I know this is a long essay.

Yes, it involves baseball.

Bear with me. I think it is worth your time.

Last night, in Game 1 of the 2013 World Series, embarrassingly kicked away by the St. Louis Cardinals and won handily by some team called the Boston Red Sox, an intricate ethics drama appeared, allowing us to see the painful process whereby a culture’s ethical standards evolve and change in response to accumulated wisdom, altered attitudes and changing conditions. An obviously mistaken umpire’s call was reversed by the other umpires on the field as the Cardinals manager argued not that the original call had been correct, but that reversing it was a violation of tradition, established practice and precedent….in other words, doing so was wrong, unfair, unethical because “We’ve never done it this way,” a variation of the Golden Rationalization, “Everybody does it.” You should not have to appreciate baseball (but if you don’t, what’s the matter with you?) to find the process illuminating and thought-provoking.

First, some historical background. Organized baseball has been around since the mid-19th Century, and umpires have always had a crucial and perilous role in making it function. Well into the 20th Century, they were in physical peril from players, managers and fans, who would sometimes try to exact violent revenge for game-altering decisions, right and wrong, in the game and after it. All referees in all sports have to make difficult judgment calls, but none have as many to make as umpires. Every pitch to a batter that is allowed to go over the plate without a swing requires an umpire’s call. The strike zone varies with height and “natural batting stance” of each batter, and there is no position where the umpire can stand that permits equal accuracy of measurement from all angles. If the umpire is standing straight up to see over the catcher’s head, he cannot quite determine how low a pitch is. If he crouches low, he must peek around one side of the catcher or the other; if he chooses one side, he has to guess at whether a pitch to the opposite side has crossed the plate.

On plays in the field, the problem is even worse. An umpire often has no idea how a fielding play will develop, and must guess at the best place to stand where the ball, the fielder’s glove, the base and the baserunner can all be seen clearly at the crucial moment when the runner is either “safe” or “out.” Sometimes there is no ideal spot. Sometimes a player blocks the umpire’s view; sometimes a player intentionally blocks the umpire’s view. There are also plays, including the safe or out call on a ball thrown to first base after a batter’s struck ball has been fielded by an infielder, the most common play in the game, where the umpire must be watching two locations simultaneously that frequently are too far apart to be seen simultaneously—the ball reaching the first baseman’s mitt, and the runner’s foot touching first base. On this play and others, spectators in the stands, as well as some players on the field and those in the dugouts, often have a better view of the play than the umpires who have to call it…or not. The umpires, at least theoretically, are neutral. Players,coaches, managers, spectators and broadcasters aren’t; they see what they want to see, as confirmation bias often overwhelms the senses.

Baseball’s reasonable and unavoidable solution to the inherent vulnerability of the umpires, and thus the game itself, to constant arguments over what really happened, often a Rashomon problem with no objective answer that can ever be settled definitively, was this: what the umpire decides is reality, is reality. The decisions are final, and are not reversed. Players and managers can argue until they are purple, there can be photographs and sworn statements to the contrary, it doesn’t matter. Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem reputedly answered a baserunner who heard no call from the ump for many seconds after a close play at third base and asked, “Well, ump, am I safe or out?” by replying imperiously, “You ain’t nothin’ until I say you are!”

Many things naturally flowed from the institutionalized position that the umpire was always right. It meant that an umpire would never reverse his own call, even when, as occasionally happened (and happens), an umpire reflexively gave the wrong signal and knew he was wrong immediately. Since showing fallibility would undermine the stability of the game itself, the umpire would never admit the botch. (“I’m sorry, did I say strike? I meant ball. My bad.”) Similarly, an umpire’s code evolved: even if the other three umpires clearly saw that their colleague’s call was obviously, ridiculously incorrect, they would never intervene or overturn him as a matter of professional courtesy and loyalty. The exception was a rulebook interpretation. Baseball has strict, complicated and voluminous rules, and those have to be obeyed. If an umpire’s bad call is based on a misreading of a black-and-white rule, the umpiring crew will overturn it.

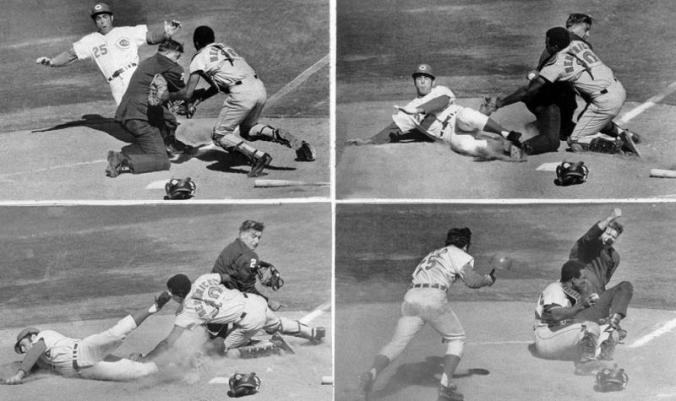

This utilitarian resolution of a structural problem made practical and ethical sense, as long as there was no definitive record of blown calls after the fact. Gradually, the increase in televised games, the advances in high-speed photography and the improvements in technology made the old solution increasingly unsatisfactory, and no longer ethically defensible. In the 1970 World Series, for example, the evidence that this crucial play was called wrongly became undeniable once the photographs of the sequence were published:

Reds runner Bernie Carbo is called out by the home plate umpire, who can’t clearly see the play, despite the fact that Orioles catcher Elrod Hendricks tagged Carbo with his glove while the ball was in his other hand. These kinds of blatantly mis-called plays had happened before, of course, many times, but they were increasingly damaging to the sport as baseball became a bigger business and was more widely seen and followed. The outcome of games meant millions of dollars to cities, franchises, merchandizers and players; without integrity, baseball’s credibility and popularity were at risk.

The evidence of crucial blown calls kept proliferating, both during the regular seasons and in the play-offs and World Series, where they were especially well-publicized and embarrassing. An umpire blew a critical and blatant interference call in Game #3 of the 1975 World Series that may have changed the outcome of that famously close battle; an even worse call at first base did alter the result of the 1985 Series, literally robbing the St. Louis Cardinals of a decisive game victory. As it always had, Major League Baseball moved at a glacial pace, and the old ways remained unchanged, though steadily under attack. The umpire’s union even got MLB to ban the showing of video replays in ballparks that had the new giant video screens on their scoreboards when an umpire had blown a call and the replay would prove it. But as so often happens, technology was relentlessly undermining what was increasingly seeming like a cover-up. Fans, broadcasters, managers, team owner and journalists were no longer content to accept it when games and championships were decided by mistaken umpire decisions.

The tipping point may have come in 2010, when a fine American League umpire named Jim Joyce robbed Detroit pitcher Armando Galarraga of one of the most celebrated of baseball achievements, a no hit, no base on balls perfect game, by blowing the very last play of the game on national television. The umpire courageously admitted his error afterward, but the damage could not be undone. What should have been a highlight of a young pitcher’s career and the 2010 season as well as a great historic moment for Tigers and the game itself became, instead, an ugly blot. Although no formal system is yet in place that would prevent another Joyce-Gallaraga incident, the culture of umpiring, undoubtedly with the assistance of pressure from MLB, began to change. The important thing, we began to hear, was “getting it right”…and “getting it right” is a good description of ethics itself.

Increasingly, fans heard umpires emulate Joyce by admitting mistakes after games. More and more frequently, umpires gathered to discuss controversial calls, and occasionally reversed them. In 2011, MLB installed the first video review system, to be used only on the notoriously difficult fair-foul calls on batted balls and disputed homeruns decided according to the often baroque and confusing structural oddities and ground rules of the various ball parks and stadiums. This year, baseball announced that it would be installing some kind of broader in-game video review system that would presumably prevent incidents like the perfect game fiasco.

This is called progress. If winning and losing games according to what really happened rather than according to a mistaken but authoritative version of what happened is fair and just, it is also ethical progress….which brings us to last night’s moment of truth:

In this play, an attempted double play on a ball hit by Boston’s David Ortiz in the first inning, Cardinals shortstop Pete Kozma never had the ball in his glove, meaning that the runner, Dustin Pedroia, was safe. Umpire Dana DeMuth, who was right in front of the play, inexplicably ruled otherwise, that the fielder had gloved the ball, and only dropped it while transferring it to his throwing hand for the relay to first. Everyone else—literally everyone—could see this was wrong, and most importantly, video replays would show it was wrong forever, if the ruling stood. Since the context of the play could have well changed the outcome of the game, the umpires, after a vociferous protest by Red Sox manager John Farrell, went into a conference on the field and reversed the call.

Then Cardinals manager Mike Matheny argued equally vociferously against the reversal, though he also saw the play, and even confirmation bias couldn’t have caused him to miss the fact that his player flat out missed the ball. What was he arguing? He explained in the post game press conference:

“That’s not a play I’ve ever seen before. And I’m pretty sure there were six umpires on the field that had never seen that play before either. It’s a pretty tough time to debut that overruled call in the World Series. Now, I get that trying to get the right call. I get that. Tough one to swallow.”

Translation: “This isn’t how past mistakes by umpires have been handled, and those of us who play the game have a right to know what the system is. The first game of the World Series is no time to change the system without notice. I don’t care that the umpires got the play right. It’s unfair to violate established precedent. My team, the Cardinals, was robbed of a World Series championship in 1985 when everyone saw the umpire blow a call that cost us Game Six. You guys didn’t overturn that horrible call. When did the system change? I missed that memo!” Up in the Fox broadcast booth, color man Tim McCarver, like Matheny a former player (and Cardinals catcher), was saying the same thing. And the translation of the translation is really this:

“It’s unethical to do the right thing in this situation, because we’ve always done the wrong thing before, and there were good reasons why.”

This is not as absurd or unreasonable a position as it appears. Process is an ethical value. Participants in any system should be able to rely on a consistent process that does not change arbitrarily. The opposing position is that when the process results in an injustice, it is wrong to insist on the integrity of that process: “get it right!” Does this dispute sound familiar? This is the 2000 Presidential election Florida recount case, in baseball terms.

That controversy was and is tougher, because there was no definitive videotape to show what “the truth” was: what the “correct” vote count in Florida was then and is now impossible to determine. In both cases, however, a variation from the established process was employed to try to “get it right” at a moment when simply accepting an error as “part of the game” was deemed unacceptable, unjust, and wrong.

There are other ethical issues here as well, as lawyer-NBC baseball blogger Craig Calcaterra points out in his post about the incident:

- “How often could other umps overrule their colleagues because they saw the play better? I suspect a lot.

- “How many blown calls are known to be blown by the other umpires but are never overturned because either the manager doesn’t come out to argue like Farrell did or because it’s not as big a situation as that one was on as big a stage as the World Series? Again, I suspect a lot.

- “If umpires are able to confer…as quickly as they did to get the call right…why does Major League Baseball lack confidence in a replay system driven by the umpires — say, a 5th one in the booth — and want a managerial challenge system so badly?

“I suspect that last bullet point is explained by the first couple of bullet points. Baseball worries about umpire ego and knows that, absent Farrell coming out to argue, they’re not going to convene and overturn their buddy out of some dumb code of umpire solidarity. As such, they want to make them do so (via video anyway) upon a manager’s challenge.”

So umpires are still struggling to lose the traditional attitude that their calls should not be challenged by colleagues. Managers and players feel that they should know what the process is, and that “getting it right” isn’t an excuse to change the system mid-game. For their part, fans just want the deserving team to win the game. Such a seemingly simple objective, yet it after 150 years, baseball isn’t quite there yet.

The same can be said of human civilization. It’s not there either, and the journey is often traumatic.

________________________________

Sources: NBC Sports 1, 2

Graphic: Bleacher Report

First, to be fair you’re putting words in the managers mouth. But putting that aside for the time being I think this goes a little deeper than you think.

From my understanding of the call in this game it goes against all established and written rules. I would assert that it is unethical to change established and written rules by 1. FIAT and 2. in the MIDDLE OF A GAME, regardless of whether or not the change was “fair”. To do so undermines the system itself and respect for established law. An example of this effect can be seen in the political arena, where doing what’s “right” by the current holder of the executive office seemingly trumps all established precedents on the balance of powers.

Basically this is a “letter of the law” versus “spirit of the law” issue. I believe the tertium quid to exist in the following course of action: If the rule is wrong–change the rule BEFORE the game, print it in the rulebook, don’t change the rules in the middle of a contest because you feel like it.

Basically you’re standing for the proposition that umpires can change rules in the course of a game. Now, that is unfair the reasons behind such an action are altogether irrelevant.

Whoops…this is what happens when you make assumptions about where someone is going. I see we say basically the same thing in the end. Apologies.

Maybe I’m just a horrible person, butwhen I read “botched DP”, my mind went to a very different place…

Now that’s funny right there, I don’t care who you are…

answer to your “what are rights question” that probably won’t show up in your notifications.

Were you surprised when Ethics Alarms showed up at the top of the list from your usual search string?

“Now that’s funny right there, I don’t care who you are…”

God, I hate it when I don’t get it.

I need and desire to laugh more, even if I cannot possibly get out more.

WOULD SOMEBODY PLEASE EXPLAIN FOR ME?????!!!

Yeah, someone else can explain…

Thanks – I figured it out. But not because I was thinking again about whether your nom-du-blog has some connection to a…starts with p (or c) (but not the same p as the “DP” the wisecrack was about, just a, sometimes, related p).

You’re not a horrible person. But depending on how someone acts when there is a “botched DP,” that someone could easily be a horrible person.

botched DP is just the crap that Mr. Pibb is.

I can’t say for sure what he meant but I can tell you what I thought of at first.

Botched DP = botched death penalty.

Example: The Convicted is strapped into the electric chair (for dramatic purpose, let us say that it was Pennsylvania’s “Old Sparky”), everything is in place, silence falls on the crowd… then…the first jolt is delivered, but oh, no, it did not reach the appropriate voltage and rather than being rendered brain dead our criminal is simply being fried, alive, and… as an acrid stench rises… molten flesh drips from under the leather mask…

Or to put it another way, perhaps the fall on the rope wasn’t long enough.

Was that scary enough, Eeyoure ?

Thanks Finlay, that is horrifying, but what the gentlemen are discussing is, er, let’s just say something besides inside baseball.

But I do still support the death penalty – including by hanging – but not by electrocution, mainly because, well, why waste all that energy, when there’s plenty available for free because of gravity?

Yeah…

It wasn’t that…

Completely understandable…

I got it. God Bless Google. God Bless victims of botched DPs – even if no baseballs, gloves, hands, feet, bats or other accessories are involved.

Lack of brain injury…

So the White House can make the excruciating, extraordinarily high-impact decision to sack a low-level, temporary staffer who called a senior staffer a derogatory name, but will not even state a name to account for the failures of the rollout of the health care website. Got it.

Obviously, the White House “best practice” is: “It’s unethical to do the right thing in this situation, because only we decide when the right thing is the wrong thing, and vice-versa.”

Jack, Very well done. It may not get much attention but you did a great job on this one.

Thanks. And no, almost nobody reads the baseball posts—thank you also for doing so– and my planned book about how baseball can be a terrific teaching tool in life and ethics will never find a publisher. Such, as my father would say, are the vicissitudes of life!

Write the book and put it on amazon as an e-book for $1.99…

Thanks. And no, almost nobody reads the baseball posts—

***********

I try to, I really do, but about halfway through, my eyes glaze over.

If only there was something exciting about the game.

Haha

Not to accuse you or scold you, Finlay, but I suspect you suffer the Curse of the Non-Player (of baseball that is). That curse is usually cured if one actually plays the game and enjoys it, while learning of all its possibilities. But I don’t know if you have ever played, so I might be acting unfairly toward you.

I always read the baseball posts! You should make them required. If you are serious about doing a book, I recommend you check out “The Cheaters Guide to Baseball” which is a delightfully amoral examination of the history and methods of, well, cheating at baseball.

I hear many fans who don’t want replay in baseball (and don’t like replay in other sports) because… “tradition”. So not all fans want the “deservinig team” to win if it means changing that tradition.

I feel the game is only improved as technology allows for the review of blown calls. Of course, as an Orioles fan, blown calls can still be painful. Jeffrey Maier… grrrr.

Exactly. That was on my list too, though I’m not sure that the other umpires knew that call had been blown.

in a way I support the tradition because of the way it forced a lesson in good sportsmanship, when the umpires make an unfair call the proper response is to continue the game and get over it. This instance is more confusing because Farrell/the Red Sox weren’t complaining about the obviously bad ruling, in fact he argued for the bad ruling to stand, but the umpires decided on thier own to change the ruling. The umpires and not the coaches/players/fans calling for the review is a different type of instant-replay than is common in sports, and somehow I get the impression that it is more sportsmanlike.

It may be instructive to consider – and compare and contrast – the origins of the British phrase “it’s just not cricket”, which hark back to a time when that game’s standards were ethically higher than they are now, whatever the actual practice.

I was going to leave a slightly sarcastic comment about how I don’t give a crap about baseball because I find baseball utterly, tooth-grindingly, tear-inducingly boring.

But then I remembered a car ride where my father went into a grocery store to get something and I sat and listened to the local sports guys talking about them trying to institute the instant replays. One of them was saying, “You gotta get it right!” The other guy was saying, “I agree, but baseball takes too long as it is!”

My biggest gripe about baseball is it takes the same length of time as about three short movies. It just takes too damn long. The second guy was suggesting that the game needs to get ratcheted down so plays take less time and they don’t stand there thinking about the pitch all week. He didn’t deny that getting it right was important, but if it makes the game take even LONGER, and it makes even LESS people watch, it’s almost counterintuitive.

As it is, I’m all in favor of anything that makes who the winner is in any game clearer, and if a pitch-clock or whatever else can speed up the game is necessary to make the time so the winner will prevail more often, that should be done. I might actually watch.

Well, probably not.

The time issue in baseball in unsolvable, because so much of it is locked into universal TV coverage. An average baseball game took 2.5 hours, give or take, from the i9th Century well into the 70’s (and people without the patience to follow it called it boring then, too.) Now a game averages 3 hours or more. Now TV requires at least 3 minutes of ads during inning breaks and between innings—do the math. Changing the teams over into the field used to take 90 seconds. Add another 90 seconds for more commercials, and that’s an additional 24 minutes of dead time. At the park, there is always plenty to watch and do in those spaces, so few complain. But it drags the game out.

The rest of the time is simply how the game is now played, thanks to more sophisticated strategy. Tony LaRussa singlehandely added an extra 5-10 minutes to games by popularizing single-batter pitching match-ups. Sensitivity to pitch counts and the realizations that On base percentage was a key feature of offense led to the new Boston Red Sox style batting technique, where batters risk strikeouts to “work the count,” tire the pitcher and take walks. There are more pitches per batter now. You could save a little time with a pitch clock, but baseball is not a clock game—it’s not going to happen.

All that said, complaining about the length of a good baseball game (they aren’t all good) is exactly like complaining that a great novel, play or movie is “too long,’ or that a Mozart concerto has “too many notes.”

Except for the fact that those other things you named are entertaining.