friend and protegé Van Buren. Van Buren was no Andy, and later Taft would prove to be no Teddy, and George H.W. Bush would be no Ronnie. They all were one-term Presidents. You can’t inherit leadership skills.

William Henry Harrison

The demise of our briefest tenured President is a lesson in hubris. Harrison was 68, the equivalent today of being over 90, and much had been made of his advanced age during the campaign, despite the fact that he won in the greatest popular vote landslide ever. To prove that he was still hardy and vital, Harrison insisted on delivering his inaugural address on a cold, wet day without wearing a top coat. Just to make sure the point was made, Harrison spoke for an hour and fifteen minutes, a record that still stands. Naturally, he caught a cold, and it killed him a month later.

But you and Robert Ripley know what really killed him, right?

John Tyler

The Constitution is ambiguous about what happens when a President dies: the language could be interpreted to mean that a special election is held to elect a successor, with the Vice President serving in the interim. Nope, said John Tyler, Harrison’s veep: it means that the Vice President serves out the entire term. This was a wise and fortuitous, if self-serving, call. We have Tyler to thank for Teddy Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and LBJ.

Incredibly, John Tyler’s grandsons are still alive ( Tyler was born in 1790), and one of them, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, born in 1928, still lives at John Tyler’s plantation in Virginia. I saw him one, from a distance.

Six Degrees of William Henry Harrison!

The Presidents between #7, Jackson, and #16, Lincoln, are almost entirely unknown to most of the public: not one in a hundred can name them all, and of those almost none can name them in order. Eight one-term Presidents, all trying to stave off the civil war in various ways, and all failing that mission.

I will never understand why learning the Presidents in order isn’t a standard requirement in the public schools. It’s not hard; it is a useful tool in placing events in American history, and it prevents embarrassments like the Cornell law grad I once worked with who couldn’t place the Civil War in the right century. Besides, we’re Americans, damn it. The least we owe the 43 patriots who have tried to do this job, some at the cost of their lives, many their health, and many more their popularity, is their place in our history and their names.

On with hailing the Chiefs with some of my favorite facts about them:

James K. Polk

“Hail to the Chief,” which had been sporadically in use since Madison’s day, became the official anthem of the office during the Polk Administration. Polk was a small, unimpressive man, and it was said that he needed the musical announcement when he entered a room or no one would notice him. Looks can be deceiving. James K. Polk was as wily, tough and as ruthless as they come. One reason may be that he was another Presidential survivor of an ordeal that would kill most people: as a teenager, he underwent a bloody frontier operation for gallstones with no anesthesia, tied to a table, biting on a rag.

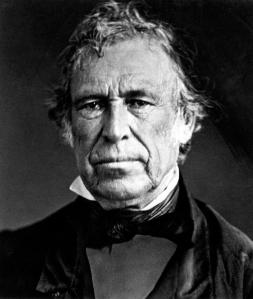

Zachary Taylor

General Taylor, who was pursued by both the Whigs and the Democrats who both wanted to nominate him for President, was a great experiment He was not a member of any political party, had never held public office prior to becoming President, and had never even voted before becoming Chief Executive. He was also nearly illiterate. We often long for an apolitical President, a true, rather than a pretend, “outsider.” Taylor would have been an interesting test case, though the pre-Civil War political and social chaos was hardly the most promising period to try out the theory. Unfortunately he died of cholera less than half-way into his administration.

And he wasn’t even elected in a year ending in a zero!

Millard Fillmore

The President with my favorite President’s name had an undistinguished tenure, but he was instrumental in establishing the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in this country after he left office. I will always think well of him for that.

Franklin Pierce

New Hampshire’s only President had the most tragic life of those who escaped the White House still breathing. Bad things were always happening to him; for example, he was wounded painfully in the Mexican-American War when he was thown by his horse against the horn of his saddle, harming his testicles. His wife, Jane, was chronically ill and had emotional problems that were exacerbated by the deaths of the Pierces’ two youngest sons. She hated politics, hated everything Pierce did and the people he associated with, and didn’t seem too crazy about Franklin either, nagging and berating him constantly and mercilessly. Then, on the way to Washington, D.C. after her worthless husband had blundered his way into being elected President of the United States, Jane watched their surviving 11-year-old son get beheaded when the train carrying the Pierces ran off the rails. Franklin saw the horror too. (The boy was the only casualty.)

The couple arrived grief-stricken and broken. Jane refused to participate in affairs of state, blamed Pierce for their son’s death, and continued to berate him. The President, quite possible suffering from PTSD himself, began drinking heavily. Meanwhile, the country was falling apart, with the divisions and violence over slavery escalating and requiring firm, measured, deft leadership, which Pierce was not equipped to provide. He knew it, too. He was almost certainly an alcoholic, but if he hadn’t been, he would have been driven to drink anyway. Upon leaving office in 1857, Pierce is believed to have said in answer to someone asking what he was going to do now, “There’s nothing left to do but get drunk.” Jane kept nagging and abusing him until she died in 1863, and in 1869, his liver ruined, Pierce died himself.

One of his best friends as a young man was Nathanial Hawthorne. Franklin Pierce’s tragic life played out like one of his pal’s stories.

James Buchanan

When he is not being labelled our worst President (though one could not be worse than Pierce) James Buchanan is often distinguished as the only bachelor President. In fact, he was probably our first gay President. His engagement to his fiancee, Ann Coleman, broke off under mysterious circumstances, and she died not long after. Was he unmarried out of grief or guilt? Historians tend to think not. Buchanan’s long-time companion, Senator William Rufus King (D-Al), was referred to as his “better half,” ‘’his wife,” and “Aunt Fancy,” and in the Capital, the pair were called the “Siamese twins,” a euphemism for gays and lesbians. When King was appointed envoy to France in 1844, Buchanan complained to friends about his loneliness, saying “I have gone wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any of them.”

Abraham Lincoln

The giant among Presidents, literally and figuratively, is so iconic that we tend to take his brilliance and complexity for granted. Lincoln was another President who nearly died before he could lead the nation: when he was 10, he was kicked in the temple by a horse and was unconscious from the blow until the following day. His neighbors thought he was dead, or as good as dead. Some historian and doctors have speculated that Lincoln suffered permanent brain damage from the incident, explaining his life-long fits of depression and the relative lack on animation of the left side his face (he was virtually blind in his left eye as well.)

If Lincoln was brain damaged, find me a horse. Many of his speeches are imprinted on our souls, so I’ll take this opportunity to highlight one of Abe’s earlier efforts,an address he gave at the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois on January 27, 1837. His main topic was “The perpetuation of our political institutions,” but the speech was inspired by the murder of Elijah Lovejoy, an abolitionist and activist who began publishing a paper in Alton, Illinois. On November 7, 1837, a pro-slavery mob set the building where he kept his printing press on fire and shot Lovejoy dead. Lincoln’s message was a condemnation of mob violence. Here is the most memorable passage, and it’s still relevant today:

…I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country—the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions in lieu of the sober judgment of courts, and the worse than savage mobs for the executive ministers of justice. This disposition is awfully fearful in any and that it now exists in ours, though grating to our feelings to admit, it would be a violation of truth and an insult to our intelligence to deny. Accounts of outrages committed by mobs form the every-day news of the times. They have pervaded the country from New England to Louisiana, they are neither peculiar to the eternal snows of the former nor the burning suns of the latter; they are not the creature of climate, neither are they confined to the slaveholding or the non-slaveholding States. Alike they spring up among the pleasure-hunting masters of Southern slaves, and the order-loving citizens of the land of steady habits. Whatever then their cause may be, it is common to the whole country.

It would be tedious as well as useless to recount the horrors of all of them. Those happening in the State of Mississippi and at St. Louis are perhaps the most dangerous in example and revolting to humanity. In the Mississippi case they first commenced by hanging the regular gamblers—a set of men certainly not following for a livelihood a very useful or very honest occupation, but one which, so far from being forbidden by the laws, was actually licensed by an act of the legislature passed but a single year before.

Next, negroes suspected of conspiring to raise an insurrection were caught up and hanged in all parts of the State; then, white men supposed to be leagued with the negroes; and finally, strangers from neighboring States, going thither on business, were in many instances subjected to the same fate. Thus went on this process of hanging, from gamblers to negroes, from negroes to white citizens, and from these to strangers, till dead men were seen literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every roadside, and in numbers that were almost sufficient to rival the native Spanish moss of the country as a drapery of the forest.

Turn then to that horror-striking scene at St. Louis. A single victim only was sacrificed there. This story is very short, and is perhaps the most highly tragic of anything of its length that has ever been witnessed in real life. A mulatto man by the name of McIntosh was seized in the street, dragged to the suburbs of the city, chained to a tree, and actually burned to death; and all within a single hour from the time he had been a freeman attending to his own business and at peace with the world.

Such are the effects of mob law, and such are the scenes becoming more and more frequent in this land so lately famed for love of law and order, and the stories of which have even now grown too familiar to attract anything more than an idle remark.

But you are perhaps ready to ask, “What has this to do with the perpetuation of our political institutions?” I answer, “It has much to do with it.” Its direct consequences are, comparatively speaking, but a small evil, and much of its danger consists in the proneness of our minds to regard its direct as its only consequences. Abstractly considered, the hanging of the gamblers at Vicksburg was of but little consequence. They constitute a portion of population that is worse than useless in any community; and their death, if no pernicious example be set by it, is never matter of reasonable regret with any one. If they were annually swept from the stage of existence by the plague or smallpox, honest men would perhaps be much profited by the operation. Similar too is the correct reasoning in regard to the burning of the negro at St. Louis. He had forfeited his life by the perpetration of an outrageous murder upon one of the most worthy and respectable citizens of the city, and had he not died as he did, he must have died by the sentence of the law in a very short time afterward. As to him alone, it was as well the way it was as it could otherwise have been.

But the example in either case was fearful. When men take it in their heads to-day to hang gamblers or burn murderers, they should recollect that in the confusion usually attending such transactions they will be as likely to hang or burn some one who is neither a gambler nor a murderer as one who is, and that, acting upon the example they set, the mob of to-morrow may, and probably will, hang or burn some of them by the very same mistake. And not only so; the innocent, those who have ever set their faces against violations of law in every shape, alike with the guilty fall victims to the ravages of mob law; and thus it goes on, step by step, till all the walls erected for the defense of the persons and property of individuals are trodden down and disregarded. But all this, even, is not the full extent of the evil. By such examples, by instances of the perpetrators of such acts going unpunished, the lawless in spirit are encouraged to become lawless in practice; and having been used to no restraint but dread of punishment, they thus become absolutely unrestrained. Having ever regarded government as their deadliest bane, they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations, and pray for nothing so much as its total annihilation.

While, on the other hand, good men, men who love tranquillity, who desire to abide by the laws and enjoy their benefits, who would gladly spill their blood in the defense of their country, seeing their property destroyed, their families insulted, and their lives endangered, their persons injured, and seeing nothing in prospect that forebodes a change for the better, become tired of and disgusted with a government that offers them no protection, and are not much averse to a change in which they imagine they have nothing to lose. Thus, then, by the operation of this mobocratic spirit which all must admit is now abroad in the land, the strongest bulwark of any government, and particularly of those constituted like ours, may effectually be broken down and destroyed—I mean the attachment of the people.

Whenever this effect shall be produced among us; whenever the vicious portion of [our] population shall be permitted to gather in bands of hundreds and thousands, and burn churches, ravage and rob provision stores, throw printing-presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure and with impunity, depend upon it, this government cannot last. By such things the feelings of the best citizens will become more or less alienated from it, and thus it will be left without friends, or with too few, and those few too weak to make their friendship effectual. At such a time, and under such circumstances, men of sufficient talent and ambition will not be wanting to seize the opportunity, strike the blow, and overturn that fair fabric which for the last half century has been the fondest hope of the lovers of freedom throughout the world.

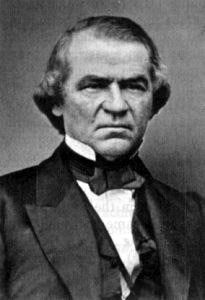

Andrew Johnson

Johnson was a terrible President, thrust by John Wilkes Booth in office at the worse possible time, for him and the nation that needed an unusually steady hand at the helm. He was a poor negotiator, stubborn, quite possibly another alcoholic, and had to follow Abraham Lincoln, which would have made him look weak by comparison even if he had been much better.

Still, he is the greatest Horacio Alger story of all the Presidents. He was dirt poor and indentured when a boy to a tailor as a virtual slave. Johnson escaped, there was bounty offered for anyone that caught and returned him. One would think that Johnson’s own experience would naturally engender in the 17th President some empathy for former black slaves when he was in a position to help them, but it did not. In fact, he later owned slaves, and, like Thomas Jefferson, may have fathered children with one of them.

Johnson was taught to read and write with professional competence by his wife. In his case especially, but with all of these men, rising to be even a lousy President is a remarkable achievement. Falling victim to the Peter Principle is a constant risk when you reach the very top, and in no field is that more of a peril than national leadership.

Ulysses S. Grant

My son is named after Grant, arguably the nicest and most sensitive of our Presidents. (How this sensitive man was able to sacrifice his soldiers in the thousands to win the horrible battles he did is an enigma.) As a cadet at West Point he drew pictures of horses obsessively; in the field, he refused to allow any of his men to see him unclothed. He loved his wife passionately, and wouldn’t allow her to get her badly crossed eyes fixed, because “God made her that way.” When his daughter was married, he retired to his bedroom and could be heard sobbing for over an hour.

As President, he was fatally handicapped by his nature, which caused him to trust people he shouldn’t and allowed others to exploit his good nature. The result was several scandals engineered by his appointees and associates, including Crédit Mobilier and the Whiskey Ring. Yet he had a natural aptitude for leadership, as his superb autobiography proved on every page. He could manage and lead; what he was bad at was manipulation, deceit, pretense, and retribution—in short, politics.

In one odd area, his customary sensitivity was completely lacking. He hated music of any kind.

Rutherford B. Hayes

Hayes appears to have had something of a female fixation. He was raised by his older sister and his mother, and of his two wives, one had the same name as his sister and looked like his mother , while his other wife looked like his sister and had the same name as his mother. He was far from a wimp, however: of the Presidents who saw action in the civil war, he was the only one wounded, and he was wounded four times.

Hayes would have been a terrific President in almost any other era. As it was, he was handicapped by the corrupt deal Republicans cut with Democrats to give Hayes the 1876 election despite finishing second in popular votes—the GOP got Hayes, and the South got rid of Federal troops and were able top go back to discriminating against African Americans—and the fact that the election was widely regarded as “stolen.” In this case, it really was.

James A. Garfield

Garfield is another of the great “what ifs?” on Presidential history. He was brilliant, he was brave, he was principled, and he was charismatic. Unfortunately, he had the Three Stooges on his medical team, so a non-mortal wound from the gun of genuine whack job Charles Guiteau (He wrote a poem that he delivered on the scaffold before they hung him; Stephen Sondheim set it to music for the highlight of his strange, dark musical, assassins. That’s a great trivia question: Which Presidential assassin wrote the lyrics to Broadway song?) killed Garfield anyway because his doctors poked, dug, cut and prodded so much trying to remove the bullet that infection did him in.

Garfield also had a super-power. At parties, he would simultaneously translate an English passage into Latin and classic Greek, writing one language with his right hand as he wrote the other with his left.

Chester A. Arthur

Chester is one of my favorites. He was added to the Garfield ticket as a sop to the corrupt Republican machine in New York, of which Arthur was a card-carrying member. Indeed, his mentor was the infamous political boss, Roscoe Conkling, who assumed he could count on a compliant Arthur to oppose the political reforms favored by Garfield that threatened Conkling’s power and livelihood.

Arthur, however, was apparently listening when President Hayes said, in his most famous quote, “He serves his party best who serves his country best.” Once in office as President, Arthur championed and signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, and strongly enforced it. He then blocked politics as usual by vetoing Republican pork barrel projects. He was regarded as a traitor by his party: he was never seriously considered for re-nomination in 1884. Arthur was one of the better Presidents under difficult circumstances, and an Ethics Hero.

The Presidents really get interesting now, as a political leadership culture in the U.S. matures, the stakes of failure become greater, and technology, labor upheaval, expanding big business and greater influence on world affairs transforms the Presidency into truly the toughest job on earth.

Grover Cleveland

Another one of my favorites, Cleveland was known for telling the truth ( he as called “Grover the Good”), but he participated in one of the most elaborate deceptions in Presidential history.

As explained in historian Matthew Algeo’s 2011 book, “The President Is a Sick Man,” President Cleveland noticed an odd bump on the roof of his mouth in the summer of 1893, shortly after he took office for the second time. (Cleveland is the only President with split terms, the hapless Republican Benjamin Harrison winning an electoral college victory that gave him four years as the bland filling in a Cleveland sandwich.) The bump was diagnosed as a life-threatening malignant tumor, and the remedy was removal. Cleveland believed that news of his diagnosis would send Wall Street and the country into a panic at a time when the economy was sliding into a depression anyway, and agreed to an ambitious and dangerous plan to have the surgery done in secret. The plan was for the President to announce he was taking a friend’s yacht on a four-day fishing trip from New York to his summer home in Cape Cod. Unknown to the press and the public was that the yacht had been transformed into a floating operating room, and a team of six surgeons were assembled and waiting.

The 90 minute procedure employed ether as the anesthesia, and the doctors removed the tumor, five teeth and a large part of the President’s upper left jawbone, all at sea. They also managed to extract the tumor through the President’s mouth while leaving no visible scar and without altering Cleveland’s walrus mustache. Talking on NPR in 2011, historian said,

“I talked to a couple of oral surgeons researching the book, and they still marvel at this operation: that they were able to do this on a moving boat; that they did it very quickly. A similar operation today would take several hours; they did it in 90 minutes.”

But the operation was a success. An artificial partial upper jaw made of rubber was installed to replace the missing bone, and Cleveland, who had the constitution of a moose, reappeared after four days looking hardy and most incredible of all, able to speak as clearly as ever. How did he heal so fast? Why wasn’t his speech effected? He endures doctors cutting out a large chuck of his mouth using 19th century surgical techniques and is back on the job in less than a week? No wonder nobody suspected the truth.

Then, two months later, Philadelphia Press reporter E.J. Edwards published a story about the surgery, thanks to one of the doctors anonymously breaching doctor-patient confidentiality. Cleveland, who in his first campaign for the White House had dealt with Republican accusations that he had fathered an illegitimate child by publicly admitting it, flatly denied Edwards’ story, and his aides launched a campaign to discredit the reporter. Grover the Good never lies, thought the public, so Edwards ended up where Brian Williams is now. His career and credibility were ruined.

Nobody outside of the participants knew about the operation and the President’s fake jaw until twenty-four years later, after all the other principals were dead except three witnesses. One of the surgeons decided to publish an article to prove that E.J. Edwards had been telling the truth after all.

This is a great ethics problem. Was it ethical for Cleveland to keep his health issues from the public? In this case, yes, I’d say so. Was it unethical for the doctor to break his ethical duty? Of course. Was Edwards ethical to report the story? Sure.

The tough question is: Was Cleveland ethical to deny the story and undermine the reporter’s credibility? I think it was a valid utilitarian move, and barely ethical: it was better for the nation to distrust one reporter than the President, especially when his secret was one he responsibly withheld, and his doctor unethically revealed.

Benjamin Harrison

The grandson of William Henry Harrison was afraid that he’d be electrocuted by the newly installed electric lights in the White House, so instead of turning them off himself, he had the servants do it. Ethically, this is like having your official taster risk getting poisoned in your place.

That’s all I need to know about Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President.

William McKinley

There’s a statue on the Antietam Battlefield in Maryland, scene of the bloodiest single day of the Civil War. It is the only Civil War statue dedicated to a commissary sergeant, and the soldier honored is William McKinley, who risking his life repeatedly as he brought hot coffee and food to the Union Army throughout the battle, while so many bullets were being fired that the air itself was described as “gray.”

McKinley was an effective and well-loved leader. He was also one of the nicer guys to inhabit the White House. His wife, Ida, had been emotionally and mentally damaged by a series of personal tragedies, and was also epileptic. McKinley was extraordinarily loving and solicitous of her happiness and well-being, accepting, for example, each of the hundreds of pairs of slippers Ida compulsively knitted for him as if it was the first, and just what he needed. The President insisted that she sit with him at state dinners, and if she slipped into a seizure, as she frequently did, McKinley would calmly cover her head with a large napkin until her contortions passed, then lift it off as if nothing had happened.

When he was shot twice by an assassin, the President’s first thoughts were of Ida. “My wife, be careful, Cortelyou, how you tell her …oh, be careful,” he said to the aide who rushed to assist him.

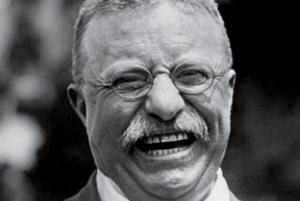

Theodore Roosevelt

The most unusual, dynamic, likable, eccentric and American of our Presidents, the irrepressible Teddy, has too much lore and jaw-dropping tales connected with him to do his legacy justice here. Has any President rebounded from a tragedy like the deaths of his mother and wife on the same night—Valentine’s Day—in the same house? Can any match TR’s crazy/courageous stunt of continuing to give a campaign speech after being shot in the chest by a would-be assassin? (The bullet was deflected by the thickly folded speech itself in Teddy’s breast pocket, giving the ultimate showman the chance to dramatically unfold the bloody thing in front of his amazed audience).

I can’t pick one, so I’ll use this opportunity to excerpt Roosevelt’s most famous speech, his so-called “Man in the Arena” address in 1910, really titled “Citizenship In A Republic” and delivered at the Sorbonne, in Paris, France. I’ve criticized the way this speech is often used by others, essentially to stifle legitimate criticism by saying, “What have you done that gives you standing to find fault with me?” That’s a lazy cop-out, especially for someone in public service, and is too close to other similar tactics, like arguing that only military veterans can make decisions involving war and peace.

The speech, however, is relevant to every one of the men listed in this series of posts, and it is the essence of Teddy Roosevelt.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat. Shame on the man of cultivated taste who permits refinement to develop into fastidiousness that unfits him for doing the rough work of a workaday world. Among the free peoples who govern themselves there is but a small field of usefulness open for the men of cloistered life who shrink from contact with their fellows. Still less room is there for those who deride of slight what is done by those who actually bear the brunt of the day; nor yet for those others who always profess that they would like to take action, if only the conditions of life were not exactly what they actually are. The man who does nothing cuts the same sordid figure in the pages of history, whether he be a cynic, or fop, or voluptuary. There is little use for the being whose tepid soul knows nothing of great and generous emotion, of the high pride, the stern belief, the lofty enthusiasm, of the men who quell the storm and ride the thunder. Well for these men if they succeed; well also, though not so well, if they fail, given only that they have nobly ventured, and have put forth all their heart and strength. It is war-worn Hotspur, spent with hard fighting, he of the many errors and valiant end, over whose memory we love to linger, not over the memory of the young lord who “but for the vile guns would have been a valiant soldier.”

William Howard Taft

According to Indiana Senator James Watson, our fattest President “…simply did not and could not function in alert fashion… Often while I was talking to him after a meal, his head would fall over on his breast and he would go sound asleep for 10 or 15 minutes. He would waken and resume the conversation, only to repeat the performance in the course of half an hour or so.” President Taft was also seen snoozing at operas, funerals, and—especially—church services.”

Today, doctors believe that Taft suffered from Obstructive Sleep Apnea, or OSA, especially since the symptoms abated after he lost 70 pounds following the Presidency. From “Taft and Pickwick: Sleep Apnea in the White House” by John G. Sotos, MD:

Taft had three major risk factors for OSA :he was male, severely obese, and had a “short. . . generous” neck. His size-54 pajamas had a neck size of 19 inches. His body habitus exhibited central obesity…

Taft had two signs of OSA: excessive daytime somnolence and snoring. He may also have been polycythemic: his face was described as “ruddy” and “florid.” Systemic hypertension is a known complication of OSA, albeit common in the general population. Most importantly, Taft’s somnolence correlated with his weight. Taft’s remarkable weight loss after the presidency produced an equally remarkable improvement in his somnolence, blood pressure and, likely, survival.

In October 1910, President Taft was 53 years old, weighed 330 pounds, and snored. With these data, the model of Viner et al. predicts a 97% chance that Taft had sleep apnea…The nature of Taft’s sleeping difficulty in 1913 is unclear. Although OSA may masquerade as insomnia, heart failure is another possibility, given Taft’s “weak heart” and “panting for breath at every step.”

…Any combination of hypertension, obesity, and OSA could have caused heart failure. The reasons for his transiently decreased somnolence in June 1909 are unclear; there are reports of exercise without weight loss improving sleep apnea.

OHS has been known as the “Pickwickian syndrome” since 1956. Before (and after) the noso-logic separation of OSA from OHS in 1965,69,70 it was common to call any sleepy obese patient “Pickwickian.” Biographers have entertained whether Taft had Pickwickian syndrome, but more strongly hold that a psychological need to escape anxiety and strife caused his sleepiness. This seems unlikely because Taft’s somnolence was initially distressing, was involuntary, correlated better with his weight than his happiness, and was so profound that other psychopathology would likely have been manifest.

Thus, I conclude that OSA is the most probable explanation for Taft’s hypersomnolence. Except for periods associated with successful dieting (1906 to mid-1908, and perhaps briefly in 1909), he was likely afflicted from approximately 1900, when he started gaining weight in the Philippines, into 1913, when he started his post-presidency weight loss. He appears to have become symptomatic at approximately 300 lb. Based on Taft’s history of falling asleep during tasks requiring active attention, such as card playing and signing documents, he would be classified as having severe OSA syndrome.

Woodrow Wilson

To me the most amazing thing about Woodrow Wilson is how long the liberal historian establishment led by Kennedy hagiographer Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. managed to have him rated as one of the greatest American Presidents. (I believe his is the closest match for Barack Obama, though it’s still not all that close.) Wilson was smart, credentialed and a progressive, and had a lot of wonderful theories and aspirations, but good intentions pave the road to Hell, as they say, and Woodrow’s Presidency is a cautionary tale.

He promised to keep us out of the Great War, and then right after being elected on the promise, got us into it. His administration then prosecuted scores of radicals and anti-war dissenters, sentencing them to long jail terms for violations of the Espionage Act and the Sedition Act. Once the war was won, Wilson had grand plans for a new international organization to prevent future wars, and allowed himself to be out-maneuvered by vengeful European leaders to agree to a punitive, brutal treaty in Versailles that seeded a worse war, all so his baby would be birthed. Then he didn’t have the political skills to get the treaty and its League of Nations approved by Congress. This precipitated a crippling stroke, and he allowed his wife and doctor to secretly run the country rather than allow his Vice President to take over.

And yet none of this touches the real disgrace of Wilson’s tenure.

Woodrow Wilson was a white supremacist, racist to the bone. He believed that interracial marriage would “degrade the white nations.” He showed “Birth of a Nation” at the White House and pronounced it his favorite film, and his policies brought Jim Crow traditions back to Washington, D.C., after they had been effectively banned by Roosevelt and Taft. The Postal Service and the Treasury Department were beginning to integrate, so Wilson put an end to that, as he stocked his cabinet with Southern racists like himself. At parties, Wilson amused his guests by singing songs that mocked blacks and telling minstrel show jokes in dialect.

He was a progressive for whites only. As President of Princeton, Wilson worked to curb elitism by trying to get rid of the rich kid eating clubs, but when a poor black student at a Virginia Baptist college wrote to make his case for admission, Wilson answered “that it is altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton.”

Wilson was a study in contrasts, to be sure. He was, it is believed, dyslexic, yet is the only President to earn a doctorate. Despite his scholarly appearance, he was reportedly quite a ladies man, and his letters to his two wives when he was wooing them border on pornographic. He was apparently pretty good at singing those minstrel songs, too.

Yup…one of the greats.

Warren G. Harding

Harding is the anti-Wilson. Historians have built the case that he was an amiable, incompetent, over-sexed boob, but his real crime was that he was a real conservative following three progressives. To most of today’s historians, progressive policies equal good, so this makes Harding a bad President, indeed one of the very worst. The record does not back up that assessment.

In his brief tenure (about 2 and a half years, from March 1921 to August 1923, when he died of a heart attack), Harding accomplished a lot. Unfortunately, again thanks to the skewed emphasis of Wilson-worshiping historians, his substantive achievements have been overshadowed by his sexual escapades (Harding affairs bad, JFK affairs…cute!), and the Teapot Dome Scandal, which occurred under his trusting nose and which was uncovered after his death. No doubt about it: that scandal, which was perpetrated by some of Harding’s most trusted associates (Grant deja vu), is a black mark against him. But as historians Ronald Radosh and Allis Radosh show in their upcoming book rehabilitating Harding, there was more to his Presidency than illicit sex in the closet and scandal.

Harding’s fiscal policies brought the country out of the economic depression that resulted from the nation’s unnecessary participation in World War I, as the national debt climbed from $1 billion in 1914 to $24 billion in 1920. The country was already experiencing rising unemployment, and then all the soldiers came home, looking for work. There was deflation, bankruptcies and business closures. Race riots broke out in cities where African-Americans lived in near whites communities.

Once elected, Harding took his campaign pledge to restore America to “normalcy” seriously. He cut government spending and reduced federal income tax rates. The government spent during the war as if “it counted the Treasury inexhaustible,” he told Congress, and added that if that pattern continued, it would result in “inevitable disaster.” Harding established the nation’s first Budget Bureau (the forerunner of today’s Office of Management and Budget) in the Treasury Department as a spending monitoring tool. His polices saw federal spending drop from $6.3 billion in 1920 to $5 billion in 1921 and $3.3 billion in 1922. He championed the Revenue Act of 1921, which eliminated a wartime, anti-business “excess-profits” tax, lowered the top marginal income tax rate from 73 to 58 percent, decreased surtaxes on incomes above $5,000, and increased exemptions for families.

As a result of the economic measures he implemented, unemployment fell from 15.6 percent to 9 percent. The construction, clothing, food, and automobile sectors boomed. From 1921 to 1923, U.S. manufacturing increased by 54 percent. It is fair to say that Harding was doing more than banging White House maids in the closet.

Harding also had guts. He bucked popular opinion and vetoed a World War I veterans bonus that had been promised by Congress, arguing that the national interest came first, and that the state of the economy required that the payment be delayed. No longer could deficit spending, he argued, be used to finance government programs for which the government did not have the funds. Imagine a President saying that today. What an idiot!

Harding also was determined to reverse Wilson’s racist policies, and to lead the nation to full acceptance of civil rights for all. He his support behind a federal anti-lynching law (FDR wouldn’t back such a measure later, for fear of alienating Southern Democrats). Democrats in the House and Senate sent the measure to defeat, as they did Harding’s proposal for the establishment of a biracial commission that would have investigated lynching and such abuses of electoral law as literacy tests and other schemes to disenfranchise black voters. Harding ordered his Cabinet to appoint black Republicans to key positions. He announced his intention to appoint “leading Negro citizens from the several states to more important official positions than were heretofore accorded to them, ” and appointed five African-Americans to jobs in the State Department; three in Treasury, one in the Justice Department, four in Interior, and one each in the Navy, Post Office, and Commerce Department. This was not enough to satisfy the black leaders who had endorsed him during the campaign, but it was a major improvement and a significant step forward out of Wilson’s racist vision for society.

In October of 1921,President Harding gave his “Birmingham speech,” in which he called for equal educational opportunity and an end to the disenfranchisement of black voters. Reporters wrote that white section of the audience listened in stony silence, while black Americans, standing in a roped-off segregated section, cheered.

Harding did not oppose segregation, but his support for civil rights still represented tremendous cultural progress.

Harding freed the political prisoners incarcerated by the Wilson, including Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs, a political prisoner by any definition. He even invited Debs to come to the White House before returning home, and to celebrate his freedom on Christmas Eve with the Hardings. He wrote, “We cannot punish men in America for the exercise of their freedom in political and religious belief.”

There’s an intriguing possibility that Harding had African-American ancestry. He was teased as a child because of such rumors, and some historians have written that there may have been truth to them. The Harding family was accepted by neither white or black communities in Blooming Grove, Ohio, and this made an impression on Warren, who as an adult sought membership in every fraternal and community organization he could find. The contacts he made in these groups ultimately formed the foundation of his political career.

So perhaps Warren G. Harding was the first black President…and the best one so far.

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge is another figure whose reality was at odds with his popular image. For example, “Silent Cal” gave almost as many radio addresses as Franklin Roosevelt. He was also a cut-up: he liked to ring for White House servants and hide in the closet before they arrived.

Coolidge’s most important contribution to our political culture came before he was President, when as Governor of Massachusetts he was faced with the Boston Police Strike of 1919. 75% of the police force left work, and violent mobs of looters terrorized Boston for two nights. Coolidge called in the entire state militia, condemned the strikers as traitors, and declared,“There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”

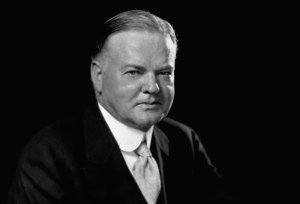

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover was a great man in the wrong place, at the wrong time, as a Depression he didn’t make and couldn’t stop made him a national villain, which is an injustice and a tragedy: it would be hard to be less of a villain than Herbert Hoover:

- Herbert Hoover rose to public prominence during World War I as the Chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, a non-profit, multi-national, non-governmental organization that provided food for more than 9,000,000 Belgian and French civilians trapped behind the front lines.

- In 1923, Herbert Hoover founded the American Child Health Association, an organization dedicated to raising public awareness of child health problems throughout the United States. Mr. Hoover served as the president of the ACHA until 1928.

- After World War II, Hoover initiated a school meals program in the American and British occupation zones of Germany, beginning on April 14, 1947. The program served 3,500,000 children aged six through 18. The program provided a total of 40,000 tons of American food, and was called the Hooverspeisung (Hoover meals).

- He chaired two Commissions on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government, one under President Truman and the other under President Eisenhower. The Hoover Commissions studied the organization and methods of operation of the Executive branch of the Federal Government, and recommended changes to promote economy, efficiency, and improved service.

- Hoover served as Chairman of the Boys’ Clubs of America from 1936 until his death in 1964.

- Herbert Hoover was nominated five times for the Nobel Peace Prize – in 1921, 1933, 1941, 1946 and 1964.

Oh, and by the way, he was a President, too.

All of the Presidents (except FDR) in this last section were alive and kicking while I was, and so to me they are both more real and less fascinating to some extent. Familiarity breeds, if not contempt, a tendency not to idealize. These leaders are no more flawed than their predecessors, they just seem that way thanks to mass media.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Three terms plus, a World War, a Depression, a transformative Presidency and an epic life spent in public service: FDR is another President who can’t be summed up in an anecdote, one book, or a hundred. He accomplished enough great things to be a deserving icon; he committed enough wrongs to be judged a villain. (He was pretty clearly a sociopath, but a lot of great leaders are, including a fair proportion of ours, including some of the best.) The only completely unfair verdict on this Roosevelt is not to acknowledge the importance and complexity of his life. Here are some of my favorite items about him:

- FDR wrote down a plan when he was still in school outlining the best way for him to become President. The plan was essentially to follow his distant cousin Theodore’s career steps: Harvard, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Governor of New York, Vice-Presidential candidate, and President. (He skipped “Rough Rider.”) Amazingly, he followed it, and it worked.

- Conventional wisdom holds that FDR’s polio transformed his character, and that without that crisis and challenge he would have been content to be a rich dilettante. I doubt it, but there is no question that he fits the Presidential survivor template, and that his ordeal made him stronger, more formidable and more determined.

- Many Presidents had strong mothers, especially, for some reason, many of our Chief Executives from Roosevelt to Obama. Franklin’s mom, however, wins the prize. It’s amazing Eleanor didn’t murder her. But Mrs. Roosevelt is why Eleanor was there in the first place: all of our Presidents raised by strong mothers married very strong wives.

- If a computer program were designed to create the perfect American leader, it would give us FDR. He was the complete package; his charisma, charm and power radiate from recordings and films that are 90 years old. That smile! That chin! That head! That voice! He is one of the very few Presidents who would be just as popular and effective today as the era in which he lived.

- And just as dangerous. FDR is also a template for an American dictator, which, I believe, he would have been perfectly willing to be. It’s no coincidence that Franklin was the only President to break Washington’s wise tradition of leaving office after two terms.

- Political and philosophical arguments aside, at least four of Roosevelt actions as President were horrific, and would sink the reputation of most leaders: 1) Imprisoning Japanese-Americans (and German-Americans, too); 2) Ignoring the plight of European Jews as long as he did, when it should have been clear what was going on; 3) Handing over Eastern Europe to Stalin, and 4) Knowing how sick he was, giving little thought or care to who his running mate was in 1944.

- Balancing all that, indeed outweighing it, is the fact that the United States of America and quite possibly the free world might not exist today if this unique and gifted leader were not on the scene. Three times in our history, the nation’s existence depended on not just good leadership, but extraordinary leadership, and all three times, the leader we needed emerged: Washington, Lincoln, and Franklin. I wouldn’t count on us being that lucky again.

I left the bulk of reflection about the character and leadership style of Theodore Roosevelt to one of Teddy’s own speeches to embody, and I’ll do the same for his protege.

On September 23, 1932, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt gave a speech at Manhattan’s Commonwealth Club. (Everyone, conservative, liberal or moderate, should read it….here.) It was a defining statement of progressive principles and modern liberalism, redefining core American values according to the perceived needs of a changing nation and culture. It is a radical speech, and would be regarded as radical by many today, even after much of what Roosevelt argued was reflected in the policies of the New Deal.

After sketching the origins and progress of the nation to the present, he flatly stated that the Founders’ assumptions no longer applied:

A glance at the situation today only too clearly indicates that equality of opportunity as we have know it no longer exists. Our industrial plant is built; the problem just now is whether under existing conditions it is not overbuilt. Our last frontier has long since been reached, and there is practically no more free land. More than half of our people do not live on the farms or on lands and cannot derive a living by cultivating their own property. There is no safety valve in the form of a Western prairie to which those thrown out of work by the Eastern economic machines can go for a new start. We are not able to invite the immigration from Europe to share our endless plenty. We are now providing a drab living for our own people….

Just as freedom to farm has ceased, so also the opportunity in business has narrowed. It still is true that men can start small enterprises, trusting to native shrewdness and ability to keep abreast of competitors; but area after area has been preempted altogether by the great corporations, and even in the fields which still have no great concerns, the small man starts with a handicap. The unfeeling statistics of the past three decades show that the independent business man is running a losing race. Perhaps he is forced to the wall; perhaps he cannot command credit; perhaps he is “squeezed out,” in Mr. Wilson’s words, by highly organized corporate competitors, as your corner grocery man can tell you.

Recently a careful study was made of the concentration of business in the United States. It showed that our economic life was dominated by some six hundred odd corporations who controlled two-thirds of American industry. Ten million small business men divided the other third. More striking still, it appeared that if the process of concentration goes on at the same rate, at the end of another century we shall have all American industry controlled by a dozen corporations, and run by perhaps a hundred men. Put plainly, we are steering a steady course toward economic oligarchy, if we are not there already.

Clearly, all this calls for a re-appraisal of values.

So Franklin Roosevelt re-appraised them:

…The Declaration of Independence discusses the problem of Government in terms of a contract. Government is a relation of give and take, a contract, perforce, if we would follow the thinking out of which it grew. Under such a contract rulers were accorded power, and the people consented to that power on consideration that they be accorded certain rights. The task of statesmanship has always been the re-definition of these rights in terms of a changing and growing social order. New conditions impose new requirements upon Government and those who conduct Government….

I feel that we are coming to a view through the drift of our legislation and our public thinking in the past quarter century that private economic power is, to enlarge an old phrase, a public trust as well. I hold that continued enjoyment of that power by any individual or group must depend upon the fulfillment of that trust. The men who have reached the summit of American business life know this best; happily, many of these urge the binding quality of this greater social contract.

The terms of that contract are as old as the Republic, and as new as the new economic order.

Every man has a right to life; and this means that he has also a right to make a comfortable living. He may by sloth or crime decline to exercise that right; but it may not be denied him. We have no actual famine or dearth; our industrial and agricultural mechanism can produce enough and to spare. Our Government formal and informal, political and economic, owes to everyone an avenue to possess himself of a portion of that plenty sufficient for his needs, through his own work.

Every man has a right to his own property; which means a right to be assured, to the fullest extent attainable, in the safety of his savings. By no other means can men carry the burdens of those parts of life which, in the nature of things, afford no chance of labor; childhood, sickness, old age. In all thought of property, this right is paramount; all other property rights must yield to it. If, in accord with this principle, we must restrict the operations of the speculator, the manipulator, even the financier, I believe we must accept the restriction as needful, not to hamper individualism but to protect it….

The final term of the high contract was for liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We have learned a great deal of both in the past century. We know that individual liberty and individual happiness mean nothing unless both are ordered in the sense that one man’s meat is not another man’s poison. We know that the old “rights of personal competency,” the right to read, to think, to speak, to choose and live a mode of life, must be respected at all hazards. We know that liberty to do anything which deprives others of those elemental rights is outside the protection of any compact; and that Government in this regard is the maintenance of a balance, within which every individual may have a place if he will take it; in which every individual may find safety if he wishes it; in which every individual may attain such power as his ability permits, consistent with his assuming the accompanying responsibility….

Faith in America, faith in our tradition of personal responsibility, faith in our institutions, faith in ourselves demand that we recognize the new terms of the old social contract. We shall fulfill them, as we fulfilled the obligation of the apparent Utopia which Jefferson imagined for us in 1776, and which Jefferson, Roosevelt and Wilson sought to bring to realization. We must do so, lest a rising tide of misery, engendered by our common failure, engulf us all. But failure is not an American habit; and in the strength of great hope we must all shoulder our common load….

Before “We have nothing to fear but fear itself” and the rest, FDR delivered one of the most influential and important speeches in U.S. history. Like the Commonwealth Speech or hate it, we must concede that Roosevelt’s ideas still drive our public policy debates today.

Harry S Truman

Like many of the Vice Presidents who reached the top of our government organizational chart upon the death of a President, Harry Truman would have never reached the office under normal circumstances. He was short, he was unimpressive physically, he was an indifferent speaker, and neither his career nor his character appeared to show special promise. But like TR and Arthur, and later, Lyndon Johnson, Truman was up to the job, and it’s a good thing he was.

The key to his success was that he was not afraid to make decisions. This is the single most important trait of good leaders. Often any decision is better than a tardy or delayed one, and easily a third of our Presidents lacked Truman’s courage, resolve, and accountability.

The most difficult, controversial and important decision that Truman had to make was his decision to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima. An interesting exercise is to try to discern which of our Presidents would have made the same decision under the same circumstances. Some are easy calls. Both Roosevelts–sure. Ike? Yes. LBJ? Yes. Nixon? Definitely. Reagan? Of course. Probably both Bushes, definitely W. Grant? You bet. Polk? Oh yes. Jackson wouldn’t have just dropped the A bomb, he would have enjoyed it.

Lincoln? I wonder.

The definite no-bomb group would include Jefferson, the Adamses, Buchanan, Taft, Wilson, Hoover…Jimmy Carter would still be considering all the options 40 years later. The most intriguing maybes are Washington, Kennedy and Clinton.

It would make a good parlor game. Back to the real decision: the Truman Library has various records of Truman’s thought process leading up to and after the decision:

-

Secretary of War to Harry S. Truman, July 30, 1945, with Truman’s handwritten note on reverse, regarding the readiness of the atomic bomb and Truman’s approval to release it on Hiroshima. Papers of George M. Elsey. (2 pages)

- Diary entry of Harry S. Truman, July 17, 1945, describing his first meeting with Stalin at Potsdam and expressing optimism in “handling” Stalin, as well as a reference to the atomic bomb. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File. (1 page)

- Diary entry of Harry S. Truman, July 18, 1945, recounting meeting with Stalin and Truman’s intention of telling him about the bomb, as well as mentioning that the Japanese will surrender once Manhattan (the atomic bomb) is released on them. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File. (2 pages)

- Diary entry of Harry S. Truman, July 25, 1945, in which he reflects on the atomic bomb tests and the destructiveness of it, and the plan for using the bomb on military targets only. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File. (2 pages)

- Letter, Harry S. Truman to Bess Wallace Truman, July 31, 1945, describing negotiations among the Allies in Berlin. Papers of Harry S. Truman: Family, Business, and Personal Affairs File. (4 pages)

- Correspondence between Richard Russell and Harry S. Truman, August 7 and 9, 1945, regarding the situation with Japan. Papers of Harry S. Truman: Official File. (5 pages)

- .Correspondence between Samuel M. Cavert and Harry S. Truman, August 9 and 11, 1945, regarding the situation with Japan. Papers of Harry S. Truman: Official File (3 pages)

- Handwritten speech draft, December 15, 1945, detailing Truman’s feelings on his decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File (14 pages)

Truman does not reveal himself as a deep thinker, and this can be an asset with decisions like this. As Ellie (Laura Dern) says to John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) in “Jurassic Park” when everything is falling apart and people are getting eaten, “You can’t think your way through this, John. You have to feel it.” The best leaders have an instinct for what is needed, and do it. Here was Truman’s letter to a critic about the issue 18 years later. It’s not especially persuasive; it’s a jumble of the things that were going through his mind. What matters is that he made the decision, and was able to sleep that night.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

When I was a boy growing up (allegedly) in Boston, there was a popular daytime kids show during the week called “The Small Fry Club” hosted by a man named Bob Emory, who called himself “Big Brother.” A regular feature of the show, which was performed, Howdy Doody-style, before a grandstand of kids, was the Toast to the President. As the camera focused on the portrait of President Eisenhower above and the martial strains of “Hail to the Chief” wafted over the proceedings, Bob, the kids, and all of us at home lifted a glass of milk to Ike. I kid you not.

Eisenhower is one President whose ranking has risen steadily since he left office, as the job he seemed to do so effortlessly has defeated so many of his successors, as more has been learned about his “hidden hand” Presidency, and as the Fifties have become better understood as the perilous minefield of Cold War traps and threats that it was.

Ike shares an oddity with Grant, Wilson and Cleveland: they all switched their middle names with their more common first names (Hiram, David, Thomas and Stephen, respectively) early in life to be more distinctive. Distinctive names are also Presidential: starting with #12, we’ve had no Michaels or Roberts, but a Millard, two Franklins, an Abraham, Ulysses, Rutherford, Chester, Grover, Theodore, Woodrow, Warren, a Lyndon, the formally nicknamed Bill and Jimmy, and Barack. Ike knew what he was doing.

It wasn’t until well after he left office that it became known how often the former Allied Commander was willing to engage in brinksmanship to resolve international crises, threatening nuclear strikes at a time when the U.S. had no real equal in nuclear arsenals. The tally is at least three: against China to end the Korean War, against Russia to get it to back off during the Suez crisis, and China again when Taiwan was threatened. Eisenhower could draw a red line like no other President before or since, thanks to the respect and credibility he had earned during World War II. Nobody thought he was bluffing, and nobody was willing to call his bluff if he was.

Those were the days.

I think I’ll get a glass of milk.

I feel a toast coming on…

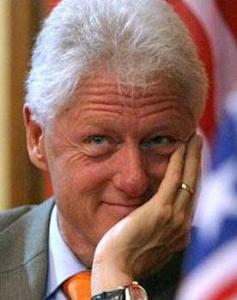

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

JFK’s story is made for alternate histories. His father was a bootlegging, Nazi sympathizing scoundrel; the family legacy to its men was misogyny and self-indulgence. Shady deals helped make Jack President, and he was a mass of deception; the truth could have caught up with him in a million ways had he lived. Kennedy had intelligence, wit and ability, but he was also a sick man shot full of enough drugs to confuse a race-horse, a virtual Presidential junkie. His sexual appetite made Harding look ascetic. If one of his affairs, especially the ones with the mob boss’s moll or the Israel double-agent, had become public, he might have been impeached.

At the time of his death, the legacy of Kennedy’s years in office, other than the lies, stood at the space program, the Peace Corps, and a welter of foreign policy blunders that the Kennedy spin machine managed to sufficiently blind the public about so that he escaped the blame he deserved. What kind of President might he have been if he lived, and what would the country have been like as a result? This is Stephen King territory: JFK had the capacity for growth; he also was reckless, ruthless, and arrogant. Any alternate history from an ascendant, peaceful, re-energized world power to a smoldering parking lot is plausible.

I have published this story before. Here is what I think of when I muse about what we don’t know about John Fitzgerald Kennedy:

Several years ago, I had just completed an ethics seminar for the DC Bar. One of the issues I discussed was the lawyer’s ethical duty to protect attorney-client confidences in perpetuity, even after the death of the client. An elderly gentleman approached me, and said he had an important question to ask. He was retired, he said, and teased that I would want to hear his story. I don’t generally give out ethics advice on the fly like this, but I was intrigued.

“My late law partner, long before he began working with me, was Joseph P. Kennedy’s “‘fixer,'” he began, hooking me immediately. “Whenever Jack, Bobby or Teddy got in trouble, legal or otherwise, Joe would pay my partner to ‘take care of it,’ whatever that might entail. Well, my partner died last week, and when I saw him for the last time, he gave me the number of a storage facility, the contract, and the combination to the lock. He said that I should take possession of what was in there, and that I would know what to do.

“Well, I did as he said. What I found were crates and boxes of files, all with labels on them relating to the three Kennedy brothers. There are files with the names of famous actresses on them, and some infamous figures too. There is an amazing amount of stuff, and I have to believe that it is a treasure trove for historians and biographers. I am dying to read it myself. So my question to you is this…

“Jack, Bobby, Ted and old Joe are all dead now, and my partner is dead too. What did my late partner mean when he said I would know what to do?”

And I sighed.

“I would love to know what’s in those files myself.” I said. “But assuming that he meant that you would know the right thing to do and trusted you to do it, your only ethical course is to protect those confidences that Joe Kennedy had been assured would always be between him and his attorney. His surviving family members don’t even have a right to know them, and it’s quite possible, even likely, that Joe wouldn’t want them to know what his boys did that required a “fixer.”

“The only ethical course for you is to destroy those files. Unfortunately.”

“I was afraid you would say that,” he said. “Thank you. That’s exactly what I’ll do.”

And he walked away, shaking his head.

Lyndon Baines Johnson

Lyndon Johnson’s mother changed the spelling of his name from Linden to Lyndon, she wrote, because it would look better on a ballot. Johnson had all the tools to be a great President but not enough of the assets that get Presidents elected. He was wily, smart, gutsy, ruthless when he had to be, a canny negotiator, charmer of both sexes and a natural leader. Unfortunately, he was Lincoln-ugly in a mass media society, and a horrible public speaker. Able as he was, Johnson was never going to be elected President, and then, magically, he was one, the beneficiary of Kennedy’s need to win the Lone Star State (despite his utter disdain for Johnson) and an assassin’s bullet. Suddenly Johnson had power, and he knew how to use it. For the third time (the others: Teddy and Harry), an accidental President had the chops for the big job.

Of course, we now know that LBJ’s story became a Shakespearean tragedy. My next door neighbor in Arlington Massachusetts was Harvard American Government scholar, Professor Robert McCloskey. He was a New Deal liberal, and he loved Johnson. He was convinced that he would be as transformational as FDR. Then the war in Vietnam got ugly; and it derailed LBJ’s administration and McCloskey’s dream.

I remember hearing him shouting in discussions with my father how LBJ was blowing his great opportunity, dissipating his support, tearing the country in two, and he couldn’t understand it. The professor died of cardiac arrest while Johnson was in office. My father believed that his frustration over Johnson and Vietnam killed him.

The problem is that we are all human, and being human in the wrong ways at the wrong time is a constant danger for leaders. Johnson was a Texan to his marrow, and the plight of South Vietnam made him identify it with the Alamo. I wonder if non-Texans understand the deep reverence Texans have for that battle and the heroism of the men there. For Johnson, that identification framed the Southeast Asian fiasco in a way that made it personal, clouded his judgment, and led to a national, cultural and professional catastrophe.

When Johnson died, his body lay in state in the Capitol, and lines wound around the Capitol grounds as citizens, many of them African-Americans, waited for hours to bass by his bier and pay their respects. Was any President so revered and so despised by so many simultaneously?

Richard Nixon

Luck evens out over time. As fortunate as the United States was to have Washington, Lincoln and Roosevelt, great leaders all, at the ready when the nation needed their genius, it was spectacularly unlucky to have two of its most qualified and able leaders doomed to failure because they served in times that exploited their vulnerabilities.

Maybe nothing could save Richard Nixon. He came to office by far the most qualified man ever to become President. He had watched and learned from one of the best, Eisenhower, and also had performed the duties of the office during the multiple occasions Ike was hospitalized or convalescing. Nixon was bright, maybe brilliant; he had Wilson’s knowledge of politics, Lincoln’s tactical acumen and Johnson’s audacity. He was not, however, a great man, and a great leader has to be one. Eisenhower didn’t like him or trust him: Ike’s tepid endorsement of his own Vice-President lost Nixon the 1960 election as much or more than Democratic ballot-stuffing. As usual, Ike was right.

Were it not for Watergate, people a century from now might look at Nixon’s record and wonder, “Why did the news media hate this man? He was more liberal than a lot of Democrats. He did some great things.” Just as there is no explaining charisma and charm, however, it is impossible to understand the stench of insecurity and void of trustworthiness some people carry. Nixon was a lonely, insecure boy who grew to be an almost friendless, paranoid man. All his ability, intelligence and experience couldn’t compensate for the handicap of his hollow character. That is what brought him to ruin. If it had not been Watergate, it would have been something else.

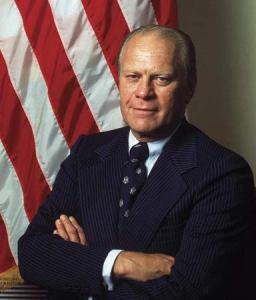

Gerald Ford

My thesis in American Government was on Presidential character, and the first revelation of my research was that these guys, as a group, were weird. They were unusual as children; they knew they were different; they sought power to compensate for other deficits; they saw themselves as being placed on earth for great things. Many felt driven by impossible role models, often their fathers. By the time I completed my thesis, it was clear to me that the typical President of the United States was not psychologically healthy, and was definitely not normal.