All of the Presidents (except FDR) in this last section were alive and kicking while I was, and so to me they are both more real and less fascinating to some extent. Familiarity breeds, if not contempt, a tendency not to idealize. These leaders are no more flawed than their predecessors, they just seem that way thanks to mass media.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Three terms plus, a World War, a Depression, a transformative Presidency and an epic life spent in public service: FDR is another President who can’t be summed up in an anecdote, one book, or a hundred. He accomplished enough great things to be a deserving icon; he committed enough wrongs to be judged a villain. (He was pretty clearly a sociopath, but a lot of great leaders are, including a fair proportion of ours, including some of the best.) The only completely unfair verdict on this Roosevelt is not to acknowledge the importance and complexity of his life. Here are some of my favorite items about him:

- FDR wrote down a plan when he was still in school outlining the best way for him to become President. The plan was essentially to follow his distant cousin Theodore’s career steps: Harvard, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Governor of New York, Vice-Presidential candidate, and President. (He skipped “Rough Rider.”) Amazingly, he followed it, and it worked.

- Conventional wisdom holds that FDR’s polio transformed his character, and that without that crisis and challenge he would have been content to be a rich dilettante. I doubt it, but there is no question that he fits the Presidential survivor template, and that his ordeal made him stronger, more formidable and more determined.

- Many Presidents had strong mothers, especially, for some reason, many of our Chief Executives from Roosevelt to Obama. Franklin’s mom, however, wins the prize. It’s amazing Eleanor didn’t murder her. But Mrs. Roosevelt is why Eleanor was there in the first place: all of our Presidents raised by strong mothers married very strong wives.

- If a computer program were designed to create the perfect American leader, it would give us FDR. He was the complete package; his charisma, charm and power radiate from recordings and films that are 90 years old. That smile! That chin! That head! That voice! He is one of the very few Presidents who would be just as popular and effective today as the era in which he lived.

- And just as dangerous. FDR is also a template for an American dictator, which, I believe, he would have been perfectly willing to be. It’s no coincidence that Franklin was the only President to break Washington’s wise tradition of leaving office after two terms.

- Political and philosophical arguments aside, at least four of Roosevelt actions as President were horrific, and would sink the reputation of most leaders: 1) Imprisoning Japanese-Americans (and German-Americans, too); 2) Ignoring the plight of European Jews as long as he did, when it should have been clear what was going on; 3) Handing over Eastern Europe to Stalin, and 4) Knowing how sick he was, giving little thought or care to who his running mate was in 1944.

- Balancing all that, indeed outweighing it, is the fact that the United States of America and quite possibly the free world might not exist today if this unique and gifted leader were not on the scene. Three times in our history, the nation’s existence depended on not just good leadership, but extraordinary leadership, and all three times, the leader we needed emerged: Washington, Lincoln, and Franklin. I wouldn’t count on us being that lucky again.

I left the bulk of reflection about the character and leadership style of Theodore Roosevelt to one of Teddy’s own speeches to embody, and I’ll do the same for his protege.

On September 23, 1932, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt gave a speech at Manhattan’s Commonwealth Club. (Everyone, conservative, liberal or moderate, should read it….here.) It was a defining statement of progressive principles and modern liberalism, redefining core American values according to the perceived needs of a changing nation and culture. It is a radical speech, and would be regarded as radical by many today, even after much of what Roosevelt argued was reflected in the policies of the New Deal.

After sketching the origins and progress of the nation to the present, he flatly stated that the Founders’ assumptions no longer applied:

A glance at the situation today only too clearly indicates that equality of opportunity as we have know it no longer exists. Our industrial plant is built; the problem just now is whether under existing conditions it is not overbuilt. Our last frontier has long since been reached, and there is practically no more free land. More than half of our people do not live on the farms or on lands and cannot derive a living by cultivating their own property. There is no safety valve in the form of a Western prairie to which those thrown out of work by the Eastern economic machines can go for a new start. We are not able to invite the immigration from Europe to share our endless plenty. We are now providing a drab living for our own people….

Just as freedom to farm has ceased, so also the opportunity in business has narrowed. It still is true that men can start small enterprises, trusting to native shrewdness and ability to keep abreast of competitors; but area after area has been preempted altogether by the great corporations, and even in the fields which still have no great concerns, the small man starts with a handicap. The unfeeling statistics of the past three decades show that the independent business man is running a losing race. Perhaps he is forced to the wall; perhaps he cannot command credit; perhaps he is “squeezed out,” in Mr. Wilson’s words, by highly organized corporate competitors, as your corner grocery man can tell you.

Recently a careful study was made of the concentration of business in the United States. It showed that our economic life was dominated by some six hundred odd corporations who controlled two-thirds of American industry. Ten million small business men divided the other third. More striking still, it appeared that if the process of concentration goes on at the same rate, at the end of another century we shall have all American industry controlled by a dozen corporations, and run by perhaps a hundred men. Put plainly, we are steering a steady course toward economic oligarchy, if we are not there already.

Clearly, all this calls for a re-appraisal of values.

So Franklin Roosevelt re-appraised them:

…The Declaration of Independence discusses the problem of Government in terms of a contract. Government is a relation of give and take, a contract, perforce, if we would follow the thinking out of which it grew. Under such a contract rulers were accorded power, and the people consented to that power on consideration that they be accorded certain rights. The task of statesmanship has always been the re-definition of these rights in terms of a changing and growing social order. New conditions impose new requirements upon Government and those who conduct Government….

I feel that we are coming to a view through the drift of our legislation and our public thinking in the past quarter century that private economic power is, to enlarge an old phrase, a public trust as well. I hold that continued enjoyment of that power by any individual or group must depend upon the fulfillment of that trust. The men who have reached the summit of American business life know this best; happily, many of these urge the binding quality of this greater social contract.

The terms of that contract are as old as the Republic, and as new as the new economic order.

Every man has a right to life; and this means that he has also a right to make a comfortable living. He may by sloth or crime decline to exercise that right; but it may not be denied him. We have no actual famine or dearth; our industrial and agricultural mechanism can produce enough and to spare. Our Government formal and informal, political and economic, owes to everyone an avenue to possess himself of a portion of that plenty sufficient for his needs, through his own work.

Every man has a right to his own property; which means a right to be assured, to the fullest extent attainable, in the safety of his savings. By no other means can men carry the burdens of those parts of life which, in the nature of things, afford no chance of labor; childhood, sickness, old age. In all thought of property, this right is paramount; all other property rights must yield to it. If, in accord with this principle, we must restrict the operations of the speculator, the manipulator, even the financier, I believe we must accept the restriction as needful, not to hamper individualism but to protect it….

The final term of the high contract was for liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We have learned a great deal of both in the past century. We know that individual liberty and individual happiness mean nothing unless both are ordered in the sense that one man’s meat is not another man’s poison. We know that the old “rights of personal competency,” the right to read, to think, to speak, to choose and live a mode of life, must be respected at all hazards. We know that liberty to do anything which deprives others of those elemental rights is outside the protection of any compact; and that Government in this regard is the maintenance of a balance, within which every individual may have a place if he will take it; in which every individual may find safety if he wishes it; in which every individual may attain such power as his ability permits, consistent with his assuming the accompanying responsibility….

Faith in America, faith in our tradition of personal responsibility, faith in our institutions, faith in ourselves demand that we recognize the new terms of the old social contract. We shall fulfill them, as we fulfilled the obligation of the apparent Utopia which Jefferson imagined for us in 1776, and which Jefferson, Roosevelt and Wilson sought to bring to realization. We must do so, lest a rising tide of misery, engendered by our common failure, engulf us all. But failure is not an American habit; and in the strength of great hope we must all shoulder our common load….

Before “We have nothing to fear but fear itself” and the rest, FDR delivered one of the most influential and important speeches in U.S. history. Like the Commonwealth Speech or hate it, we must concede that Roosevelt’s ideas still drive our public policy debates today.

Harry S Truman

Like many of the Vice Presidents who reached the top of our government organizational chart upon the death of a President, Harry Truman would have never reached the office under normal circumstances. He was short, he was unimpressive physically, he was an indifferent speaker, and neither his career nor his character appeared to show special promise. But like TR and Arthur, and later, Lyndon Johnson, Truman was up to the job, and it’s a good thing he was.

The key to his success was that he was not afraid to make decisions. This is the single most important trait of good leaders. Often any decision is better than a tardy or delayed one, and easily a third of our Presidents lacked Truman’s courage, resolve, and accountability.

The most difficult, controversial and important decision that Truman had to make was his decision to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima. An interesting exercise is to try to discern which of our Presidents would have made the same decision under the same circumstances. Some are easy calls. Both Roosevelts–sure. Ike? Yes. LBJ? Yes. Nixon? Definitely. Reagan? Of course. Probably both Bushes, definitely W. Grant? You bet. Polk? Oh yes. Jackson wouldn’t have just dropped the A bomb, he would have enjoyed it.

Lincoln? I wonder.

The definite no-bomb group would include Jefferson, the Adamses, Buchanan, Taft, Wilson, Hoover…Jimmy Carter would still be considering all the options 40 years later. The most intriguing maybes are Washington, Kennedy and Clinton.

It would make a good parlor game. Back to the real decision: the Truman Library has various records of Truman’s thought process leading up to and after the decision:

-

Secretary of War to Harry S. Truman, July 30, 1945, with Truman’s handwritten note on reverse, regarding the readiness of the atomic bomb and Truman’s approval to release it on Hiroshima. Papers of George M. Elsey. (2 pages)

- Diary entry of Harry S. Truman, July 17, 1945, describing his first meeting with Stalin at Potsdam and expressing optimism in “handling” Stalin, as well as a reference to the atomic bomb. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File. (1 page)

- Diary entry of Harry S. Truman, July 18, 1945, recounting meeting with Stalin and Truman’s intention of telling him about the bomb, as well as mentioning that the Japanese will surrender once Manhattan (the atomic bomb) is released on them. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File. (2 pages)

- Diary entry of Harry S. Truman, July 25, 1945, in which he reflects on the atomic bomb tests and the destructiveness of it, and the plan for using the bomb on military targets only. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File. (2 pages)

- Letter, Harry S. Truman to Bess Wallace Truman, July 31, 1945, describing negotiations among the Allies in Berlin. Papers of Harry S. Truman: Family, Business, and Personal Affairs File. (4 pages)

- Correspondence between Richard Russell and Harry S. Truman, August 7 and 9, 1945, regarding the situation with Japan. Papers of Harry S. Truman: Official File. (5 pages)

- .Correspondence between Samuel M. Cavert and Harry S. Truman, August 9 and 11, 1945, regarding the situation with Japan. Papers of Harry S. Truman: Official File (3 pages)

- Handwritten speech draft, December 15, 1945, detailing Truman’s feelings on his decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan. Papers of Harry S. Truman: President’s Secretary’s File (14 pages)

Truman does not reveal himself as a deep thinker, and this can be an asset with decisions like this. As Ellie (Laura Dern) says to John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) in “Jurassic Park” when everything is falling apart and people are getting eaten, “You can’t think your way through this, John. You have to feel it.” The best leaders have an instinct for what is needed, and do it. Here was Truman’s letter to a critic about the issue 18 years later. It’s not especially persuasive; it’s a jumble of the things that were going through his mind. What matters is that he made the decision, and was able to sleep that night.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

When I was a boy growing up (allegedly) in Boston, there was a popular daytime kids show during the week called “The Small Fry Club” hosted by a man named Bob Emory, who called himself “Big Brother.” A regular feature of the show, which was performed, Howdy Doody-style, before a grandstand of kids, was the Toast to the President. As the camera focused on the portrait of President Eisenhower above and the martial strains of “Hail to the Chief” wafted over the proceedings, Bob, the kids, and all of us at home lifted a glass of milk to Ike. I kid you not.

Eisenhower is one President whose ranking has risen steadily since he left office, as the job he seemed to do so effortlessly has defeated so many of his successors, as more has been learned about his “hidden hand” Presidency, and as the Fifties have become better understood as the perilous minefield of Cold War traps and threats that it was.

Ike shares an oddity with Grant, Wilson and Cleveland: they all switched their middle names with their more common first names (Hiram, David, Thomas and Stephen, respectively) early in life to be more distinctive. Distinctive names are also Presidential: starting with #12, we’ve had no Michaels or Roberts, but a Millard, two Franklins, an Abraham, Ulysses, Rutherford, Chester, Grover, Theodore, Woodrow, Warren, a Lyndon, the formally nicknamed Bill and Jimmy, and Barack. Ike knew what he was doing.

It wasn’t until well after he left office that it became known how often the former Allied Commander was willing to engage in brinksmanship to resolve international crises, threatening nuclear strikes at a time when the U.S. had no real equal in nuclear arsenals. The tally is at least three: against China to end the Korean War, against Russia to get it to back off during the Suez crisis, and China again when Taiwan was threatened. Eisenhower could draw a red line like no other President before or since, thanks to the respect and credibility he had earned during World War II. Nobody thought he was bluffing, and nobody was willing to call his bluff if he was.

Those were the days.

I think I’ll get a glass of milk.

I feel a toast coming on…

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

JFK’s story is made for alternate histories. His father was a bootlegging, Nazi sympathizing scoundrel; the family legacy to its men was misogyny and self-indulgence. Shady deals helped make Jack President, and he was a mass of deception; the truth could have caught up with him in a million ways had he lived. Kennedy had intelligence, wit and ability, but he was also a sick man shot full of enough drugs to confuse a race-horse, a virtual Presidential junkie. His sexual appetite made Harding look ascetic. If one of his affairs, especially the ones with the mob boss’s moll or the Israel double-agent, had become public, he might have been impeached.

At the time of his death, the legacy of Kennedy’s years in office, other than the lies, stood at the space program, the Peace Corps, and a welter of foreign policy blunders that the Kennedy spin machine managed to sufficiently blind the public about so that he escaped the blame he deserved. What kind of President might he have been if he lived, and what would the country have been like as a result? This is Stephen King territory: JFK had the capacity for growth; he also was reckless, ruthless, and arrogant. Any alternate history from an ascendant, peaceful, re-energized world power to a smoldering parking lot is plausible.

I have published this story before. Here is what I think of when I muse about what we don’t know about John Fitzgerald Kennedy:

Several years ago, I had just completed an ethics seminar for the DC Bar. One of the issues I discussed was the lawyer’s ethical duty to protect attorney-client confidences in perpetuity, even after the death of the client. An elderly gentleman approached me, and said he had an important question to ask. He was retired, he said, and teased that I would want to hear his story. I don’t generally give out ethics advice on the fly like this, but I was intrigued.

“My late law partner, long before he began working with me, was Joseph P. Kennedy’s “‘fixer,'” he began, hooking me immediately. “Whenever Jack, Bobby or Teddy got in trouble, legal or otherwise, Joe would pay my partner to ‘take care of it,’ whatever that might entail. Well, my partner died last week, and when I saw him for the last time, he gave me the number of a storage facility, the contract, and the combination to the lock. He said that I should take possession of what was in there, and that I would know what to do.

“Well, I did as he said. What I found were crates and boxes of files, all with labels on them relating to the three Kennedy brothers. There are files with the names of famous actresses on them, and some infamous figures too. There is an amazing amount of stuff, and I have to believe that it is a treasure trove for historians and biographers. I am dying to read it myself. So my question to you is this…

“Jack, Bobby, Ted and old Joe are all dead now, and my partner is dead too. What did my late partner mean when he said I would know what to do?”

And I sighed.

“I would love to know what’s in those files myself.” I said. “But assuming that he meant that you would know the right thing to do and trusted you to do it, your only ethical course is to protect those confidences that Joe Kennedy had been assured would always be between him and his attorney. His surviving family members don’t even have a right to know them, and it’s quite possible, even likely, that Joe wouldn’t want them to know what his boys did that required a “fixer.”

“The only ethical course for you is to destroy those files. Unfortunately.”

“I was afraid you would say that,” he said. “Thank you. That’s exactly what I’ll do.”

And he walked away, shaking his head.

Lyndon Baines Johnson

Lyndon Johnson’s mother changed the spelling of his name from Linden to Lyndon, she wrote, because it would look better on a ballot. Johnson had all the tools to be a great President but not enough of the assets that get Presidents elected. He was wily, smart, gutsy, ruthless when he had to be, a canny negotiator, charmer of both sexes and a natural leader. Unfortunately, he was Lincoln-ugly in a mass media society, and a horrible public speaker. Able as he was, Johnson was never going to be elected President, and then, magically, he was one, the beneficiary of Kennedy’s need to win the Lone Star State (despite his utter disdain for Johnson) and an assassin’s bullet. Suddenly Johnson had power, and he knew how to use it. For the third time (the others: Teddy and Harry), an accidental President had the chops for the big job.

Of course, we now know that LBJ’s story became a Shakespearean tragedy. My next door neighbor in Arlington Massachusetts was Harvard American Government scholar, Professor Robert McCloskey. He was a New Deal liberal, and he loved Johnson. He was convinced that he would be as transformational as FDR. Then the war in Vietnam got ugly; and it derailed LBJ’s administration and McCloskey’s dream.

I remember hearing him shouting in discussions with my father how LBJ was blowing his great opportunity, dissipating his support, tearing the country in two, and he couldn’t understand it. The professor died of cardiac arrest while Johnson was in office. My father believed that his frustration over Johnson and Vietnam killed him.

The problem is that we are all human, and being human in the wrong ways at the wrong time is a constant danger for leaders. Johnson was a Texan to his marrow, and the plight of South Vietnam made him identify it with the Alamo. I wonder if non-Texans understand the deep reverence Texans have for that battle and the heroism of the men there. For Johnson, that identification framed the Southeast Asian fiasco in a way that made it personal, clouded his judgment, and led to a national, cultural and professional catastrophe.

When Johnson died, his body lay in state in the Capitol, and lines wound around the Capitol grounds as citizens, many of them African-Americans, waited for hours to bass by his bier and pay their respects. Was any President so revered and so despised by so many simultaneously?

Richard Nixon

Luck evens out over time. As fortunate as the United States was to have Washington, Lincoln and Roosevelt, great leaders all, at the ready when the nation needed their genius, it was spectacularly unlucky to have two of its most qualified and able leaders doomed to failure because they served in times that exploited their vulnerabilities.

Maybe nothing could save Richard Nixon. He came to office by far the most qualified man ever to become President. He had watched and learned from one of the best, Eisenhower, and also had performed the duties of the office during the multiple occasions Ike was hospitalized or convalescing. Nixon was bright, maybe brilliant; he had Wilson’s knowledge of politics, Lincoln’s tactical acumen and Johnson’s audacity. He was not, however, a great man, and a great leader has to be one. Eisenhower didn’t like him or trust him: Ike’s tepid endorsement of his own Vice-President lost Nixon the 1960 election as much or more than Democratic ballot-stuffing. As usual, Ike was right.

Were it not for Watergate, people a century from now might look at Nixon’s record and wonder, “Why did the news media hate this man? He was more liberal than a lot of Democrats. He did some great things.” Just as there is no explaining charisma and charm, however, it is impossible to understand the stench of insecurity and void of trustworthiness some people carry. Nixon was a lonely, insecure boy who grew to be an almost friendless, paranoid man. All his ability, intelligence and experience couldn’t compensate for the handicap of his hollow character. That is what brought him to ruin. If it had not been Watergate, it would have been something else.

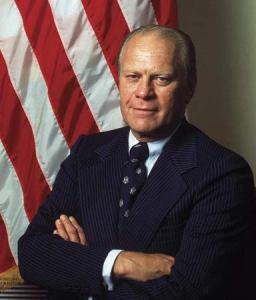

Gerald Ford

My thesis in American Government was on Presidential character, and the first revelation of my research was that these guys, as a group, were weird. They were unusual as children; they knew they were different; they sought power to compensate for other deficits; they saw themselves as being placed on earth for great things. Many felt driven by impossible role models, often their fathers. By the time I completed my thesis, it was clear to me that the typical President of the United States was not psychologically healthy, and was definitely not normal.

Gerald Ford, in contrast, was normal, and was emotionally healthy. He was the only President since Washington who wasn’t elected as Vice President or President, and he never would have been. The recent Saturday Night Live reunion and retrospective reminded me how poor Ford was defined by Chevy Chase’s weekly portrayal of him as a bumbling klutz, the result of several well-publicized accidents on the golf course and exiting Air Force One. It was unfair, for Ford was a well-coordinated ex-athlete. (Nixon, however, was a klutz). Never mind: everyone laughed anyway. Ford apparently laughed himself. But a nice, well-adjusted guy who everyone laughs at can’t lead the most powerful country on Earth. Ford never had a chance.

Jimmy Carter

After the double discouragements of Johnson and Nixon, the United States public decided that it didn’t want a President for a while, so they elected Jimmy Carter. Carter, responding to his mandate, decided to be the anti-President, shedding as many trappings of the office (that is, symbols of power, respect, and the Presidency itself) as he could, appearing on TV in flannel shirts and jeans instead of suits, sounding more like a low-key televangelist than a head of state, and generally guaranteeing that he wouldn’t have the usual presumed legitimacy that the successor to Washington and Lincoln usually can rely on as his sword and shield when the going gets tough. He was sufficiently arrogant (or ignorant of Presidential history and leadership history itself) that he believed that everyone from Washington to Ford had been doing it wrong, and what the people wanted in the White House was a regular old boy like the next door neighbors, who was no better than they were. There were two obvious flaws in this theory. First, people want leaders who are better than they are. Second, Carter was a phony, and it showed. He thought he was smarter than everyone. Still does.

After four years of Jimmy Carter, the public wanted someone who at least acted like a President.

Enter Ronald Reagan.

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan once said that he didn’t understand why people said that he wasn’t qualified to be President because he was “just an actor,” since being an actor was a terrific qualification for a President. Reagan’s acting skills were invaluable, but he had a lot more to offer than that as a leader. However, it is another intriguing “what if?” to imagine what the nation would have experienced if Reagan were not well past his intellectual and physical prime by the time he was elected. The halting, much-parodied delivery than he brought to podiums, cameras and microphones as President gave little hint of the energetic, sharp, intense figure he was more than a decade earlier, when he first came to political prominence. When people saw Ronald Reagan in 1964, making an extended televised speech in support of GOP Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, the reaction was “Wow! This is that washed-up actor from “Death Valley Days”? Watching it today, my reaction is still “Wow.” Whatever one thinks of his philosophy and policies, Reagan was a strong leader who both played the role of President superbly and also knew how to do the job.

Yet what a pity that this guy never had the chance to show what he could do:

George H.W. Bush

I admire Papa Bush as a war hero, and like him as a man, but he was an awful President, one of the worst. He was the third, and hopefully the last, of our “anointed Presidents,” men who never would have been elected on their own merits, but who had their popularity artificially enhanced by an outgoing icon. Van Buren, Jackson’s Chosen One, was the first; Taft, whom Teddy picked to be his stunt Roosevelt, was the second, and Bush, Reagan’s Designated President, was the third. All were unsuited for the job and failed, but none more so than Bush.

Aspiring to be President because you’ve been everything else is a lousy reason to run. Bush had an incredible resume but no leadership ability or mission: when he had, briefly, a 90% approval rating in the wake of the first Iraq War, the equivalent of a Presidential “DO WHATEVER YOU THINK IS IMPORTANT” coupon, he chose…nothing. Inexcusable. Imagine almost any other President other than Pierce lying drunk on the floor, and imagine what they would do with such a gift.

I’m through with Bush. It makes me furious just thinking about him.

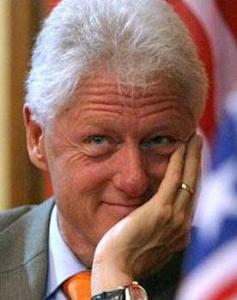

Bill Clinton

Clinton is the Democratic Nixon, and not just because he almost got himself thrown out of office. When those people a century from now look at his record, they’ll ask, “Wait, this guy was a Democrat? Why did conservatives hate him so much?”

Well, he had to work at it. Unlike Bush 1, Clinton had all the moves. He was a natural leader, smart, and ambitious. Unlike Nixon, he oozed charm, as so many sociopaths do. (My father, who hated Clinton, met him once late in his eighties, and was disturbed by the experience. “He is the most likable person I have ever met in my life,” he told me. “It’s scary.”) Bill Clinton could have been a great unifying force in our politics and culture, and might have helped us avoid the toxic polarization that threatens the nation’s comity and stability today. Instead, he exacerbated divisions, and corrupted both the political culture and the culture itself.

Again, luck had a hand in this result. Bill Clinton would have been a great crisis President. He just never had the crisis to show what he could do. He got bored. And when he was bored…well, you know.

George W. Bush

I hate to end this parade with a whimper, but I don’t have much to say about the George at the end of it. He had more leadership instincts and skills than his father (but who doesn’t?). When W had public support, he tried to use it, first for social security reform (and was foiled by entitlement-loving Democrats) and after his re-election, for immigration reform, which was shot down, foolishly, by his own party. Much of his Presidency was controlled by moral luck, beginning with the 2000 Florida recount. Whether WMD’s were found in Iraq was pure moral luck: how different views on the war and Bush’s Presidency would be if Saddam had the weapons he pretended to have.

In one respect, George W. Bush is the perfect President on which to leave this survey, because in his post-Presidency, he has, perhaps more than any President since Hoover, embraced the mission of the long, four-part salute. He is a man who communicates to us that he is proud to have served, did the best he could in a difficult job, isn’t bitter toward his critics, understands what his successor faces, and will abide by the verdict of history.

So thank you all, from George to George, and our current President too. We owe all of you a lot, even though we sometimes don’t act like it. As Teddy said, you were and are among those

“whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat…”

Hail to the Chiefs.

***

Don’t want to mention Obama our current POTUS? I think I understand your decision to omit him. Going back to FDR, I think he was a great wartime leader for awhile. He did not end The Great Depression. Amity Shalaes in *The Forgotten Man* explains in great detail exactly why. As far as Eisenhower considering the potential danger of nuclear holocaust, he was definitely the right man for the job. Clinton and Nixon do have some things in common although it is almost impossible for me to think of Nixon as a womanizer. I was taught that Generals did not make good presidents. I think lawvers, with the exception of Lincoln should stay in Congress.

I didn’t say that FDR ended the Depression. The war ended the Depression. FDR’s genius was getting the country through the depression by doing things, being inspirational, leading. That was his contribution and his genius.

I think I noted that Obama isn’t included in the original introduction: Presidents Day isn’t to honor sitting Presidents. In America, we don’t celebrate birthdays of living figures, or treat Presidents as kings.

I’d say he called it. Not so much in the USA – though that’s bad enough – but worldwide. The richest 300 people have more wealth than the poorest 3,000,000,000.

Odd that FDR would negatively speak of such a prophecy as his policies did more than anything to ensure that trajectory.

I too found Truman’s viewing the bomb as revenge for the kids killed at Pearl Harbor astounding.

I don’t. I see it as logical consequences.

I don’t read revenge at all in his letter. The opening and closing are both solid wartime utilitarianism. The middle bit an emphasis that the dirty and ugly deed that must be done would not have been necessary if not for Japanese treachery.

That is how I read it too, Tex.

That’s a misreading of history. Washington never set up any such tradition; he couldn’t have, as it would have taken several presidents in a row to do that. In fact, the first tradition that did develop, once matters settled out, was for presidents only to serve for one term; Trollope remarks on it, in his North America, written about the middle of the U.S. Civil War (and so, before Lincoln ran again). It was Lincoln who broke that convention, which was a factor in arousing suspicion of his dictatorial ambitions among those who conspired against him. The two term tradition only developed after Lincoln.

What makes you think that? Choosing a poor fall back is a well known ploy to reduce the risks of being squeezed out, in this case by pressure to resign for reasons of health. Think poison pill.

The logical fallacy here is a hidden variant of the “Texas sharpshooter fallacy”. Had different leaders been there with different values and achievements, you would be a product of those and would be using what you accordingly lived in as a measure of success. For instance, had Lincoln failed all today’s U.S. patriots in the southern states would be hailing Jefferson Davis’s success in liberating them from the U.S.A.

Good contrarian arguments all. Still tortured and wrong, however.

1. Washington, as the first of his kind, knew that everything he did would set the standard for Presidents to come. He decided that he should be called “Mr. President,” for example. I suppose that standard wasn’t officially set until John Adams followed it.

Teddy Roosevelt, announcing (foolishly) after his his election in 2004 that he would follow Washington’s tradition, was a President and a historian…I trust his assessment of the situation, but you are welcome to your bizarre interpretation. Jefferson, Monroe and Jackson served two terms before Lincoln and then refused to run again; Adams, John Quincy Adams and Van Buren attempted to have second terms, and those who didn’t run, except Polk, who wasn’t well, were simply unpopular with their parties and the public. Your one term theory never “shaked out”—on this you’re just factually at sea. Lincoln, amusingly, was one President who couldn’t influence the tradition at all, since he was dead and never had the chance to choose to run for a third term. The first elected President after Lincoln, U.S. Grant, actually tried to mount a campaign for a third term, and was discouraged in part because the effort was widely derided as unseemly as a breach of the tradition that Lincoln set,requiring a President to be shot after his second term. KIDDING! The tradition was attributed to Washington. Your theory doesn’t hold any water at all.

2. Why do I think that? I think it because FDR was given a choice of three VP candidates to run with, one of which he barely knew—Truman—and told the party that any of them would be fine. And he was very sick. The chances of Roosevelt being impeached during a war (or ever, given his popularity), was 0.00, and he knew it.

3. It’s not the Texas sharpshooter at all. The nation had three existential crises, and three near-perfect leaders to deal with them. It’s not a manufactured cluster, it’s a clearly delineated and exclusive group.

https://ethicsalarms.com/2015/02/18/a-presidents-day-celebration-part-4-and-final-the-wild-wild-ride-from-fdr-to-w/comment-page-1/#comment-312998

But hey, if a british novel writer from the 1800s wants to say otherwise…who are we to argue.

Yes, this was not one of PM’s stronger efforts, but he gets points for valor.

By the way, if anyone is curious, that is an implied ad hominem or well poisoning directed at Trollope.

(But a valid argument directed at his acolyte, pm Lawrence)

But a really good one.

And,on the second point, FDR knew he was seriously ill when he ran for the fourth term. He allowed the American people to be deceived by a false medical report that he was the picture of health. The Democratic National Convention understood that his running mate would very likely be his successor sooner rather than later. That he would put so little consideration into his choice of Vice-President while the country was in the middle of a war was short-sighted, vain and dangerous. He barely knew Truman. What if Harry hadn’t been up to the challenge…as so many assumed early on?

The fact that FDR was wildly irresponsible in this instance isn’t seriously disputed, even by FDR’s biggest fans.

“[FDR] allowed the American people to be deceived by a false medical report that he was the picture of health.”

The likelihood of that being repeated in regards to 45th President Hillary alarms me as much as the impending ethics disaster of Hillary herself.

Kennedy also hid his health problems (Addison’s Disease, crippling back pain, and quite possibly PTSD) from the country. I don’t know what’s worse, lying about your health or lying about your goals, a la Obama.

I do think that FDR’s polio affected him in terms of how he was viewed by others. FDR, for many reasons, hadn’t been well-liked in school. His mother’s indulgence certainly was a major cause of that. But not entirely.

“The Roosevelts” documentary discussed how FDR would whiff his head up with that stereotypical rich person nose-in-the-air gesture when greeting a fellow classmate. His height and aristocratic bearing, along with a certain amount of arrogance projected him as a standoffish person. And others picked up on that.

The wheelchair no longer allowed him to physically look down on people and, to some extent, didn’t give others the idea that he was figuratively looking down on them either. Not only did it give people a more favorable impression of him, but it did give him a certain amount of empathy for suffering people that I’m sure he really had before. His Warm Springs treatment center for polio sufferers never would have existed if Roosevelt hadn’t had first-hand experience and those who went there for treatment remember him as a far-more relaxed and amiable person than his contemporaries in Washington, DC.

Yes, excellent analysis.

My friend who I mentioned in Part 3 STILL thinks Carter is “the most wonderful man who ever lived in the White House,” and that America neither appreciated his efforts toward peace and the alleviation of suffering then, nor appreciates them now. When I pointed out to him that Carter’s freelance diplomacy in the run-up to the First Gulf War was inappropriate and probably illegal under the Logan Act, which specifically disallows private individuals from conducting their own foreign policy, his response was “That’s Jimmy Carter, conspirator and manipulator extraordinaire, that’s why he got the Nobel Peace Prize and spends all his free time building homes for the homeless.” I changed the subject then to avoid damaging the friendship, which ended when I couldn’t deal with his constant liberal posting on social media, but I have prepared an essay meticulously setting forth all of Carter’s incompetence and wrong acts in and out of the Presidency, with what I hope is the right amount of barbed humor, since I don’t want to be accused of too many cheap sneers and jeers, and I will launch it over social media the moment his death is announced.

3) especially arguing hypotheticals is irrelevant in this case. The assertion- when America needed leaders, those good ones emerged. Saying “well if bad ones had emerged we’d be singing my a different tune” is irrelevant because it does nothing but bolster the assertion that when America needed the leaders THEY emerged and not bad leaders.

Jack, just want to thank you for an amazingly informative and entertaining series. I was born during Truman’s term, so I remember none of it. However, from Ike on I have very clear memories of the rest, and I think your analysis is spot on. Historically, what I know of the rest, I pretty much agree with.

Thanks. That means a lot It was a lot of work (more than I expected) but of course still a labor of love, because it’s true: I really do love these guys, the institution, and all these amazing characters and stories. I hope everyone enjoys it as much as you and me.

Your posts on the presidents are worth combining into an article for a national magazine. I appreciate all your work and thoughtful treatment of each man – among the most thought-provoking reading I have seen in your blog. It all makes me get real serious about thinking about whatever I will leave behind to be said about myself.

By the by—my favorite Presidents (not necessarily the “best”):

Washington, Jackson, Polk, Lincoln, Arthur, Cleveland, Teddy, and Ike. Yes, it depresses me that nobody’s been added to the list since 1960.3 Republicans, 3 Democrats, and a Federalist.

My least favorites: Pierce, Buchanan, Wilson, FDR, Nixon, Bush 1, Clinton, and Obama.

This is probably apocryphal, because I don’t remember the news conference, but the story is told that during the Berlin Airlift, Ike was asked by a reporter at a news conference “Do you rule out the use of nuclear weapons to resolve this crisis?” Ike responded “No” and moved on to the next question.

Sounds plausible to me.

Ask him a question and he would give you a straight answer, not a politically correct one.

Whether or not it actually happened, it’s a hell of a good story.

Ford…definitely not a klutz. Kept his cool after two assassination attempts in just one month. I never liked Chevy Chase.

Ford’s words soon following his inauguration (not sure if it was his first speech as POTUS) still ring in my ears as if I am actually hearing them in the air. I can’t quote him, but he said something like: “Hey, I know I wasn’t voted into this office. But, that being the case, I don’t owe anything to anyone but my wife.” As rough as that sounded, I liked him right away for that. He did some things I did not like (my memory gets fuzzy here), but I definitely had more confidence in him than I had in Carter when the ’76 election came up. I was younger, and still stinging from Nixon’s follies; Carter of course seemed like the “cleaner” choice.

The mentions of the president’s wives make me want to see as thoughtful an analysis of their lives and influence. They are a diverse and interesting group as well. It’s revealing to see how these men related to their wives as well.

There are one or two good histories. Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Dolly Madison, Rachel Jackson…Mrs. Taft, who made her husband accept TR’s offer of the Presidency rather than a Supreme Court appointment, which is what Taft wanted, Edith Wilson, Mrs. Harding, Eleanor, Jackie, Lady Bird, Pat Nixon, Betty Ford, Rosalind Carter, Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush, Hillary, Laura, and Michelle Obama were all extremely strong, smart, women and influential on their husbands.

Too tough on George the Elder and too kind to Bill Clinton!

Thank you for a wonderful series, I’ve just finished it, I was a bit busy in February. I thoroughly enjoyed it.