A recent article on the web that purported to explore the ethics of “scent branding” was fascinating for two reasons.

First, “scent branding” is a term I had never encountered before, for a practice that I had not focused on. About five seconds of thought, however, made me realize that indeed I was aware of the phenomenon, and had been for quite a while. “Scent branding”—using fragrances in a commercial environment to create a desired atmosphere and to prompt positive feelings, recollections and emotions from patrons—has been around a long, long time, though not under that label. When funeral parlors made sure that their premises smelled of flowers rather than formaldehyde, that was a form of scent branding. Progress in the science of scent allowed other businesses to get into the act: I was first conscious of the intentional use of smell when I spent a vacation at the Walt Disney World Polynesian Villages Resort. The lobby and the rooms had a powerful “tropical paradise” scent, a mixture of beach smells, torches and exotic fauna. It was obviously fake, like much in Disney World; also like much in Disney World, I found it effective, pleasant, and fun. I certainly didn’t think of it as unethical. I was normal in those days, however.

Well, more normal.

The second aspect of the article, entitled “Is it Ethical to Scent Brand Public Places?”, that caught my attention was that it had an obvious agenda. The piece was opposed to scent branding, and set out to find the practice unethical in order to justify condemning it. I see this a lot, and it is an increasingly popular practice with activists whose definition of “unethical” is “I don’t like it.” Obviously not liking something, legitimately or not, creates a strong bias to find that something is objectively wrong with it. That is good cause to check one’s ethics alarms, because unfairness and dishonesty is lurking. I wrestle with this problem daily on the blog, and undoubtedly without complete success. The article on scent branding, however, made no effort to be fair or to use objective analysis.

At least the author didn’t pretend otherwise. Here is how the essay’s author, Siobhan O’Connor, describes “scent branding”:

“Scent branding, wherein hotel chains, electronics companies, or lingerie lines create a signature smell and then stink-bomb the hell out of their lobbies and shops—is becoming quite the thing.”

Gee…I can’t wait to find out whether she thinks this is a good thing or not.

Here is a more nuanced description of the practice, from a fascinating article in Bloomberg Businessweek last month:

“…Jovanovic and Gaurin, who are responsible for luxury colognes and perfumes such as Tom Ford Black Violet and Giorgio Armani Onde Extase, are leading the latest fragrance business craze, a form of sensory branding known as “ambient scenting.” Jovanovic, 34, helped pioneer the trend by creating the “woody” aroma—a combination of orange, fir resin, and Brazilian rosewood, among others—for Abercrombie & Fitch. Since its roll-out in stores across the country two years ago, Abercrombie’s Fierce, which also pervades sidewalks outside the clothier’s stores, has become an integral part of the shopping experience. Popular demand compelled the company to produce the trademark odeur in bottle form, and, according to Jovanovic, customers have complained when store-bought T-shirts lose the smell after multiple washes.

Scenting an entire building is the latest ambition in a growing business that has, for years, gone unnoticed by most consumers. Roger Bensinger, executive vice-president for scent marketing company Prolitec, estimates there are now 20 companies worldwide specializing in ambient scent-marketing and dispersion technology …research showed that not only did customers under the subtle influence of his creation spend an average of 20 to 30 percent more time mingling among the electronics, but they also identified the scent—and by extension, the brand—with characteristics such as innovation and excellence….”

Hmmmm. Tell me more:

“…Advances in scent harvesting and dispersal technology, or the ability to deconstruct scent compounds and recreate them, means perfumers can now produce virtually any scent. As documented in Martin Lindstrom’s book Brand Sense, a Rolls-Royce investigation into customer complaints that the luxury cars had lost their feeling of excellence fingered scent as the culprit. The automaker responded with “a chemical blueprint” for the smell of the 1965 Silver Cloud. …The smell is now applied beneath the seats of each car as it comes off the line. As of 2003, Cadillac began processing scent into the leather of its seats. They called it Nuance….

“…In April, Parsons New School for Design in New York hosted a conference to honor the launch of an transdisciplinary master’s program that includes olfaction. As part of a “Scent as Design” seminar, organizers enlisted luminaries from various fields to collaborate with fragrance experts. Among the first explorations is furniture: a butcher block that suggests the meaty whiff of being inside a butcher shop. Another is the South Bronx housing project imbued with the scent of happiness.

“While the residents of [the housing project] appear to be guinea pigs for an emerging industry, Carter sees ambient scenting as a “no-brainer,” a practical tool to be used in the national effort to re-green America’s inner cities. Jovanovic may have said it best while spritzing L’Eau Vert du Bronx du Sur in a communal bathroom: “It’s impact on behavior on a social level!”

All right, I’m sold: there are lots of ethical issues here. Analyzing them, however, requires an open mind, at least at the outset.

O’Conner begins with the assumption that “the fragrance industry …trades largely in toxic chemicals that are known allergens and likely hormone disruptors.” Of course, the anti-chemical activists believe that virtually all chemicals are toxic. Almost anything can be an allergen to somebody, too. If one’s position is 1) anything that isn’t in place without mankind’s intervention is inherently suspect and dangerous and 2) chemicals are presumptively bad unless conclusively proven otherwise, then scenting the air is obviously unethical. This presumption of harm would have stopped human progress dead in its tracks in the 19th Century, and I know many of O’Connor’s compatriots would say that would have been better for everyone. A more rational approach is that strangling new ideas and technologies in their cribs is a dead-end strategy for society and civilization, and that innovation ought to be encouraged and given an opportunity to develop. If the chemicals are poison, then yes, spraying them all over the place is unethical. Beginning with the conclusion that chemicals are by definition poison, however, is unfair.

The relevant ethical problem is whether the scents should be used if some people will have serious or unpleasant allergic reactions to them—the peanut problem. Utilitarian ethical analysis of this issue reaches a different conclusion than other approaches. If conduct benefits thousands of people and helps businesses to thrive but will kill an unlucky few, a balancing calculation may still conclude that the conduct is ethical if due care is taken to minimize the harm, and the victims receive fair compensation for the rest of society. If conduct benefits thousands of people and helps businesses to thrive but will irritate an unlucky few, I have no problem concluding that the conduct is ethical, again as long as those who might be irritated are given appropriate consideration. I know this is far from the clear majority view, as society is increasingly seduced by a dictatorship of the aggrieved few.

If Abercrombie and Fitch, however, gives due warning that their stores are scented and people with allergies to perfume should stay away, the store is within ethical boundaries. (I would hold stores with strong natural odors to the same standards, as well as the Greek Orthodox Church. Potpourri and incense both make me want to vomit.) The practice of making perfumes so strong that they waft out into the street, an Abercrombie and Fitch tactic, is ethically troublesome….if the scent can trigger allergies. If not, I don’t see how a rational ethical argument can be constructed that holds an artificially engineered smell emanating from a retail store to be unethical, while the smell of baking bread leaking out of a small town bakery is one of the enduring joys of small town America. I think I know what O’Conner would say (“Natural=ethical; artificial=unethical”), but I think that is based on bias, not reason.

The second ethical objection to scent-branding in her essay is that “the chemicals used in fragrance are anything but environmentally safe.” That’s not an argument; it’s an assertion. What is the definition of “environmentally safe”? How does the scent in the Polynesian Village resort in Disney World do measurable environmental harm? We can’t apply a balancing standard without knowing the weight of what is being balanced.

Only at the very end of the article are the juicy ethical issues addressed, and O’Connor sums these up as “a slippery slope.” Let’s be specific where she wasn’t:

Honesty: Is using perfume to disguise reality unethical? Is it wrong to use odor to make something seem better than it is? I think society made this call in other areas long ago, and there is no justification for treating scent differently. We don’t regard make-up and cosmetics as unethical. We don’t regard the use of visual and aural stimulation to provoke affection and sexual arousal as wrong. We approve of the use of colors, furnishing, art and cultural symbolism to make offices and environments more pleasing and comfortable. Music has at least as powerful psychological effects as smell; nobody has suggested that having a string quartet playing in a restaurant is deceptive because diners will think their food tastes better.

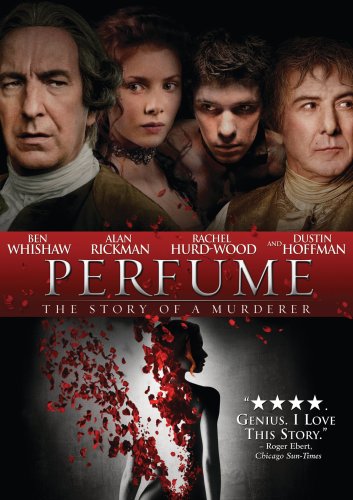

Autonomy: Is it ethical to use odors to trigger sub-conscious emotional and physiological reactions in unsuspecting people? The issue can’t be decided, as O’Connor would have it, by sliding to the bottom of the theoretical slippery slope and making the call there. The terrific, if creepy, novel “Perfume” by Patrick Suskind shows us scent-manipulation Hell, in which a serial killer with a genius for making perfumes devises a scent that makes everyone trust and adore him. Yes, that’s unethical; so was the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

Coercion and mind-control is unethical, but making people feel more comfortable in an environment is hardly that…unless, and this is a big unless, strong perfumes can fairly be defined as mind-altering drugs. If they are, then society needs to make some very difficult distinctions. Is a man-made stimulus that causes the body to release strong attitude-altering hormones (which are drugs) ethical, but a chemical that triggers the same response unethical? All right…but why? A woman uses scientific and experience based knowledge of male sexual response to dress and act in a way that maximizes the likelihood that it will stimulate an involuntary hormonal reaction in a targeted make producing lust and desire…that’s all right. If she uses a perfume that duplicates powerful pheromones, however, why is that cheating? We can, as a society, decide that it is; we can decide that gyms have to smell like dirty socks and sweat, and that vintage hotels have to smell like old cigars and decaying leather—call it “truth in stinking”—; we can also decide that sounds, sights, textures and symbols that influence our moods are just dust ducky, but making the local Christmas store smell of hot cocoa, roasting chestnuts, evergreen trees and Christmas morning using chemicals is sinister and manipulative. We can strangle the science of scent in its crib, to make sure it doesn’t grow up to be a monster.

I think scent branding is a complicated issue, and that we need more data, followed by some quality analysis and open-minded debate by people who don’t have an agenda. The concern expressed in the O’Connor article should mark the beginning of the inquiry, not its conclusion.

I agree this is a complicated issue. As you said, restaurant smells (natural, I assume) tend to make people hungry (or more hungry than they really are), as do waiters with large platters of beautiful food which often encourage patrons order more, different, and perhaps more expensive food than what they may have had in mind. The goal of the restaurant is to sell food: if memory serves, it’s only been in the last 20 years or so that restaurants had at least parts of their kitchens open to the dining area so “good smells” could waft out from them. My memory from childhood of elegant restaurants were the multiple green baize doors that completely closed the kitchen off from the dining room. So was this change intentional or simply simpler and cheaper as restaurant designs? I don’t know, but it’s different.

As Jack said, perfumes have been used for centuries… first to cover up body smell when bathing was less convenient than it was today. Powder and make-up, similarly, were used to cover unhealthy skin coloration and blemishes for which, at that time, there was no effective solution. Science and pharmaceuticals have made great progress in creating products that obviate the historic need for perfume and make-up. With these advances, however, came a massive cultural change: now one must NOT have a blemish, and even if one’s skin is perfect (I’m talking mostly women now, with a few male exceptions and people made up for movies and television) make-up is a normal addition to the human (or at least Western) presentation to the public. Perfume and cologne is an enhancement, not a way to cover up unpleasant body odors. Do many of these products contain “unnatural” and possibly “toxic” ingredients? You bet they do. Do they affect the behavior (or at least the attitudes) of those who come in contact with pretty men and women who smell good? They absolutely do, and not just in entertainment and news broadcasts. I would love to see the percentages of good-looking professionals on the way up vs. the perhaps more intelligent but uglier ones in the same company.

And the need (increasingly pronounced with every decade) to always always look younger than one really is adds an entirely new set of questions. But with all of these, it is an individual choice to use them or not. Unfortunately, some individuals don’t like perfumes and colognes and make-up, but just as it is an individual choice to use the product, so it seems to be (mostly) an individual choice not to be around those who use them if they bother you.

I am not one who automatically distrusts corporations, but creating scents on a mass basis to encourage spending does bother me. (My exception here would be Disney… which remains the most perfect capitalistic endeavor ever created — that provides entertainment, education, has advanced technology considerably, and abuses or denigrates practically no one.)

But IS the massive use of scent, which we knows affects behavior, unethical or a slippery slope toward unethical behavior? Because the Polynesian Village at Disney World smelled like, actually, Hawaiii (I’ve been to both), wasn’t tied to buying something, because any visitor had already paid to be there in the first place. Walt Disney was a genius and perfectionist, so it was a final touch to have your “village” actually smell like the real thing. The smell of the Polynesian Village (or any other on-campus named enclaves like the Grand Floridian) was a very small part of what encouraged visitors to spend money. It was mostly everything else… the amusements, the shows, the recreation, the food, etc.

But something about retail organizations using scent, and admitting outright that artificial scent encourages people to buy more, worries me, though I’m not completely sure how to explicate all the reasons. Except insofar that technology of all kinds is moving forward logarithmically, and today’s “simple” scent could soon be a complicated, breathable behavioral atmosphere that involves much more than scent.

I have to think this over. If this kind of unrequested behavioral modification product is in the corporate world, it surely has been looked at by government as well. Anyone remember “soma” from “Brave New World?”

I hadn’t made the “Brave New World’ connection, but it is apt. Your first “Comment of the Day,” on “Smell Sunday”!

My former adopted parents…and I may go missing for this post…engage in this form of mind control all the time. They begin loading my room with a heavy scent to make me believe I am being drugged. It is used to evoke a fight or flight response, to trigger a crisis so they have recourse to call ems or le. It is abuse in the cruelest form because discussion leads to accusations of paranoia because really, what loving parent would do such. Check out my writing and possible soon to be death, hospitalization, or abduction at sangrealta

2 examples:

1: Abercrombie and Fitch. I always hate that store because of the scent. As I walk by in the mall, the odor is so strong that it actually stings my nostrils. I think it’s fine if they want to Scent Brand, but to use so much of it that it stings the nostrils of someone passing by, I think will only result in more people gaining my conclusion: Stay away and don’t spend any money here.

2: Yankee Candle. Much like A&F, Yankee Candle often wafts into the mall from the entrance. But I don’t have as severe dislike for them because I think the smell is a natural byproduct of what they are selling. I may be wrong. Either way, the smell is still too strong for me to go in there and consider making a purchase.

Would it be unethical to spray a bunch of Febreeze at the entrance to A&F?

I like the Febreeze idea. It’s probably some form of unexplored trespassing, though.

If scent-branding is that offensive, you would think that the good ‘ol market system would solve the problem. People in low income housing might not have the same options.

I am unlucky enough to be affected by certain scents and chemicals. It’s not deadly allergies, just debilitating migraines. Despite this, I don’t have an issue with scent marking. I don’t see it as any different than modifying audio or visual stimuli.

If a store’s scents keep me away, that store loses business. So long as they are not intentionally driving away people with scent issues, I don’t see it as any different than having garish models in the window.

I think a more difficult question is individuals’ behavior in public places. A specific perfume on a plane can cause a migraine with no possible escape. How does ruining 2 days of my vacation (or making me completely ineffective during a business trip) balance against being more attractive to people you don’t know and likely won’t talk to?

To avoid some of the issues, many large companies have policies about wearing scents, but not everyone follows them. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had to walk out of a meeting because someone thinks their cologne is special.

My mother has anaphylaxis reactions to the vast majority of artificial fragrances, including all perfumes, some colognes, and most hair care products and body lotions. Walking past Ambercrombie and Finch (for example), her throat begins to swell shut. She carries an epinephrine pen and she has had to use it on multiple occasions. So, yes, there are allergic reactions to these products, and they are similar in severity to peanut allergies.

The unethical part comes in here: none of the fragrance companies will reveal their ingredients. Independent laboratory tests have shown that many fragrance blends contain hormone disruptors, carcinogens, teratogens, et cetera. My mother wanted to pinpoint the specific chemicals that trigger her worst allergies, but no companies would reveal the ingredients, even though her allergist wrote several letters explaining the medical necessity of disclosing the ingredients.

Pumping chemicals in the air probably can’t be considered ethical or unethical, any more than me snacking on a package of peanuts is unethical. But refusing to disclose the chemicals in your products, especially when they are known or suspected hormone disruptors or carcinogens is completely unethical. Refusing to disclose chemical ingredients to the patient who had to visit the emergency room because she was exposed to your product is completely unethical.

Can I up some of those actions from unethical to evil?

It should be illegal to pump chemicals into public airspace! I have chemically-induced asthma and other allergic reactions to many fragrances and I almost cannot even go to the mall, especially near Abercrombie & Fitch. How dare they presume that anyone walking near their store would like or not react to their horrible chemicals! Why the mall allows this infraction into the public airspace is beyond me. The churches are doing it and workplace buildings the same. While many state governments and countries (Canada) are banning scents from the workplace due to illness, you have THIS being introduced. How unbelievably insane! I will go to my state representatives to convince them and work with them to get “ambient scenting” outlawed.