sacrifice

Comment Of The Day: “No, Insurance Companies Treating People With Pre-Existing Conditions Differently From Other Customers Is Not ‘Discrimination’.”

There have been a lot of lively and articulate debates on Ethics Alarms since it began in late 2009, but I don’t know if any post has generated more thoughtful, informed and enlightening comments than this one. Many of them, and I mean ten or more, are Comment of the Day worthy. I would post them all, but it’s more efficient to just send you to the post. I’m very proud of Ethics Alarms readers on this one. It’s an honor to have followers so astute and diverse.

I chose Spartan‘s comment over the others in part because it was the most overtly about ethics, balancing and altruism. Plus the fact that she gets a lot of flack here, and yet perseveres with provocative comments that are well-reasoned and expressed. She is an excellent representative of all the commenters that add so much to this blog.

Here is Spartan’s Comment of the Day on the post, No, Insurance Companies Treating People With Pre-Existing Conditions Differently From Other Customers Is Not “Discrimination.”

The biggest problem — single payer is a jobs killer. I’ll admit that. Tens of thousands of people will have to find new jobs. Of course, there’s a flip side to this issue. Is it moral to sustain an industry that only benefits the rich and those who have access to employer-sponsored health care?

If we are going to get anywhere in this political debate, we have to be honest. Single payor is not sunshine and rainbows for all. Many people will have to find new jobs. Not everybody will love the care that they are provided. Medical students might decide to become stockbrokers instead because they will not make as much money. (On the plus side, the risk for med mal will go down so maybe there will not be a mass exodus.)

Another truth: a single payer plan will hurt the upper middle class the most. People like me. Because under single payer, I undoubtedly will have to pay more in taxes (the only way it could work), but I most likely will get a lower standard of care down the road. So, I imagine many people like me will go out and buy private insurance to sit on top of government provided medical care. So now I am even out more money. (Similarly, I don’t like my government provided education, so I pay money out of pocket for my kids’ school.)

While acknowledging all of this, I would still vote for single payer. In my view, it’s not ethical to let people die so other people can have jobs. That’s my position. If it means we can never go on another vacation or eat out again, it is more important to me that everyone have access to basic health care.

The “Transitioning” Female Wrestler: A Failure Of Ethics And Common Sense

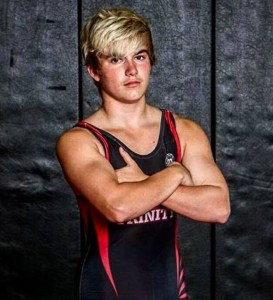

Mack Beggs is a competitive wrestler at Euless Trinity High School, and also is a biological female more than a year into the process of “transitioning” to male. Beggs just won his third consecutive girls’ wrestling tournament victory in the 110-pound weight class. I’ll call him “he” because that is what the student wants to be called, and he, in great part due to the male steroid treatment he has been undergoing, is now 55-0 on the season. All of his opponents have been high school girls who are not taking steroids, and unlike Mack, do not intend to become, for all intents and purposes, male.

While Beggs says he wants to wrestle in the boy’s competitions, the University Interscholastic League rules use an athlete’s birth certificate to determine gender, a measure that makes sense in most cases, just not this one. (See: The Ethics Incompleteness Principle) The rules prohibit girls from wrestling in the boys division and vice versa, and rules are rules. If you are a rigid, non-ethically astute bureaucrat, you follow rules even when you know that they will lead to unjust, absurd results, like Mack’s 55-0 record in matches.

The rules also say that taking performance enhancing drugs like the testosterone that has given Beggs greater muscle mass and strength than his female competitors is forbidden, but UIL provides an exception for drugs prescribed by a doctor for a valid medical purpose. After a review of Beggs’ medical records, the body granted him permission to compete while taking male steroids—compete as a girl, that is. Rules are rules!

One athletic director, after watching Beggs crush a weaker female competitor who left the ring in tears, asked for his name not to be used as he commented to reporters, and opined that “there is cause for concern because of the testosterone,” and added, “I think there is a benefit.”

Really going out on a limb there, sport, aren’t you?

Here, let me help.

This is an unfair, foolish, completely avoidable fiasco brought about by every party involved not merely failing to follow ethical principles and common sense, but refusing to. Continue reading

Ethics Hero: Hillary Clinton

The criteria for an Ethics Hero honor here includes doing the ethical thing despite significant countervailing non-ethical considerations, and often at some personal sacrifice. It was Bill Clinton’s duty to be present at Donald Trump’s Inauguration yesterday, but not Hillary’s. While defeated Presidential candidates usually attend, they sometimes don’t, especially when they feel particularly aggrieved byt the way the successful campaigns against them were handled. Recent inauguration no-shows include Mitt Romney and Michael Dukakis, both of whom felt, with some justification, that they had been ill-treated on their way to defeat. Four Presidents didn’t even attend the swearing in of their successors: John Adams (bitter), John Quincy Adams (bitter, and Andrew Jackson hadn’t attended his inauguration, so there!) Andrew Johnson (impeached), and Richard Nixon (persona non grata).

Nobody, especially her supporters, would have blamed Mrs. Clinton if she had passed. However, it was important that she be there, as her presence symbolized acceptance of the result and the orderly transfer of power as much as Barack Obama’s presence did. She came, she was seen, and it was the right thing to do.

It could not have been easy or pleasant. Some in the audience were heard to chant “Lock her up!” when her name was announced. (See: “A Nation of Assholes”) Bill may have embarrassed her by being caught on video seeming to ogle Ivanka Trump. (I wrote a satirical song about Clinton ogling Julie Eisenhower at Nixon’s funeral in 1994, but that was a joke. Good old Bill. ) Jerkish journalists pestered Hillary with the predictable and needless questions: “Madame Secretary, how does it feel to be here today?” and “How are you feeling, Madame Secretary?” Ann Althouse made me laugh out loud with her comment:

What’s she supposed to say? I’ll say it for her: How the fuck do you think it feels?

Holiday Encore: “Christmas: the Ethical Holiday”

I googled “Christmas ethics” yesterday, and guess what came up first. This Ethics Alarms post, from December 25, 2010.

I fix a couple of things, but it is basically the same. If I were writing it anew, I might not use the loaded term “war on Christmas,” which those who are trying to shove Christmas out of the national culture indignantly deny. It isn’t a war, exactly, just a relentless, narrow-minded and destructive effort to take something that has been enduring, healthy, unifying and good, and re-define it as archaic, offensive, divisive, and wrong. Call it the suffocation of Christmas, or perhaps the assassination of Christmas. Whatever one calls it, the process has progressed since 2010.

We’ve discussed on various comment threads quite a bit about how Christmas music has almost vanished from radio. It has also been effectively banned from public schools, who are terrified of law suits in era when parents might sue over their child being warped by learning “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” “Here Comes Santa Claus!”, another one of Gene Autry’s liveliest Christmas hits, one he wrote himself(unlike “Rudolph”), has been declared musica non grata everywhere but on nostalgia satellite radio. It is such an up-beat song; Bing Crosby sings it with the Andrews Sisters on his iconic “Merry Christmas!” album. Why is it unwelcome today? It is unwelcome because the lyrics say we are “all God’s children,” and ends with “Let’s give thanks for the Lord above.” Can’t have that.

The ascendant attitude toward Christmas is both anti-religious and non-ethical. In my neighborhood, there are far more Star Wars Christmas figures, including Yule Darth Vader ( though thankfully not the 18-ft. Hammacher-Schlemmer version pictured above) and Christmas Storm Troopers, than any suggestion of peace, good will or love. Even these non-sectarian displays are too much for the Diversity Fascists, like this guy:

Such people believe that a healthy national culture embracing love, charity, generosity and kindness is disrespectful, and their society-rotting ideology is as much of a threat to our nation as terrorism. I don’t know how to reverse the damage already inflicted on our society, but I do know that we have to try. Reinvigorating Christmas and the ethical values it stands for would be a good start.

Merry Christmas, everyone—and I do mean everyone.

Finally, here’s the post..

The Complete “It’s A Wonderful Life” Ethics Guide [UPDATED AGAIN! ]

Once again, Ethics Alarms re-posts its ethics guide to Frank Capra’s 1946 masterpiece “It’s A Wonderful Life,”one of the great ethics movies of all time. It was written in 2011, and revised regularly since, including for this year’s version. I suspect we need it more in 2016 than usual.

It is fashionable now, and was even when the film was released, to mock its sentiment and optimism. On one crucial point Capra was correct, however, and it is worth watching the film regularly to recall it. Everyone’s life does touch many others, and everyone has played a part in the chaotic ordering of random occurrences for good. Think about the children who have been born because you somehow were involved in the chain of events that linked their parents. And if you can’t think of something in your life that has a positive impact on someone–although there has to have been one, and probably many—then do something now. It doesn’t take much; sometimes a smile and a kind word is enough. Remembering the lessons of “It’s a Wonderful Life” really can make life more wonderful, and not just for you.

Here we go:

1. “If It’s About Ethics, God Must Be Involved”

The movie begins in heaven, represented by twinkling stars. There is no way around this, as divine intervention is at the core of the fantasy. Heaven and angels were big in Hollywood in the Forties. Nevertheless, the framing of the tale advances the anti-ethical idea, central to many religions, that good behavior on earth will be rewarded in the hereafter, bolstering the theory that without God and eternal rewards, doing good is pointless.

We are introduced to George Bailey, who, we are told, is in trouble and has prayed for help. He’s going to get it, too, or at least the heavenly authorities will make the effort. They are assigning an Angel 2nd Class, Clarence Oddbody, to the job. He is, we learn later, something of a second rate angel as well as a 2nd Class one, so it is interesting that whether or not George is in fact saved will be entrusted to less than Heaven’s best. Some lack of commitment, there—then again, George says he’s “not a praying man.” This will teach him—sub-par service!

2. Extra Credit for Moral Luck

George’s first ethical act is saving his brother, Harry, from drowning, an early exhibition of courage, caring and sacrifice. The sacrifice part is that the childhood episode costs George the hearing in one ear. He doesn’t really deserve extra credit for this, as it was not a conscious trade of his hearing for Harry’s young life, but he gets it anyway, just as soldiers who are wounded in battle receive more admiration and accolades than those who are not. Yet this is only moral luck. A wounded hero is no more heroic than a unwounded one, and may be less competent as well as less lucky.

3. The Confusing Drug Store Incident

George Bailey’s next ethical act is when he saves the life of another child by not delivering a bottle of pills that had been inadvertently poisoned by his boss, the druggist, Mr. Gower. This is nothing to get too excited over, really—if George had knowingly delivered poisoned pills, he would have been more guilty than the druggist, who was only careless. What do we call someone who intentionally delivers poison that he knows will be mistaken for medication? A murderer, that’s what. We’re supposed to admire George for not committing murder.

Mr. Gower, at worst, would be guilty of negligent homicide. George saves him from that fate when he saves the child, but if he really wanted to show exemplary ethics, he should have reported the incident to authorities. Mr. Gower is not a trustworthy pharmacist—he was also the beneficiary of moral luck. He poisoned a child’s pills through inattentiveness. If his customers knew that, would they keep getting their drugs from him? Should they? A professional whose errors are potentially deadly must not dare the fates by working when his or her faculties are impaired by illness, sleeplessness or, in Gower’s case, grief and alcohol.

4. The Uncle Billy Problem

As George grows up, we see that he is loyal and respectful to his father. That’s admirable. What is not admirable is that George’s father, who has fiduciary duties as the head of a Building and Loan, has placed his brother Billy in a position of responsibility. As we soon learn, Billy is a souse, a fool and an incompetent. This is a breach of fiscal and business ethics by the elder Bailey, and one that George engages in as well, to his eventual sorrow. Continue reading

Ethics Quote Of This Day, July 2: The Inscription On the Monument To The First Minnesota Regiment At Gettysburg National Battlefield Park

“On the afternoon of July 2, 1863 Sickles’ Third Corps, having advanced from this line to the Emmitsburg Road, eight companies of the First Minnesota Regiment, numbering 262 men were sent to this place to support a battery upon Sickles repulse. As his men were passing here in confused retreat, two Confederate brigades in pursuit were crossing the swale. To gain time to bring up the reserves and save this position, Gen Hancock in person ordered the eight companies to charge the rapidly advancing enemy. The order was instantly repeated by Col Wm Colvill. And the charge as instantly made down the slope at full speed through the concentrated fire of the two brigades breaking with the bayonet the enemy’s front line as it was crossing the small brook in the low ground there the remnant of the eight companies, nearly surrounded by the enemy held its entire force at bay for a considerable time and till it retired on the approach of the reserve the charge successfully accomplished its object. It saved this position and probably the battlefield. The loss of the eight companies in the charge was 215 killed & wounded. More than 83% percent. 47 men were still in line and no man missing. In self sacrificing desperate valor this charge has no parallel in any war. Among the severely wounded were Col Wm Colvill, Lt Col Chas P Adams & Maj Mark W. Downie. Among the killed Capt Joseph Periam, Capt Louis Muller & Lt Waldo Farrar. The next day the regiment participated in repelling Pickett’s charge losing 17 more men killed and wounded.”

On July 2, 1863, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 262 Union soldiers in the First Minnesota Regiment rushed—which apparently specialized in desperate fighting-–to throw themselves into a breach in the Union line at Cemetery against a greatly superior force, knowing that they were almost surely to die. 215 of them did, but the regiment bought crucial minutes that allowed reinforcements to arrive.

It is perhaps one of the most inspiring of the many acts of courage that day, the second day of the battle that changed the course of the Civil War. I first wrote about the sacrifice of the First Minnesota five years ago, here.

Let’s try to remember.

(A recommendation: Sometime between July 1 and the Fourth ever year, we always watch Ted Turner’s excellent film, which also has one of my favorite film scores. It helps.)

An Unethical Heart-Warming Christmas Story…Dumb, Too

The headline:

“Mom did porn to buy son’s Christmas presents”

The story, as told by the New York Post:

A single mom has been more naughty than nice this year — but all in the spirit of Christmas.

Megan Clara spent the last year starring in porn movies so she could afford everything on her 5-year-old son Ashton’s Christmas list. The 20-year-old UK resident says she was devastated last holiday season when Ashton complained he didn’t have the same expensive presents as his friends. Making nearly $120 a week, she was only able to buy an Etch A Sketch, cuddly toys and new clothes

“Last Christmas I could barely scrape any money together, it was really tough and I couldn’t help but worry Ashton was going to be left out and disappointed” the mom from Portsmouth, England, told Caters News Agency.After seeing an old friend “stripping off,” Clara got in touch with her friend’s photographer. The rest, she says, is history.

“My job’s amazing, I love being in front of the camera,” she said. “My idol is Katie Price, I thought if she can make money by glamor modeling it was worth me giving it a go too – I’m in awe of her.”

The young mom now gets paid $743 per scene and has spent almost $2,200 on her son this Christmas.

“Ashton has wanted a bike for over three years and I’ve finally been able to make his dream come true. It’s an amazing feeling. The only downside is that he now bribes me into buying him toys for being well-behaved,” she said.

The adult film star already received backlash about her chosen profession, but says that “some people are just jealous.”

“I know not everyone agrees with the adult film industry but I’m a great mum, why should it matter what my occupation is,” she said. “I love the excitement and get a rush. Plus it pays well too.”…“This year has been a complete roller coaster and a whirlwind, there’s been ups and downs but now I’ve learned to ignore what other people think.

Here’s what I think, whether Clara cares or not: There is so much wrong with this story that it qualified as a Christmas Kaboom, but my head, in the spirit of Christmas, didn’t want to explode all over the tree. Continue reading

On the Importance Of Christmas To The Culture And Our Nation : An Ethics Alarms Guide

I don’t know what perverted instinct it is that has persuaded colleges and schools to make their campuses a Christmas-free experience. Nor can I get into the scrimy and misguided minds of people like Roselle Park New Jersey Councilwoman Charlene Storey, who resigned over the city council’s decision to call its Christmas tree lighting a Christmas Tree Lighting, pouting that this wasn’t “inclusive,” or the CNN goon who dictated the bizarre policy that the Christmas Party shot up by the husband-wife Muslim terrorists had to be called a “Holiday Party.” Christmas, as the cultural tradition it evolved to be, is about inclusion, and if someone feels excluded, they are excluding themselves. Is it the name that is so forbidding? Well, too bad. That’s its name, not “holiday.” Arbor Day is a holiday. Christmas is a state of mind. [The Ethics Alarms Christmas posts are here.]

Many years ago, I lost a friend over a workplace dispute on this topic, when a colleague and fellow executive at a large Washington foundation threw a fit of indignation over the designation of the headquarters party as a Christmas party, and the gift exchange (yes, it was stupid) as “Christmas Elves.” Marcia was Jewish, and a militant unionist, pro-abortion, feminist, all-liberal all-the-time activist of considerable power and passion. She cowed our pusillanimous, spineless executive to re-name the party a “holiday party” and the gift giving “Holiday Pixies,” whatever the hell they are.

I told Marcia straight out that she was wrong, and that people like her were harming the culture. Christmas practiced in the workplace, streets, schools and the rest is a cultural holiday of immense value to everyone open enough to experience it, and I told her to read “A Christmas Carol” again. Dickens got it, Scrooge got it, and there was no reason that the time of year culturally assigned by tradition to re-establish our best instincts of love, kindness, gratitude, empathy, charity and generosity should be attacked, shunned or avoided as any kind of religious indoctrination or “government endorsement of religion.” Jews, Muslims, atheists and Mayans who take part in a secular Christmas and all of its traditions—including the Christmas carols and the Christian traditions of the star, the manger and the rest, lose nothing, and gain a great deal. Christmas is supposed to bring everyone in a society together after the conflicts of the past years have pulled them apart, What could possibly be objectionable to that? What could be more important than that, especially in these especially divisive times? How could it possibly be responsible, sensible or ethical to try to sabotage such a benign, healing, joyful tradition and weaken it in our culture, when we need it most?

I liked and respected Marcia, but I deplore the negative and corrosive effect people like her have had on Christmas, and as a result, the strength of American community. I told her so too, and that was the end of that friendship. Killing America’s strong embrace of Christmas is a terrible, damaging, self-destructive activity, but it us well underway. I wrote about how the process was advancing here, and re-reading what I wrote, I can only see the phenomenon deepening, and hardening like Scrooge’s pre-ghost heart. Then I said…

Christmas just feels half-hearted, uncertain, unenthusiastic now. Forced. Dying.

It was a season culminating in a day in which a whole culture, or most of it, engaged in loving deeds, celebrated ethical values, thought the best of their neighbors and species, and tried to make each other happy and hopeful, and perhaps reverent and whimsical too. I think it was a healthy phenomenon, and I think we will be the worse for its demise. All of us…even those who have worked so diligently and self-righteously to bring it to this diminished state.

Resuscitating and revitalizing Christmas in our nation’s heart will take more than three ghosts, and will require overcoming political correctness maniacs, victim-mongers and cultural bullies; a timid and dim-witted media, and spineless management everywhere. It is still worth fighting for.

More than five years ago, Ethics Alarms laid out a battle plan to resist the anti-Christmas crush, which this year is already underway. Nobody was reading the blog then; more are now. Here is the post: Continue reading

By fortune’s smiles, I was able to finally meet Charlie last week face to face, as he kindly alerted me that he would be passing through my neighborhood. Finally having personal contact with an Ethics Alarms reader is always a revealing and enjoyable experience, and this time especially so. I think you would all enjoy Charlie; I certainly did. Maybe I need to hold an Ethics Alarms convention.

Here is his Comment of the Day on the post, Comment Of The Day: “No, Insurance Companies Treating People With Pre-Existing Conditions Differently From Other Customers Is Not ‘Discrimination’.”

…The claim that “a free market system” and “freedom of choice” is the solution to all that ails us is a mindless mantra that is only occasionally true, but not always.

It’s important to be clear about when free market solutions are good, and when they are not. It’s not all that hard to sort out. Basically:

Free market solutions ought to be the presumptive default. Unless there is good reason to the contrary, they ought to be the rule.

1. Exception Number 1: Natural monopolies. It makes no sense to have competition for municipal water supplies; airports; multiple-gauge railroads; fishing grounds; groundwater; or police departments. The basic reason is the putative economic benefit is either simply not there, or is absurdly overwhelmed by the social confusion engendered by multiple suppliers.

In these cases, a form of regulated monopoly is desirable. (By the way, the airline industry at a national level is precisely this kind of market; we do not have too little competition there, but too little regulation).

2. Exception Number 2a: Wallet-driven market power monopolies. It’s strategy 101 in business schools that the way to be successful is to be #1 or #2, and the best way to do that is to get more market share than your competition, so you can drive them out of business. The one guaranteed way to do that is to cut prices so low that no one else can compete. Think Walmart. Think Amazon. Think Japanese in the 60s and 70s in any industry.

The reason we have anti-monopoly laws is to reset the playing field when a competitor dominates the market too strongly.

3. Exception Number 2b: Product-driven market power monopolies. Where the product is so obscure, expensive, infinitely variable, and difficult to understand that the producers are de facto in control, because it is too confusing and too dangerous to challenge them.

Drug prescriptions are an interesting example. The ‘free market solution’ to high drug prices was (partly) to let drug companies advertise, and to loosen up the definition of what constituted a ‘new’ drug. What did we get? New diseases like RLS, new definitions of ‘new’ (moving ‘off label’ to ‘on label’) and even higher drug company profits. Because who’s still going to argue with your doc? Especially when he or she gets side benefits from giving in to the latest DTC ads on network news programs?

Continue reading →